Conservative Pushback

The Mexican Revolution saw multiple presidencies in quick succession. Over the course of ten years, four different men assumed office, each time setting off a new wave of revolution throughout the country. While Mexico City saw the multiple presidents go in and out of its national palace, it was mostly immune to the violence that came along with each transition. Rather, Mexico City was a hub for political power, the gathering place for presidents, diplomats, and ambassadors. Additionally, this is where a lot of the press was coming from, informing the public opinion of the revolution.

Decena Trágica

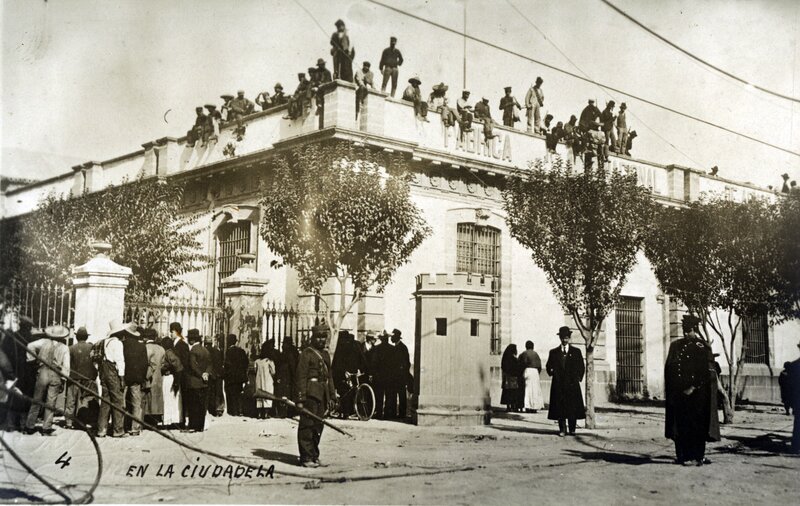

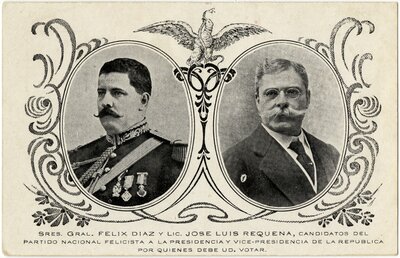

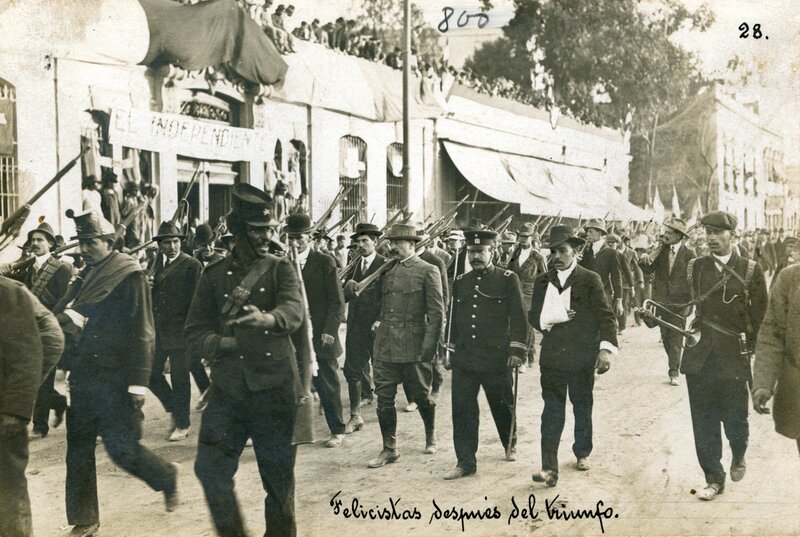

The capital would eventually experience first hand the war that ravaged the rest of the country on February 9th, 1913 when Mexico’s conservative elite and military pushed back against Madero’s revolution. Within “Ten Tragic Days” (or Decena Trágica, as the event would be called), three army generals led a coup against President Francisco I. Madero. Generals Bernardo Reyes and Felix Díaz, nephew of Porfirio Díaz, broke out of prison in Mexico City and marched into the capital with their army intending to overthrow President Madero. After soldiers killed Reyes, Díaz’s rebels, or Felicistas, occupied the city’s citadel for the next ten days. During this time, mass destruction and violence overtook the city until the rebels successfully usurped the presidency from Madero.

Tenuous Relationships

This event is a small-scale representation of the Mexican Revolution at large. Different groups simultaneously vying for power with particular agendas. Though there were often two sides fighting against one another– the government versus the revolutionaries – there were divisions within. Tenuous relationships between factions would form, dissolving once their goal was completed. This was the case when General Victoriano Huerta, leader of the government forces, joined rebel Felix Díaz to overthrow Madero. After their victory, Huerta took over the presidency until a general election in October, when he was supposed to support F. Díaz’s candidacy for office. Instead, General Huerta double-crossed F. Díaz, and became Mexico’s next dictator.

Through Multiple Eyes

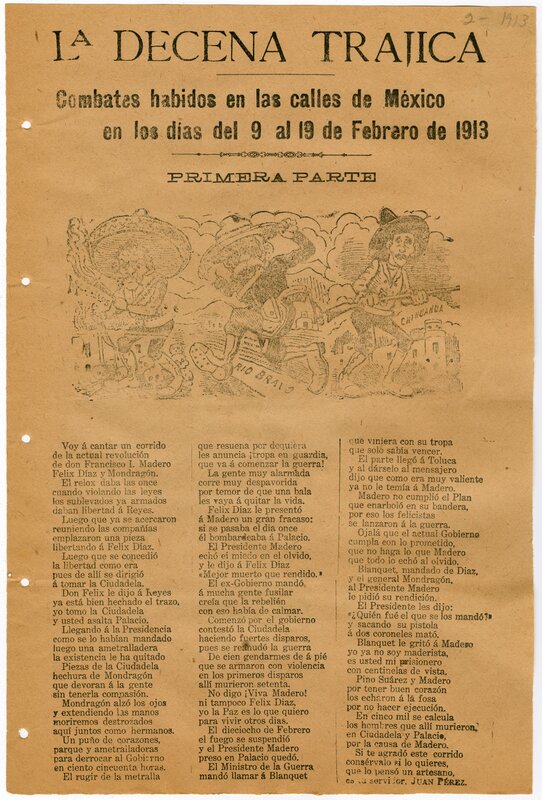

Popular culture and folklore provide insight on the terror civilians felt during the coup. A corrido by Juan Pérez, an artisan, contains day-by-day narration of the event, focusing on the plight of the capital’s residents. Pérez writes, “I don't say ¡Live Madero! Nor do I say Félix Díaz, all I want is Peace so I can live more days”. He describes the terror that people lived during this time, saying that they would run for their lives in fear of the bullets raining from the buildings. The ballad captures the fear and the loss experienced by the people of Mexico City, instead of focusing on the political motivations behind the attack.

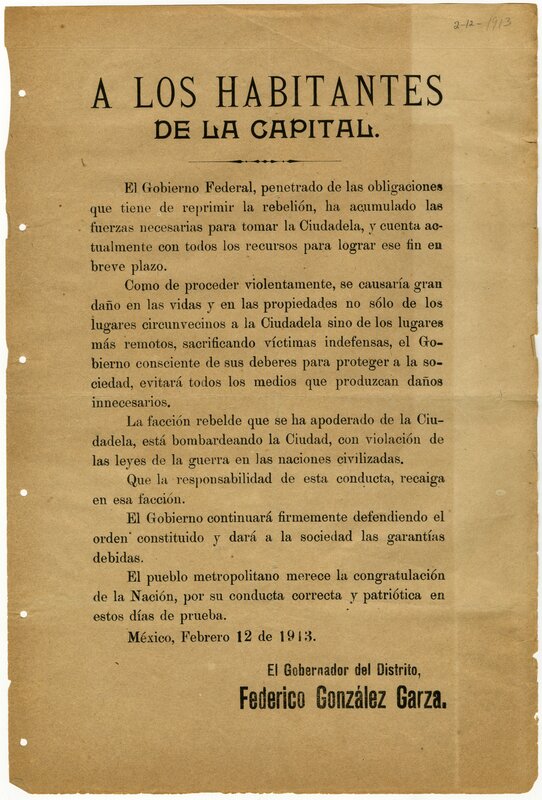

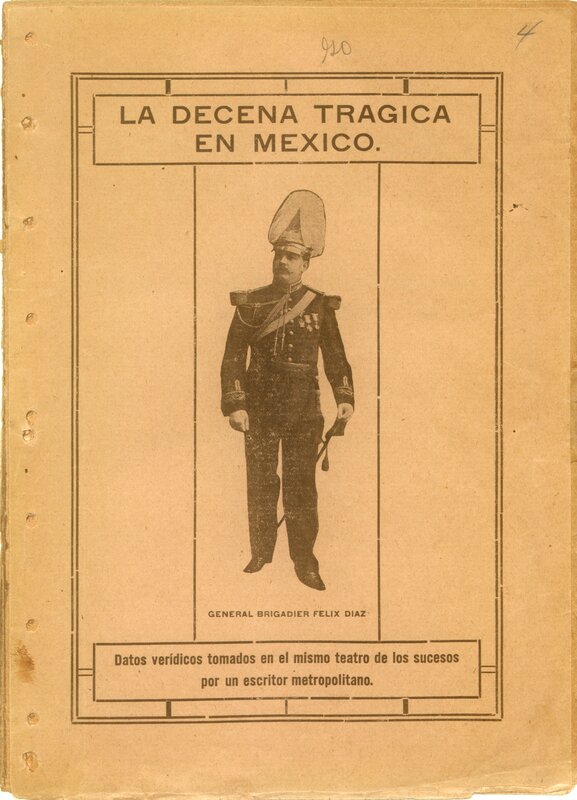

Other accounts provide a more in-depth journalistic description of the Decena Trágica. Such is the case with this brochure published in 1913. A particular passage highlights the horror of seeing the burning of the deceased on the streets. There is little commentary and the narrative is mostly focused on facts and observations. The author makes sure to say that he is relying on the most recent information “from people that were directly or indirectly part of the events”. The brochure reads like a mostly unbiased unfolding of events meant to summarize and document the Decena Trágica.

Although it frames itself as an unbiased source, this piece counters the ballad’s perspective suggesting an anti-Maderismo stance. The author criticizes Madero’s response to the coup, stating that while everyone else worried, Madero dismissed it by smiling and saying that “it’s nothing”. He also disparages his tenure as a president, describing it as a compromise to the “future of the Republic with their mistakes”. It is clear that the author had no faith in Madero, and let some of that sentiment shine through his work.

Some people had the privilege to observe the events without much fear for their lives because of their social position. Such was the case with Graham Kerr, an American journalist living in Mexico City. In a letter to his wife, he describes the Decena Trágica, often focusing on the artillery, mentioning the “boom, boom, boom, crack, rattle, boom, rattle, rattle, boom crack, rattle“ of the rifles and saying that it was a “stupendous waste of ammunition”. While there are some mentions of the violence against people – a washerwoman hanging clothes on the roof of his hotel and two casualties on the street – it’s always done in passing. Rather, he describes this as an event he “greatly enjoyed and would not have missed it for anything”.

Americans enjoyed certain protection since revolutionaries did not want to upset the United States and jeopardize their political ties. This allowed Kerr and other Americans to view the tragedy almost as a spectacle, knowing that they were in less danger. Additionally, their stay was temporary and they had no real stakes in the aftermath of the violence. This meant that foreigners could write a sensationalized, almost detached, version of the Mexican Revolution.