Medicine

Before medicine was big business, nature was the first doctor. To some extent it still is, given that 25 percent of all drugs used in 2021 are derived from plants found in the Amazon. While Western medicine has many benefits, it is not without its issues, such as adverse side effects, cost, and accessibility. This is leading people to reassess the value of traditional and local knowledge. This section features traditional knowledge. Whether influenced by Indigenous, Latinx, or African expertise, traditional healing influenced by shamanism or curanderismo continues to be a primary option for care in some communities because even though it is often stigmatized in the medical field, “the practice allows families to maintain elements of their culture, and their beliefs and identities, as traditional healing practices are passed on generationally” (Sanchez, 2018: 149). The following items provide insight into natural options.

Agustín Farfán’s El tratado breve de la medicina y de todas las enfermedades (1592) considers possible local remedies for those communities out in the provinces that do not have easy access to a local doctor. Farfán, who had already published a book on surgery, was considered an expert for his era, and remedies include the curative properties of roots, plants, and animals. Although Farfán’s book is an early alternative born out of a lack of access, access remains an issue in the twenty-first century, and thus, alternative treatment options continue to pervade the conversation.

José Costa Leite’s O Matuto e o Cigano ou as Plantas Medicinais (1983) and Victoria DeLeón’s zine Grow Some Shit (undated) offer new, modern inflections on traditional knowledge. In O Matuto, a farmer rebukes a palm-reader’s offer of a reading, saying he only needs God and certain plants to sustain good health.

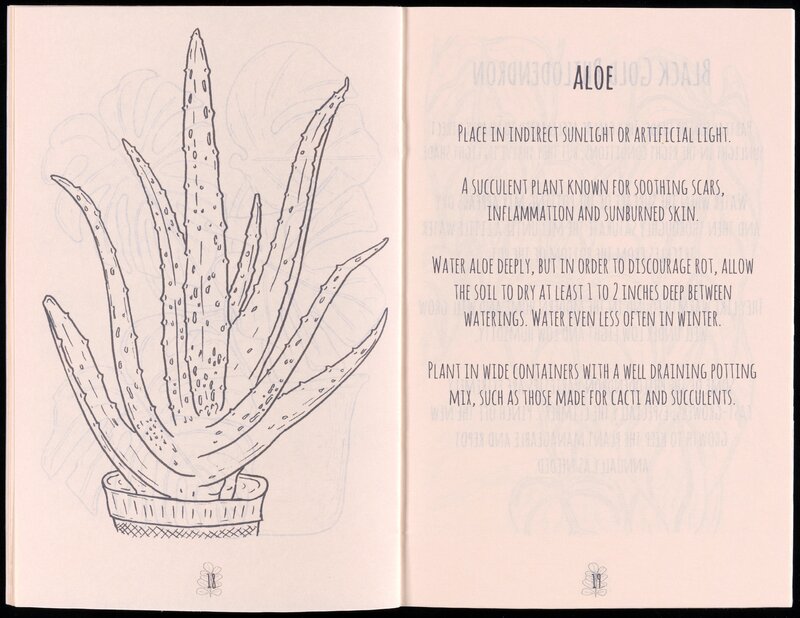

DeLeón’s didactic zine shows readers how to care for a plant (aloe vera) that will reciprocate care. Her work is one of many that carves out women’s space and participation in medicine, particularly through traditional healing. Carmen Lomas Garza’s Earache Treatment/Ventosa (2007) recalls a secondary use of newspapers to create a funnel that sucks out the moisture of an aching ear. These works posit the notion of not only traditional knowledge, but multigenerational knowledge that is shared among family and community members as such healers, midwives, and curanderas. In “Partera” (1993), here presented in Spanish and Zoque/Soteapan, the speaker tells the story of her grandmother’s role as a midwife.

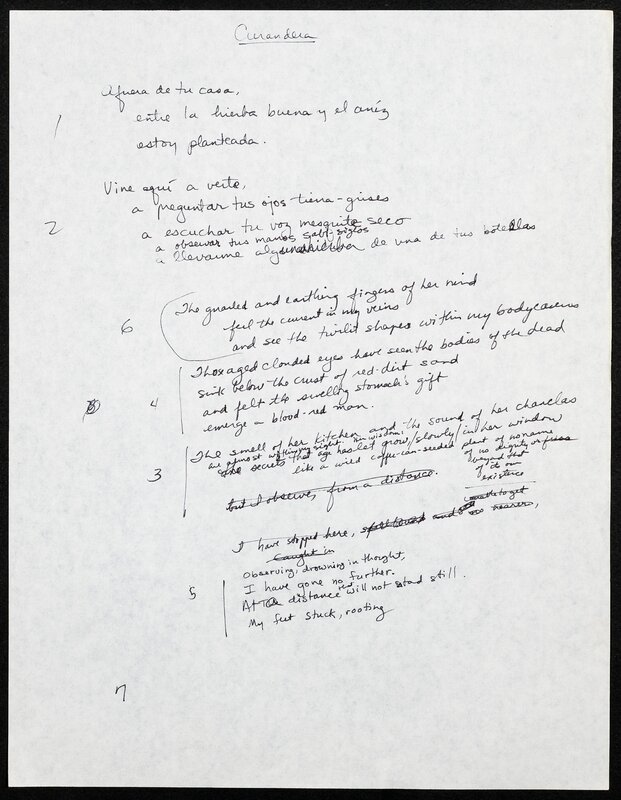

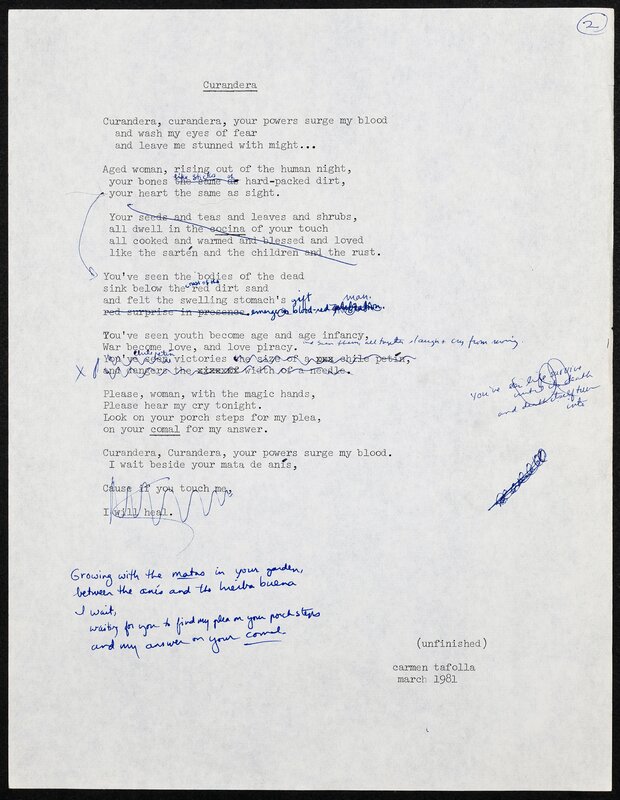

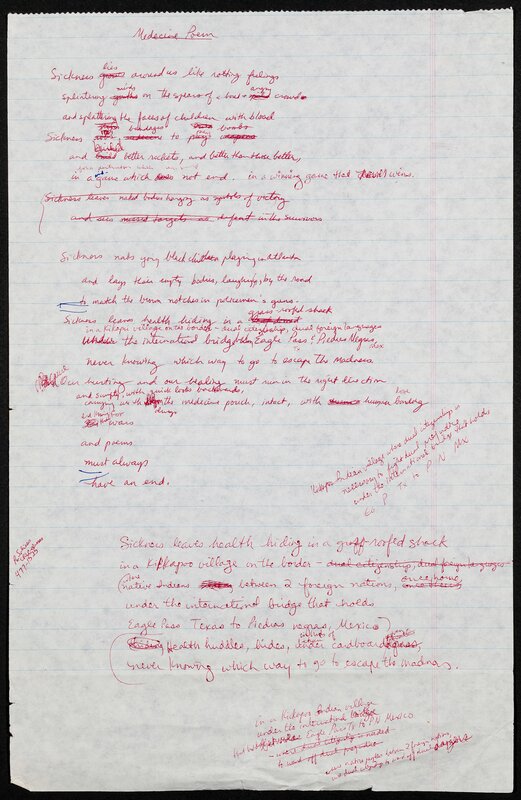

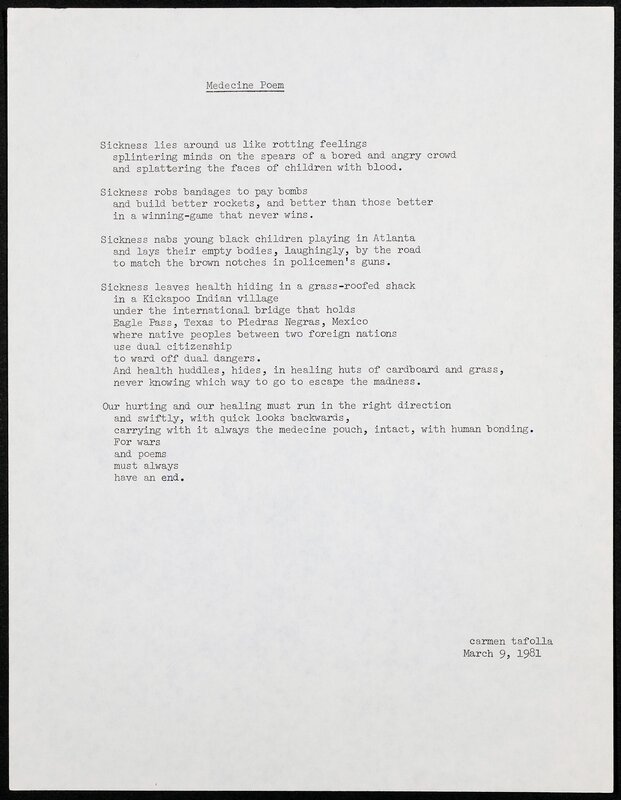

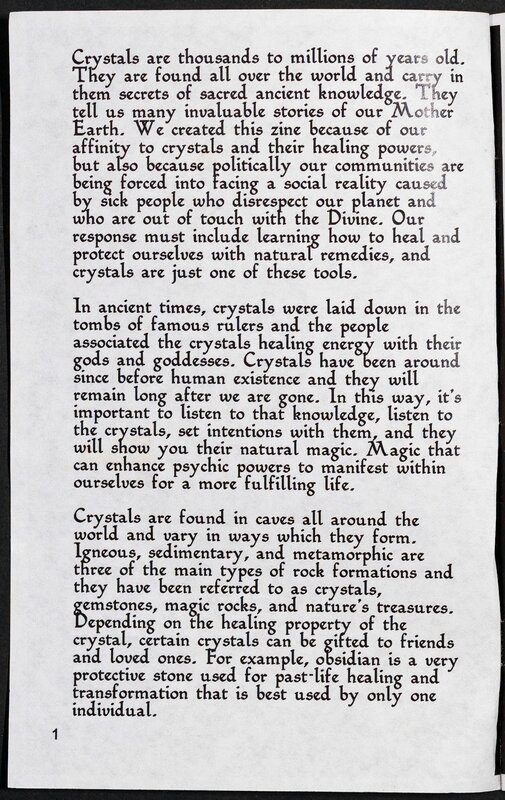

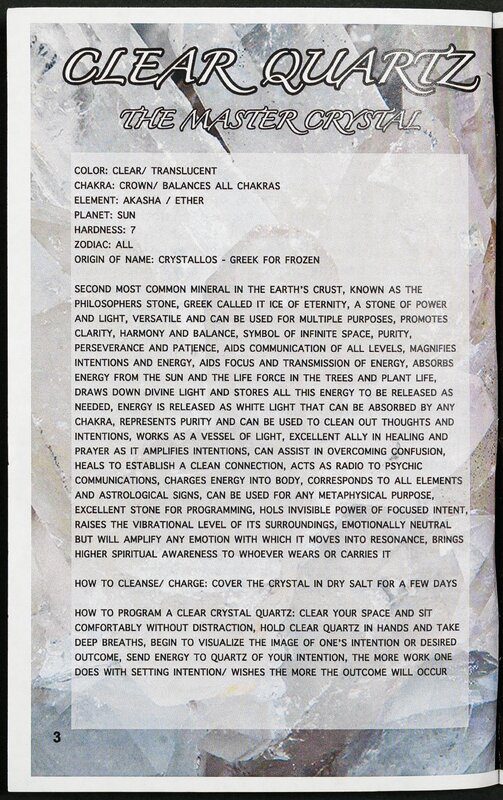

Carmen Tafolla’s various drafts of “Curandera” (1981) speak to this feminist space as Tafolla seamlessly switches between English and Spanish to describe the subject’s powers. In “Medicine Poem” (1981), Tafolla returns to the theme of sickness, this time emanating from widespread injustice and oppression. We finish this section with Colectiva Cósmica’s Crystal Zine (undated), which considers the healing powers of crystals as a popular alternative to medicine for their energizing and healing properties and their possibility to foster balance and harmony.

We finish this section with Colectiva Cósmica’s Crystal Zine (undated), which considers the healing powers of crystals as a popular alternative to medicine for their energizing and healing properties and their possibility to foster balance and harmony.