El Cuhamil: Documenting the Farmworker’s Demands for Justice

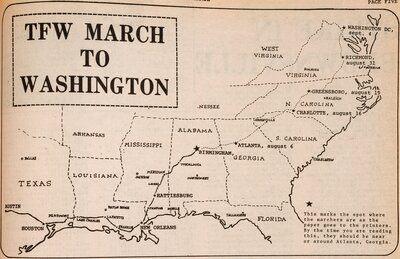

One of the most commemorated marches of the TFWU was the historic 82-day, 1,500-mile, March for Human Rights. The marchers, consisting of a group of 42 members of the TFWU and their children, left Austin on June 18, 1977, and walked across the US South through 8 “right to work” states. Both literally and symbolically, marchers linked the struggles of rural workers across the South of the United States. And, in so doing, they made connections between the anti-black violence that impacted Black farmers in the US South and the increasing xenophobia and racism Mexican and Mexican American farmworkers faced in South Texas.

El Cuhamil documented this interstate march among a multitude of other voices that participated in the Texas farmworker movement in the 1970s.[1] As the official bilingual newspaper of the Texas Farm Workers Union (TFWU), its first run began soon after the founding of the organization in 1975 in San Juan, Texas, continuing through 1982 when the TFWU dissolved. It ran frequent articles on issues impacting farmworkers directly and information pieces on union representation. The newspaper also published human interest pieces on international worker solidarity, the rights of undocumented workers, and other stories that reflected a diversity of battles by poor and working-class people against capital interests. This section will explore the Texas farm worker labor organizing in the 1970s through El Cuhamil.

The significance of El Cuhamil to farm workers is clear, as can be seen in Luis Guerra’s Texas Farmworker March for Human Rights poster titled “¡Hasta La Gloria!”. As a voice of Texas farm workers, the publication played an important role in reframing the exceptional violence from and against them as they organized. Nahuatl for “a strip of undesirable land”, El Cuhamil was named after a small piece of land the Catholic Church donated to farm workers following the Starr County Strike in 1966.[2] Through its name, the publication and the TFWU linked their origins to this event.

Beginning in the 1960s, farmworkers began to organize their labor. The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 secured workers' right to collective bargaining and provided protections from retaliation, but excluded most agricultural workers from these protections.[3] This meant that farm workers faced monumental challenges in organizing and had little or no protection from the vicious attempts by growers to suppress unionization efforts. This was clear in the deployment of white supremacist violence against Starr County strikers in 1966, including beatings, harassment, and threats of lethal violence. These aggressive strike-breaking tactics became part of a broader pattern of violence and repression by growers backed by sympathetic courts, law enforcement, and media.[4] The TFWU documented such instances of violence through El Cuhamil and connected them to each other to reveal their systemic nature and reclaim the narrative in the public eye.

The newspaper also served as an educational tool. Recurring articles disseminated information explaining the legal protections unions provide and offered practical guidance for workers facing violations of these protections. The newspaper also educated readers on the impact of “right to work” laws on farm workers and the legislative campaigns the union was fighting for. The focus on educational content reflects the centrality of education in the farmworker's fight for justice.

The influence of Chicano art and literature and the quasi-nationalism of the Raza Unida Party are seen throughout El Cuhamil. However, these influences are juxtaposed by broader calls for solidarity with poor and working-class people across racial, national, and cultural lines. For example, the newspaper frequently and fervently advocated for an internationalist approach to organizing labor that understood Mexican workers as part of the same system of capitalist exploitation.

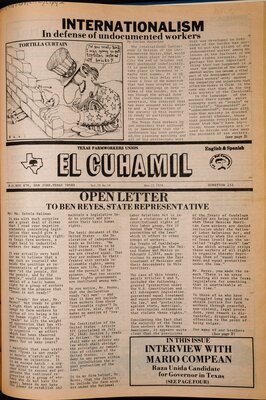

Contributors to the newspaper often used cartoons to demonstrate how broader capitalist and imperialist systems impacted all workers. For instance, in this 1978 issue, a cartoonist depicts an oversized Jimmy Carter building a wall over the body of a Mexican worker. They emphasized the structural violence of the border and how it benefits the capitalist class. Together, such contributions demonstrate the nuanced critique of the Southwestern political economy that undergirded the farmworkers struggle for the right to organize their labor.

footnotes:

[1] Virginia Marie Raymond, “Mexican Americans Write towards Justice in Texas, 1973-1982, ” (Dissertation, 2007), vi.

[2] Raymond, 388.

[3] National Labor Relations Board, “National Labor Relations Act,” National Labor Relations Board, 2022, https://www.nlrb.gov/guidance/key-reference-materials/national-labor-relations-act.