Becoming Eric Williams

Eric Williams was born on September 25, 1911 in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, to Thomas Henry Williams and Eliza Frances Boissiere. He was the eldest of twelve children. Pictured above: Henry Williams, Eliza Frances Boissiere Williams and their children. Eric Williams stands third from the left.

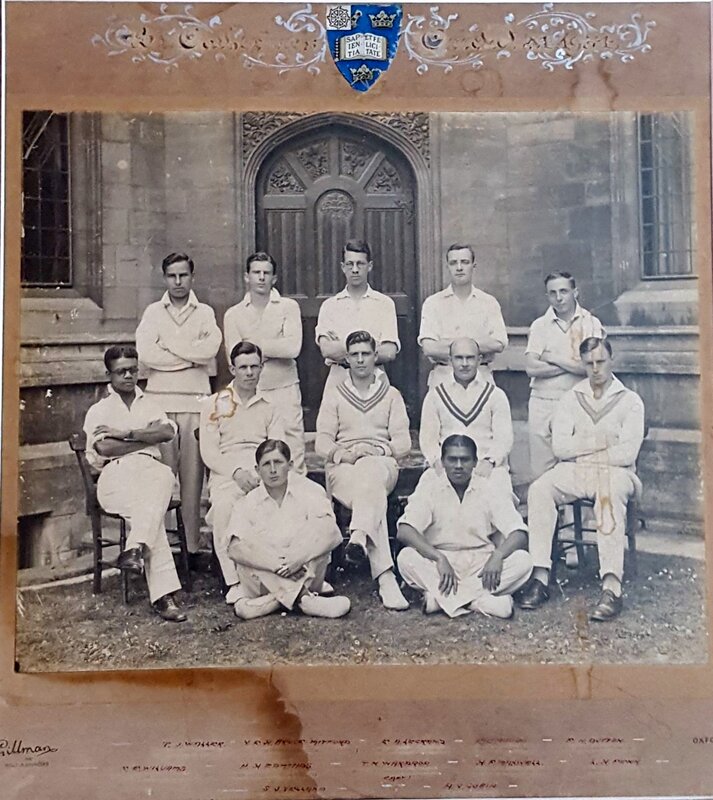

As a young student, Williams attended high school at Queen's Royal College in Trinidad. In 1931, on his third and final try, he received the prestigious Island Scholarship to Oxford University in the United Kingdom. While there, he played on the cricket team.

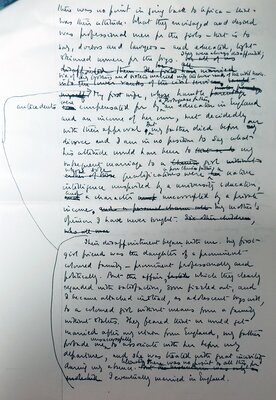

“[My father’s] wish was that I should study medicine or law, preferably the former. He wanted me to have 'independence,' as he put it. From a very early age, my view diverged from his. I was determined to be a teacher...He was accordingly very angry with me. He protested and remonstrated, argued and sneered, cajoled and persuaded. It was all in vain; I had made up my mind. He gave in with poor grace. When I saw him in 1944, after twelve years, having got not only the bachelor's degree but the doctorate in philosophy, he greeted me with: 'So you are a doctor after all!'”

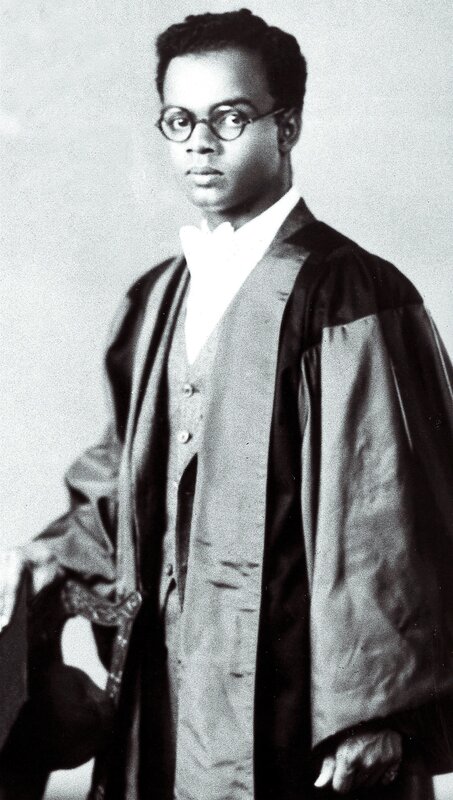

Williams placed first with a First Class Honors degree in Modern History in 1935. He went on to earn his doctorate from Oxford in 1938. His doctoral thesis, The Economic Aspect of the Abolition of the West Indian Slave Trade and Slavery, would later be published as Capitalism and Slavery. After completing his studies at Oxford, Williams joined the faculty of Howard University in Washington, D.C. In Capitalism and Slavery Fifty Years Later: Eric Eustace Williams – A Reassessment of the Man and His Work (2000), historian John Hope Franklin recalls:

“When Eric Williams, fresh from Oxford University, where he earned a Double First in the Honor School of Modern History and a D. Phil. degree, arrived in the United States in 1939, he was most enthusiastic about his new position at Howard University. He had received an appointment as an assistant professor of political and social science, with the special responsibility of planning and teaching a social science introductory course that was compulsory for all freshmen students. This was, he felt, a wonderful way to begin his career at the "Negro Oxford", as he was to dub Howard University...he was able to introduce new and exciting materials that could not be found in similar introductory courses elsewhere and to make the course more attractive to students by including materials and topics in which they would have a special interest, not excluding sex and race. This would be one of the most important contributions that Williams made to the intellectual and educational life of Howard University, for it touched many hundreds of students while it set an example to his colleagues of how it was possible to be creative at an institution that was, in so many ways, stultifying to the creative impulse. His big survey course in the social sciences was a great success, and he was popular with his students who usually surrounded him asking questions following each meeting of the class.”

In 1943, Williams organized "The Economic Future of the Caribbean'' conference, which brought together an international group of scholars, diplomats, and the top leaders of the Anglo-American Caribbean Commission to Howard University to discuss the important issues of the region. This conference led to Williams' appointment as a consultant to the Commission. The Commission was founded in 1942 to oversee the impact of World War II on the Caribbean, and improve the economic and social conditions of the region. The conference proceedings were published as The Economic Future of the Caribbean, edited by Eric Williams and E. Franklin Frazier.

In 1948, Williams assumed leadership of the Research Branch of the Caribbean Commission in Trinidad and Tobago. He stepped down from his position at Howard University, and in 1955, began delivering public lectures in Woodford Square, a plaza in the center of Port of Spain. During these popular speeches, Williams would address important political, educational, and social issues of Trinidad and Tobago. Williams would deliver over 150 lectures at what he re-named the “University” of Woodford Square to crowds as large as 20,000 people. During this time, Williams also delivered speeches in Guyana, France, United Kingdom, Jamaica, Barbados and Grenada.

Sir Norman Costar, the first British High Commissioner in Trinidad and Tobago, was an outspoken opponent of the “University,” declaring that Williams’ “public outbursts in Woodford Square arouse interest as theatrical performances. There is no live theatre in Port of Spain and Dr. Williams’ speeches are rated high as entertainment, by those for whose benefit they are uttered.” He was not alone, as British official R. L. Baxter proclaimed the Chief Minister’s speeches to be “a queer mixture of scholarly exposition and demagogic invective, ending with a parody of the New Testament that smells unpleasantly of Africa.”

To that, Williams countered:

“The “University” of Woodford Square is a centre of free university education for the masses, of political analysis and training in self government, for parallels of which we must go back to the city state of ancient Athens. The lectures have been university dishes served with political sauce. They have given the people of Trinidad and Tobago a vision and a perspective...they have reinforced their own aspirations…for human freedom and for colonial emancipation. They have taught the people what one French writer of the 18th century saw as the greatest danger, that they have a mind.”

Eric Williams Inward Hunger: The Education of a Prime Minister (1969), pg. 133

"To someone like myself, who was a teenager in Trinidad when Eric Williams burst onto the public scene there around 1955, certain of these pieces have an emotional power far beyond their considerable force as political analysis and argument. Single-handedly and single-mindedly, Eric Williams transformed our lives. He swept away the old and inaugurated the new. He made us proud to be who we were, and optimistic, as never before, about what we were going to be, or could be.”

Arnold Rampersad, Sara Hart Kimball Professor in the Humanities, Stanford University

In 1951, Eric Williams married his second wife Evelyn Soy Moyou (1924-1953), whom he considered the love of his life. Pictured below: Eric Williams's daughter, Erica Williams Connell (left), and Evelyn Soy Moyou (right).

In a draft of his autobiography, Inward Hunger: The Education of a Prime Minister, Williams writes of Moyou: “She had a native intelligence, unspoiled by a university education.”

In one note to Moyou, Williams wrote:

“…we may be apart physically but we are together spiritually, and writing to you symbolizes this… I have been feeling so morose that I have not even wished to play my records. Curious that what used to be my only companions, the very essence of my aloneness, have now become a part of our kinship, which I cannot play when you are not with me...”

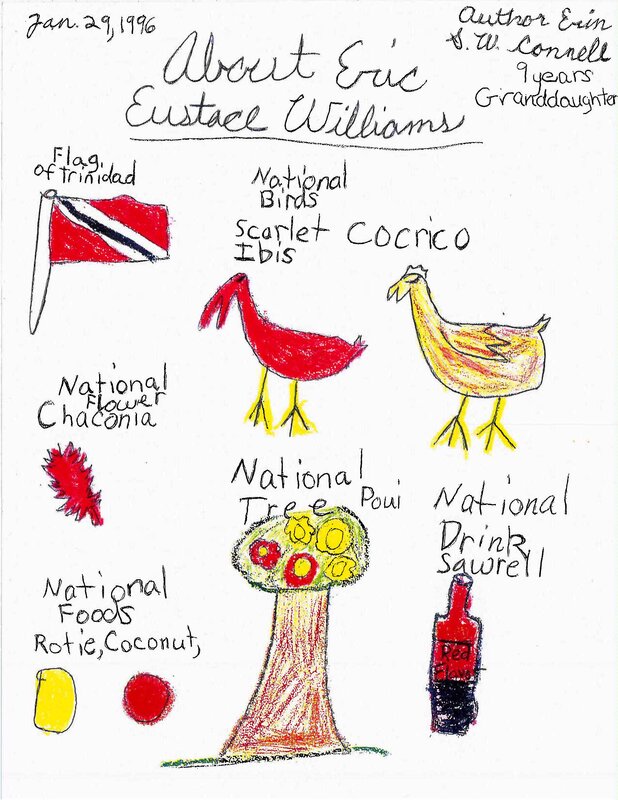

Eric Williams and Soy Moyou’s daughter, Erica Williams Connell, would go on to become the founding curator of the Eric Williams Memorial Collection Research Library, Archives & Museum at The University of the West Indies, Trinidad and Tobago.