Subsistence and Harvest

In Mesoamerica, conversations around subsistence and harvest start with the three sisters: corn, beans, and squash. Yet every region had its own local food that influenced the livelihood of its inhabitants, whether the potato in the Andean region, cassava in the Caribbean, or salmon in the Pacific Northwest. In this section we pay homage to local cuisine and its fight for survival against colonial and imperial designs, recognizing its intimate, reciprocal relationship with humanity. As Robin Kimmerer so eloquently writes, “For what is corn, after all, but light transformed by relationship? Corn owes its existence to all four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. . . . Corn cannot exist without us to sow it and tend its growth; our beings are joined in an obligate symbiosis. From these reciprocal acts of creation arise the elements that were missing from the other attempts to create sustainable humanity: gratitude, and a capacity for reciprocity” (2013: 343). In “Cómo se siembra el maíz,” Antonio García Cruz provides instructions in Spanish and Zapotec for the traditional way to plant corn.

Unfortunately, from the Spanish ban on amaranth during the colonial period to the recent exorbitant demand for quinoa in the Global North, prompting price spikes, food and crops are as politicized as ever, thereby changing our relationship to them. This plays out in the tale of two leaves used by Indigenous groups to stave off hunger and lethargy: yerba mate and coca. Shown here as an illustration in an edition of the Argentine national epic poem, Martín Fierro (1872, yerba mate), and discussed in Historia general de las conquistas del Nuevo Reino de Granada (1688, coca), the former has become a symbol of communal bonding through a shared bombilla and the latter is best known as the main ingredient in cocaine.

As with quinoa and coca, foreign markets, often Western, have impacted subsistence and harvest in interesting ways. Catalina Delgado-Trunk’s Corazón del cacao (undated) visualizes the importance of chocolate in Mesoamerican culture, where it was used ceremonially and medicinally among different groups. Often served as a drink, Mesoamerican chocolate had bitter notes of chile or peanut. Since this did not appeal to the European palate, it also reminds the viewer how the bitter taste has been sweetened with sugar to make the product more accessible in certain markets.

Sugar, key to the popularization of global crops including cacao, tea, and coffee, once dominated Caribbean society. It was none other than Christopher Columbus who brought the first sugar cane seed to the Americas, setting the world on a trajectory that included the mass enslavement of Indigenous and African peoples and the eventual indentured servitude of Asian peoples. Here we see the relationship between humanity and a crop change from intimate and honored to one of exploitation.

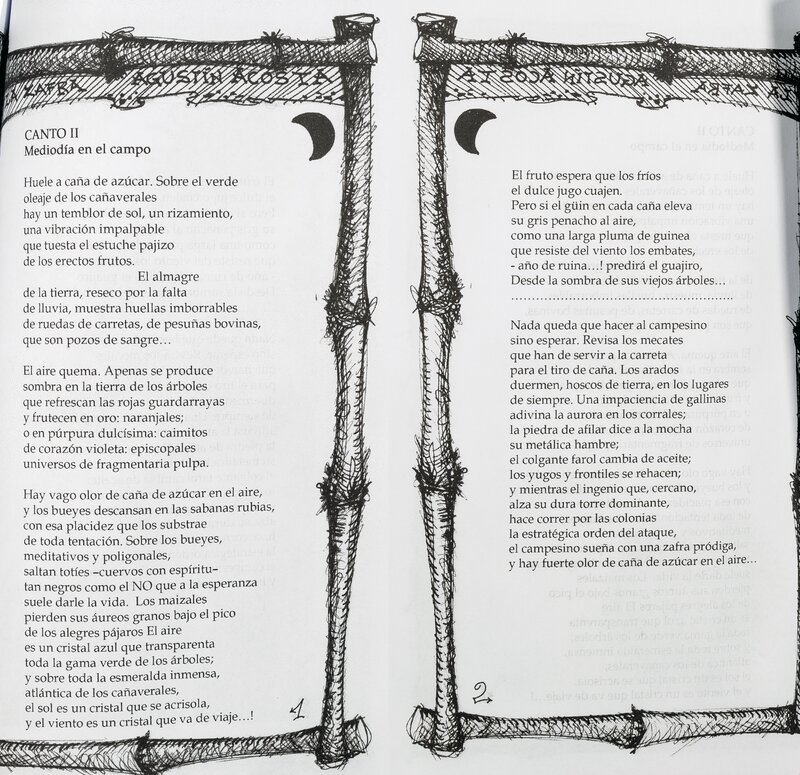

Sugar became such a monocrop that when its price declined dramatically in the early twentieth century, sugar-producing islands had little to fall back on for economic drivers. The English cartographer Thomas Jefferys touches on the potential of sugar in Compendious description of the West-Indies and General description of the West Indies (1775), while Cuban Agustin Acosta’s “Mediodía al campo” (1926), here published as a 2016 cartonera, discusses the intense labor of harvesting sugar as the world heads toward the Great Depression.

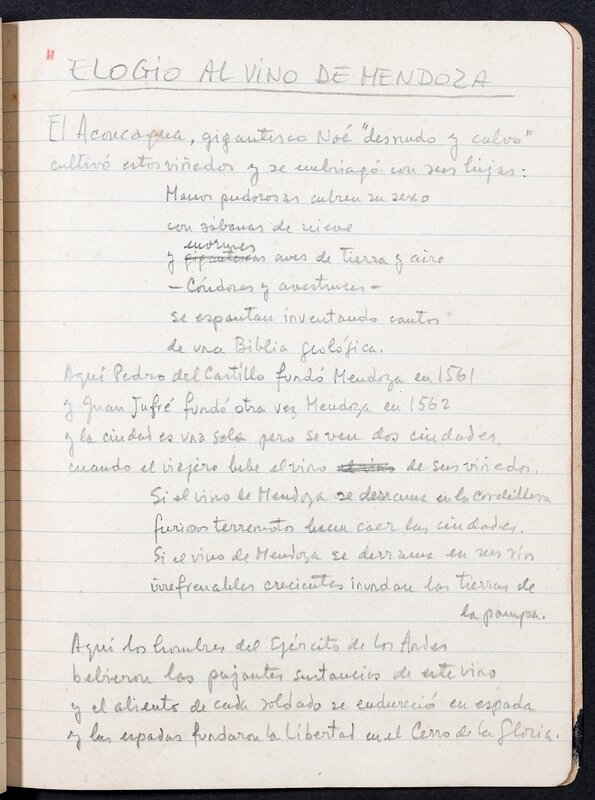

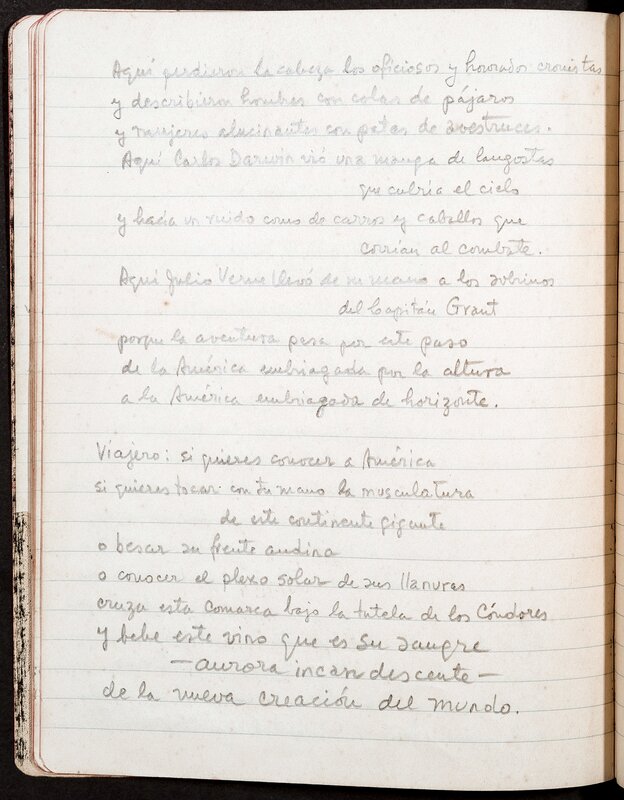

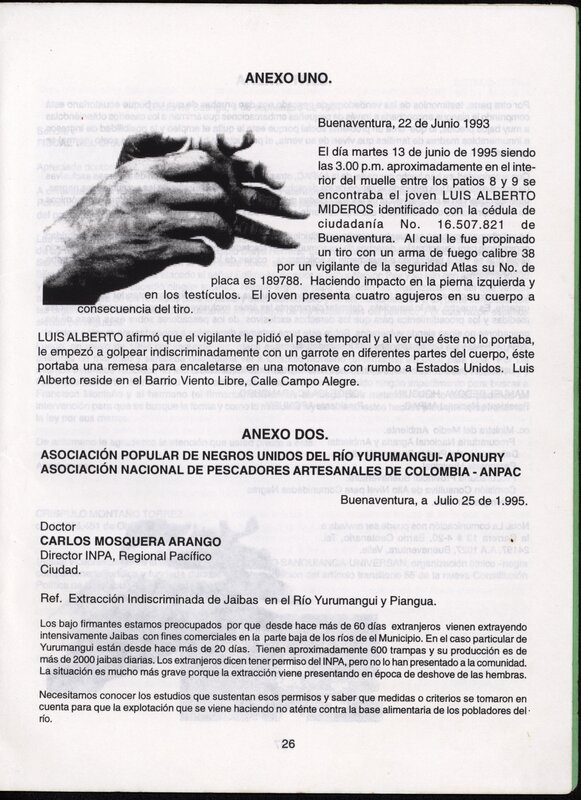

Sugar is discussed here knowing that it is not autochthonous to the Americas, and to demonstrate the role that subsistence and harvest has played as a marker of both possession and dispossession. For instance, Cuadra’s “Elogio al vino de Mendoza” (undated), must be read with the understanding that the majority of the vineyards in Mendoza, Argentina are now foreign-owned. This notion comes up yet again in Carlos Mosquera Arango’s “Anexo dos,” a fragment of Proceso de Comunidades Negras’ newsletter Comunidades negras y derechos humanos en Colombia (1992) in which foreign companies are decried for overfishing the region’s crabs.

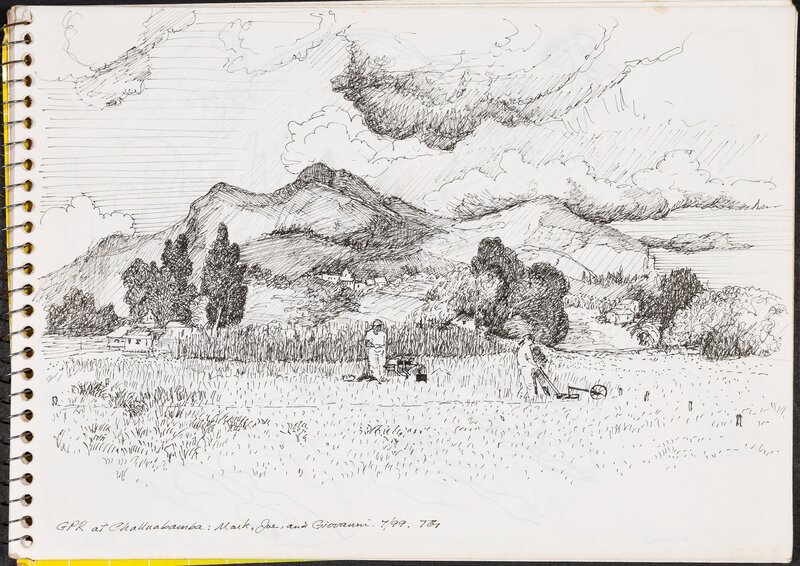

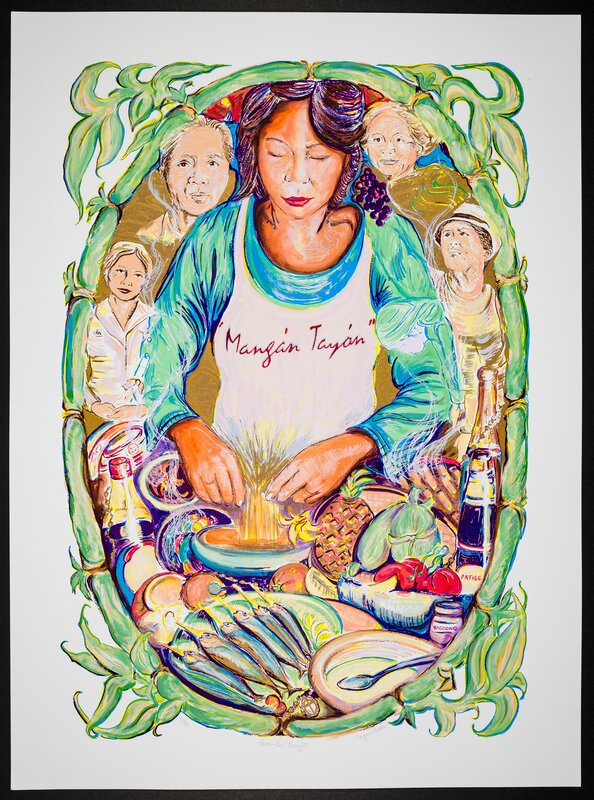

Finally, Terence Grieder’s drawing of GPR at Challuabamba (Ecuador, 1999) portrays harvesting from a visual perspective. Cristina Miguel Mullen’s Mangán Tayón – Food for Thought (2001) celebrates subsistence and harvest in the kitchen, where traditional cuisine can instill notions of identity, comfort, and culture. Such is the case in Miguel Mullen’s work, as images of family surround a woman as she prepares a meal replete with ingredients that represent her Filipino heritage.