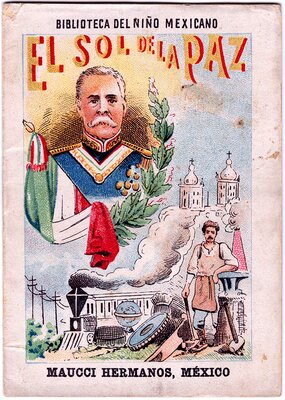

Porfirian "Peace"

Political cartoon depicting the Sun of Peace, Porfirio Díaz, looking over the exploitation of Mexico’s people for the benefit of Europe’s elite, 1908.

After decades of political turmoil, the stability Porfirio Díaz established from 1876 onward allowed him to maintain a dictatorship. During his decades-long rule, Mexico’s economy flourished through the attraction of foreign investment that primarily exported resources to the U.S. and Europe. These included mineral and agricultural goods. To facilitate this extraction, Diaz funneled government spending and investment to building Mexico’s infrastructure: railroad, telegraph, and ports. Railways were the most impactful investment, connecting the capital city to Veracruz and the United States.

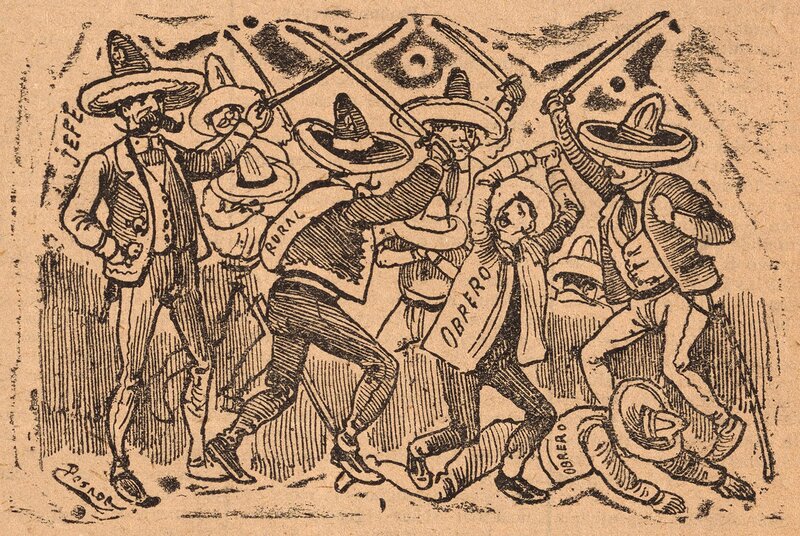

Dependency on foreign investment for national development, specifically on agriculture, negatively impacted rural society, which comprised more than three-quarters of the population. A state-of-the-art army and local police forces, or rurales, effectively repressed any urban and rural grumblings. These were under the control of politically-unopposed Porfirian governors and local political bosses. The Diaz government increasingly filled these posts with members from regional oligarchies who were unsympathetic to working class woes, extracting taxes and implementing oppressive social controls. Although they complied with Diaz’s centralization of the government, regional and local oligarchies in the north resented the capital’s authority over them.

The Porfirian government’s violent repression of worker strikes in Sonora and Puebla communicated to most Mexicans that its role was to protect American and oligarchic economic interests. In the agrarian sector, railways greatly facilitated the exportation of agricultural products. Seeking a cut of the profit-boom, large landowners appropriated “vacant” communal lands and exploited the rural class through low wages and peonage to satiate external demands. Thus, landowning farmers became tenants that contributed to the profit margins of regional oligarchs.

The Anti-Reelection Movement

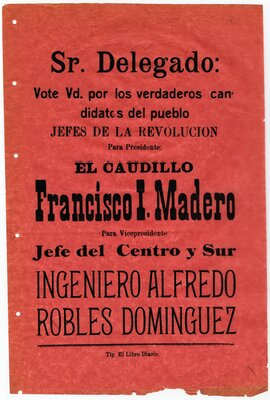

The elderly Diaz started to lose his influence on distant oligarchs and his grasp of power in Mexico City as younger Porfirian politicians set their eyes on his eventual descent. In an attempt to legitimize his rule, Diaz instituted sham elections in 1900 and 1904 that predictably declared him as the winning candidate. However, the story was different in the 1910 elections when a broad anti-reelection movement sprouted throughout Mexico’s cities.

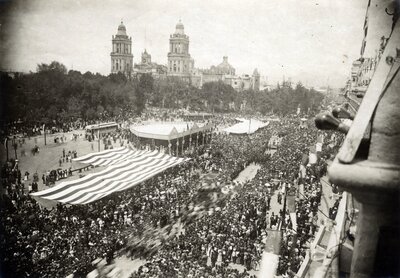

Spearheaded by the middle-class, the political opposition wanted to fully realize the aspirations of the 1857 liberal Mexican constitution. The working class, long exploited by foreign interests, subscribed to the movement’s patriotic and liberal message the penny press depicted. Francisco Madero, a northern idealist elite, soon became the leader of the newly formed Anti-reelectionist Party, leading a popular campaign across Mexico. Sensing an impending defeat, the Porfirian machine stifled the opposition, jailed Madero, and “re-elected” Diaz in June 1910, just in time to prepare for the country’s independence centennial celebrations.

Explore over 1,000 photographs of the Mexico's 1910 independence centennial celebrations below or through this ArcGIS Story Map.

Fighting with Words

Mexico City’s influential press provided a space for women to break through social boundaries. Juana B. Gutiérrez de Mendoza published Vésper and El Desmonte from Mexico City, using her platform to disavow Porfirio Díaz, advocate for Madero, and warn against tyranny. Other women worked behind the scenes to fight in the revolution. When Victoriano Huerta took control of the presidency in 1913, he targeted the press to control anti-Huerta movements, which made presses hesitant to print anything of the sort. That same year, Senator Belisario Domínguez found María Hernández Zarco, the only person willing to print his speech calling Huerta a tyrant. Mexico City’s presses, although separated from the revolutionary action, still had major implications on the war both politically and socially.