Lines of Communication

With every reform he introduced, Gálvez faced a significant obstacle: the limits of colonial communication methods. All at once, he was acting on instructions from the monarch, replying with his own suggestions, sending inquiries to community officials, and working with the local authority figures to implement changes. Each correspondence required weeks, if not months, of waiting, as the letters traversed oceans, mountains, and deserts. In order for the Visitador’s reforms to take effect, he had to work in conjunction with the local bureaucracies. They would need full instructions, as well as the opportunity to submit questions or complaints.

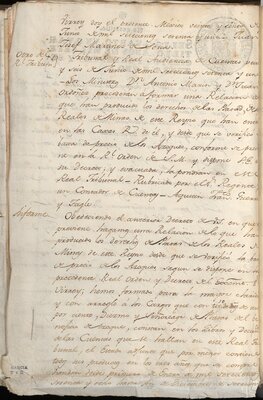

Discussions about the silver and mercury industries in the early 1770s illustrate the complexities of communication during this period. On August 31, the Viceroy sent a letter to the king about the production levels of each substance from January through August of 1770 (under the margin ‘Testimonio de Real Orden' in this document). The monarch finally received it in January of 1771. In response, he ordered the authorities in New Spain to send him a report of the production profits.

The monarch’s response took six months to arrive back to New Spain. Under the margin ‘Decreto del Exmo. Sr. Virrey' in this document, the Viceroy noted a date of receipt of June 21, 1771. In a few days, on June 25th, he ordered his assistants to pass it onto the Tribunal de Cuentas, or the Ministry of Accounting. Its officials would be the ones to create a financial report.

The Tribunal de Cuentas was located in the same city as the Viceroy (Mexico City), so the document arrived there the following day, the 26th, as indicated under the ‘Otro del Rl. Tribunal' section in this highlighted record. On that day, its ministers noted that they would comply with the request to create a financial report. The Tribunal ministers finished their report by September 3rd as noted under the ‘Informe' section in this document. Antonio del Campo Marin and Juan Ordoñez de Seixas, the two main accountants, signed the document.

All of these correspondence records would have been useful resources for Gálvez, as he worked to increase efficiency of mining and other industries of New Spain. Both the time required for cross-Atlantic communication and the number of people involved in these conversations complicated his task. However, it made the cooperation between him and local government agencies essential.