Construction

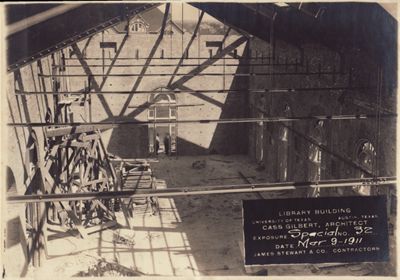

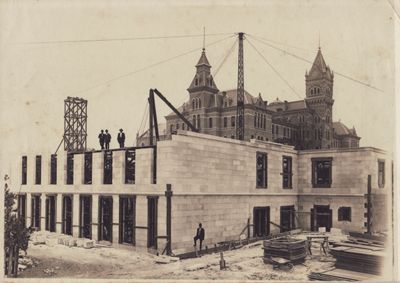

In Fall 1910, James Stewart & Company of Houston was hired by the University as the general contractor with Mr. S.N. Mapes supervising construction (Daily Texan, November 27, 1910). James Stewart & Company was a nationwide contracting company founded in 1845 that built banks, department stores, hotels and civic structures across the country. The firm was in business for over one hundred years and often took pictures of work for benefit of clients and architects. Gilbert, however, required his own photos in his specifications. The James Stewart Construction Collection is held at the National Building Museum.

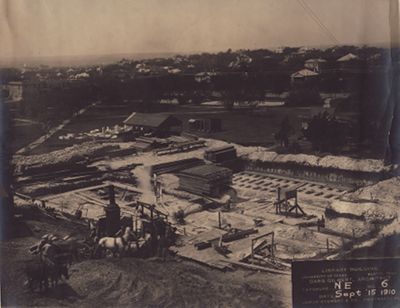

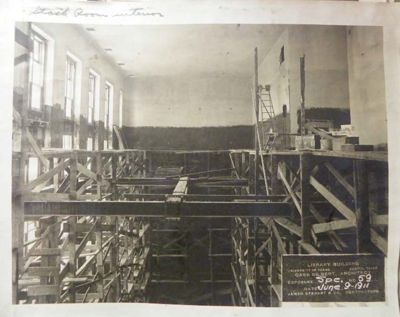

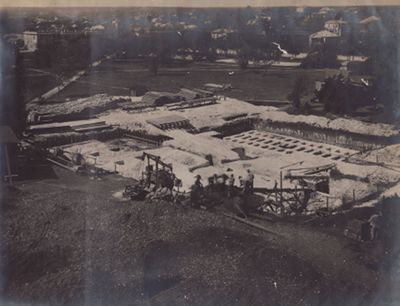

In April, site preparation started. Below are excerpts of letters from Cass Gilbert to James Stewart and Co. during the original construction of Battle Hall. They depict the strain involved in managing a project from great distances. By November the cornerstone was laid at a Masonic ceremony with Governor Campbell presiding. Less than a year later, the building opens in August of 1911, albeit without bookstacks, elevator, furnishings or electricity, all of which came the following year.

Correspondence from Cass Gilbert to Contractor James Stewart & Co.

September 6, 1910

I note that your teamsters who are hauling the gravel and send to the new Library Building are again trespassing into the roadway to the east of the building and as it is desired that this road be kept open for the full width, I would request that you have the material now covering one-half of the road moved up on the pile. Kindly give this your attention.

I note that in locating the boiler for the concrete mixer on the east side of the building that you have placed it too close to the building to allow it to remain here after the stonework has been started owing to the damage that will result to the stonework from the smoke and fumes from the boiler.

October 14, 1910

Following the telephone talk we had this morning, I wish to confirm my statement that the progress—or rather lack of progress—on the Library Building up to date is most unsatisfactory.

In figuring the values of work done to Oct 1, I find about 8% of the work done, and about 23% of the time elapsed. This is BAD. It is almost altogether owing to your failure to supply material and equipment. At this writing, not a derrick or hoisting engine is on the ground. The stone could some of it be setting if apparatus were here to handle it with. There would also be reason to talk with the stone man about progress if it were he and not you who was behind. About a month ago I warned you about getting equipment on the building, and even that should be unnecessary. It usually is the first thing to be thought of—to provide proper equipment.

Now you—not I—are the contractor on this work, and you are expected to take care of these details. That is part of your duty. I ought not be obliged to give this any consideration. Equipment and materials should have been here when needed. Promises to send them, or statements that they have been shipped from somewhere are not a satisfactory substitute. Imaginary derricks set no steel.

I have had just enough of being held responsible by others for delay by Contractors. The Portland Building which you recently handled through the Western branch is an example. The fact that the Contractor is responsible does no good if the Owner is convinced that I should have put the Contractor off the job and had it done by someone else. The influence on the owner of such an impression is most injurious to me, even though untrue. I am not going to stand anything of that sort on this building. You and I will get on well so long as your work is well done and up to time as to progress. When this changes, you will hear from me, and to the extent that seems to be necessary to GET THE BUILDING.

Now it is up to you to bring the percentage of completion up to the percentage of time elapsed, and keep it there. I certainly hope it will not be necessary to do more than to say this, but if it is, I am going to do it. If your Houston branch is too busy to care for this properly, get some more competent men. Effect an organization. If you have enough men, wake them up. Because this is a small job for you, I cannot have it neglected.

Respectfully,

Cass Gilbert, Architect

And a lack of construction: The 1920s proposed expansion

During his tenure as University Architect, Cass Gilbert created several general plans for the campus, but poor finances, as well as problems brought on by World War I, allowed the completion of only two of his buildings—the University Library and Education Building—now known as Battle and Sutton Halls. Mounting political pressure by local architects and others who thought UT should hire someone within the state of Texas pushed the Board of Regents to reluctantly end Gilbert’s association with the University in 1922.

The same year, the regents awarded a ten-year contract to Herbert M. Greene of Dallas as University architect. Greene was highly respected as a building designer, but it was soon discovered that his experience in campus planning was limited.

The following year, University of Illinois architecture professor, James White was recruited as consulting architect, and Robert Leon White, a UT architecture graduate in Austin (and no relation to James White), was secured as supervising architect. It was intended that James White would create a campus master plan, Herbert Greene would design the specific buildings, and Robert Leon White would oversee the construction in Austin.

James White submitted his first campus master plan for the University in fall of 1924. Eager to take advantage of the gently sloping hill that extended east into the new campus, White changed the orientation of the University from south to east. Buildings were arranged in a series of concentric rings spreading outward from the hilltop.

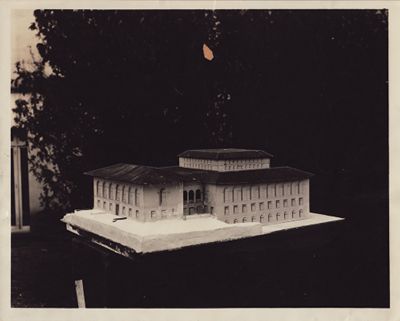

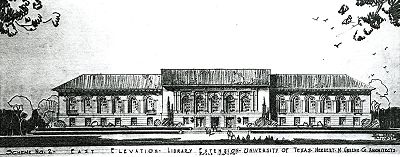

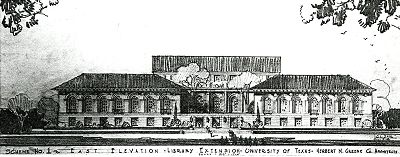

White envisioned the University Library (Battle Hall) as the focus of the campus, removed the Old Main Building entirely, and replaced it with a large square plaza. The library was to be enlarged so that its facade was roughly three times the length of the original building, and would be centered on the plaza’s west side.

Surprisingly, the Faculty Building Committee, the University President and the Board of Regents all approved this radical new design. But within a year, the regents reconsidered and rescinded their decision, though by then, the Library Building had become the top priority. It was too small to support the University’s 300,000 volumes. The building had to be expanded or new facilities constructed.

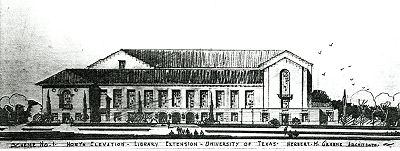

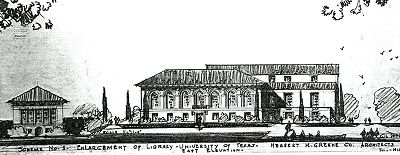

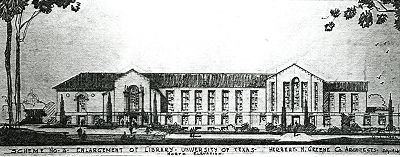

In 1926, Herbert Greene proposed an expansion of the existing library. Several schemes were presented to the Board of Regents. The Regents decided to pursue a substantial addition to the west of the building.

Additional book stacks, with the option to add a 16-story “tower,” were approved. The project, initially estimated at $200,000, grew to almost three times that amount, which at the time was beyond the University's means. The project was abandoned, though the issue remained, and the Board of Regents and Faculty Building Committee sought a new consulting architect to replace James White. Paul Cret was hired in 1930, and ultimately won approval to construct the Main Building and Tower to solve the library problem.