Confronting the Instability of Early Republican State Formation

A law, a decree, and a manifesto -- two from Colombia and one from Mexico -- all share a similar story. The highest rungs of republican rule that emerged from Spanish American independence produced these three documents, and each seeks to assert top-down stability and control in their respective countries. While the Colombian law from 1826 suggests how the state intended to relate to independent indigenous nations occupying territories the Colombian regime claimed in the name of the nation, the 1828 decree by Simon Bolivar suspends Colombian constitutional rule altogether. Despite laws, territorial claims, and constitutions, the Gran Colombian government was on the verge of falling apart. The manifesto issued by the self-proclaimed governing body that had toppled Emperor Iturbide in Mexico also tries to convey legal authority, stability, and the right to rule, despite clear challenges to its legitimacy. All three documents illustrate how early republican leaders faced political uncertainty by issuing laws, decrees, and official statements intended to produce stability.

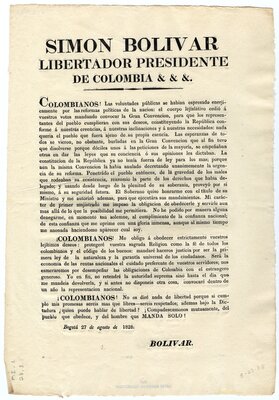

This document, disseminated in 1828, amplified Simón Bolívar's efforts to justify his newly claimed dictatorial powers through an appeal to legitimacy and nationalism: "Colombianos! I force myself to obey your strict and legitimate desires." Bolívar was one of the most important military and political leaders of independence in Colombia and Venezuela during the early 19th century, but by 1828, Bolívar’s vision for Gran Colombia was endangered by combative political factions. In an effort to regain control, Bolívar took increasingly bold measures to ensure the future of this republic. In this document, Bolívar explains how his plans to suspend Colombia’s Constitutional Assembly and enact a dictatorship will protect the freedom and unity of all Colombians in the long run. Bolívar’s willingness to suspend democracy illustrates the political instability rife throughout Gran Colombia in the late 1820s and raises intriguing questions about the fractious history of independence and unity in Latin America.

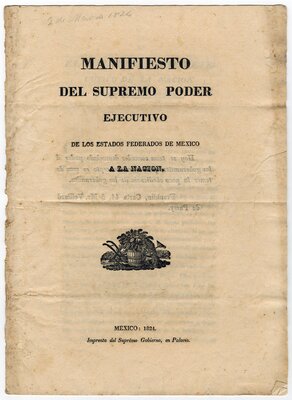

The large, bold, solid typeface announces that the Supreme Executive Power of the Federated States of Mexico issued this 9-page Manifesto in 1824, adorned by an image of agricultural equipment and abundance, rather than the bellicose Mexican eagle perched on a cactus. Through the circulation of the document, the acting head of state, Vicente Guerrero, clearly sought to assure Mexicans that stability and prosperity would come. Mexico was in a state of crisis following the collapse of the Mexican Empire under Agustín de Iturbide and a triumvirate formed, known as the Supreme Executive Power. The triumvirate was responsible for convincing states that were wavering to unify under a new Republic. The manifesto is a plea to the people of Mexico to set aside past differences and quarrels in favor of unity.

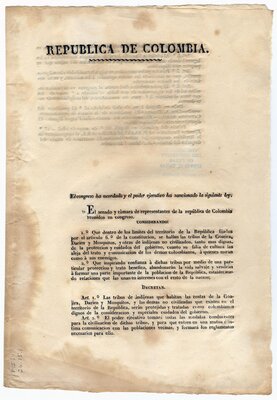

Strikingly, this law, passed by the Colombian Republic in 1826, incorporates the Independent Indian nations of the Goajira, the Darien, and the Mosquitos as subject to Colombian jurisdiction and control. These tribes populated territories up to what is now modern-day Nicaragua and Honduras. If Colombia succeeded in its attempts to claim sovereignty, then it would also have had legitimate claims on the territories occupied by these independent Indian tribes. The year Colombia issued this law, the United Provinces were still working out their newly formed territory. The claim by Colombia that it would "civilize" Independent Indians is nevertheless problematic. The Colombian Republic's decree may have declared that the government would pursue "any means necessary" to "civilize" the indigenous groups deemed a threat by local populations, but the instability of the 1820s would render such declarations moot. Even if the Colombian government did deploy troops to the region, the real threat of retaliation by these independent Indian groups discouraged such actions.