From Democracy to Reform

Federal troops and rural Mexican children on train tracks, circa 1914–1919.

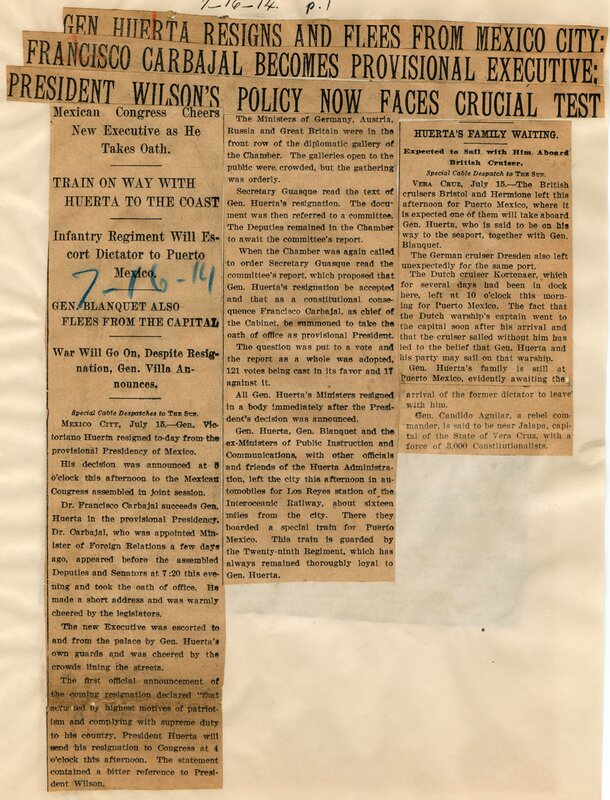

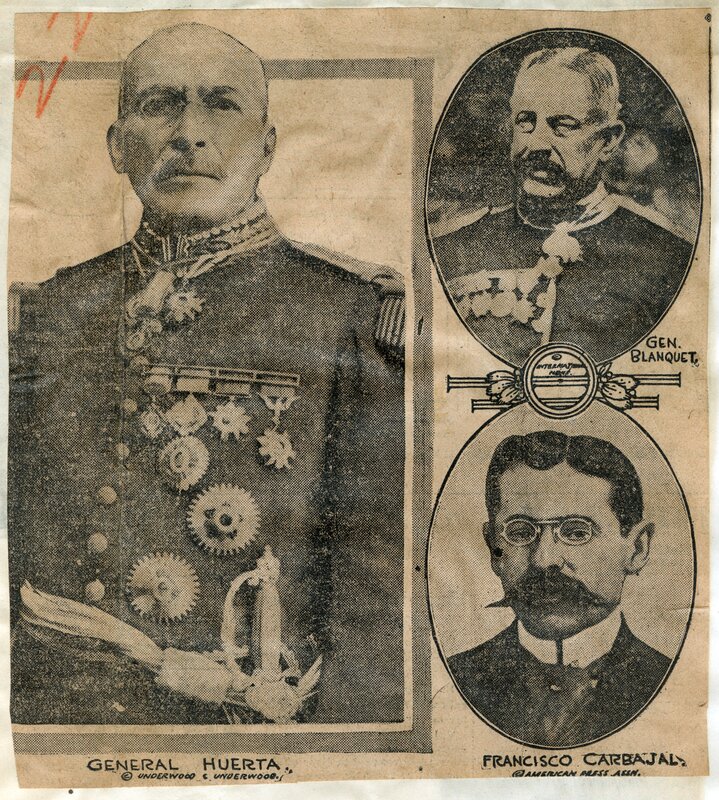

Huerta’s Downfall

Railroads, which directly connected the north to Mexico City, were key for the Constitutionalist army. With the U.S. legally furnishing firearms, the Constitutionalist army soon became the formidable force needed to go against Huerta’s army. The rebel army started its coordinated attack in the spring of 1914. Alvaro Obregon led his Sonoran division along the Pacific coast, while Francisco “Pancho” Villa’s Chihuahuan force marched through central northern Mexico. From April through June 1914, the Constitutionalist army drove Huerta’s forces southward as it overtook Torreon, Zacatecas, and other northern strongholds. Surrounded by the fast approaching northern offensive, Zapata’s south-central army, and loosely-allied local rebels, Huerta resigned and fled on July 17, 1914.

Reform

Unlike Madero, the incoming leadership prioritized land and labor reform over democratization in its legislation. The redistribution of land varied between regions: Villa delayed the reform given his dependency on the agricultural production of large estates to maintain his northern army. Zapata, on the other hand, moved swiftly to reallocate lands among the agrarian class in central Mexico. Industrial workers also obtained rights, including a minimum wage and union organization, through the incoming government’s laws.

Revolution 4.0

The convention ended with two factions at war: the Carrancistas versus a Villista-Zapatista bloc. Their envisioned approach to government differed: Carranza pushed for a strong central federal government while Villa seemed okay with the opposite. In the first half of 1915, both sides battled for power throughout central Mexico, north of the capital. In the end, Obregon outsmarted Villa in the battlefield, handing Carranza the victory at the end of summer 1915. By October, the U.S. recognized Carranza as provisional President of Mexico.

Although Alvaro Obregon had significantly repressed the Villista-Zapatista bloc, Venustiano Carranza’s opposition continued to fight. Reduced to guerilla warfare and resenting the diplomatic recognition, Francisco “Pancho” Villa retaliated against the U.S. through a series of attacks along the border, including the infamous March 1916 raid of Columbus, New Mexico. The U.S. sent an expedition into Mexico to capture him, which failed and ended in early 1917. The Zapatistas also continued their guerilla warfare in Morelos. Meanwhile, Félix Díaz and his Felicista forces, which represented the conservative faction of the political spectrum, countered the Carrancista government in the south.

Carranza’s Government

Just as Diaz, Madero, and Huerta had done, Carranza relied on force to suppress dissent. After Huerta’s ouster, he abolished the federal army, closed the courts, and suspended constitutional rights in August 1914. He also forcefully disbanded a general labor strike in August 1916 that emerged as a result of hyperinflation. Once he was provisional president, his government controlled the press and politically sidelined revolutionaries who had not supported him. As a result, Carrancista middle-class politicians controlled all states but Chihuahua and Morelos by the fall of 1916.

Constitution of 1917

To validate his administration, he convened a congress to create a constitution in November 1916. Carrancistas from all over the country came to Queretaro to draft the document. While Carranza hoped to mostly replicate Mexico’s 1857 liberal constitution, the majority, including his general Obregon, wanted to include radical provisions. The Carrancistas encoded in the 1917 constitution measures that favored laborers and kept the Catholic Church out of politics and primary education. Most importantly, they gave the government the right to nationalize private property, primarily foreign-owned lands, for land redistribution.

Democracy Prevails (Eventually)

With the Constitution in hand, Carranza was finally able to establish a legitimate government. He administered elections in March 1917 for Congress and the presidency, which he predictably won. Even though the newly formed Congress only contained Carrancistas, different factions emerged among the elected officials, not always in line with the president. The various priorities soon slowed down progress on the social and land reforms the Carrancistas had demanded in the 1917 Constitution. Despite this, the laborer and agrarian class now had a new tool to meet their demands: a democratic government they could influence with politicking and votes.