Preventing Disease in a Connected World through Public Health

The nineteenth century marked a significant time of growing global connections among humans, as evidenced by the fast-paced spread of deadly diseases and increasing international efforts to combat them. During this period, health practitioners saw the benefits of public health initiatives. Rather than healing an individual diseased body, doctors diagnosed, treated, and healed through community interventions. As the disease-causing bacteria that produced cholera made their way across the Atlantic for the first time, leading to an outbreak in Mexico in 1833, public health initiatives followed. The dissemination of guidelines to prevent cholera helped bring together opposite sides of the Atlantic into one health community. More than 80 years later, public health initiatives in Panama worked to prevent Malaria and Yellow Fever from killing the community of workers, aiding the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914. The Atlantic and Pacific oceans were connected across Central America, fostering even greater global connections.

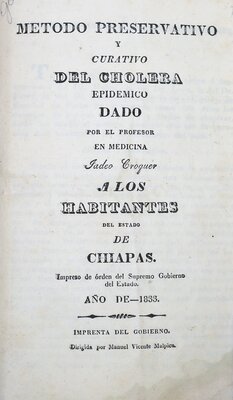

According to this pamphlet, printed in Chiapas, Mexico in 1833, to prevent cholera one must “avoid all feelings of anger, fear, sadness.” The Chiapas governor commissioned Tadeo Croquer, a professor of medicine, to produce the booklet which contains guidelines for preventing and treating cholera during the 1833 outbreak. It references instructions given by the Health Council of Paris, indicating a wide distribution of their recommendations. Included with cleanliness standards are more unusual advice like the above quote, as well as subtle criticisms of the perceived overindulgence and propensity for the poor health of the lower class. Regardless, the booklet reveals that state officials and the medical community viewed the Cholera epidemic not simply as a local or country-wide issue, but in the context of a global health crisis.

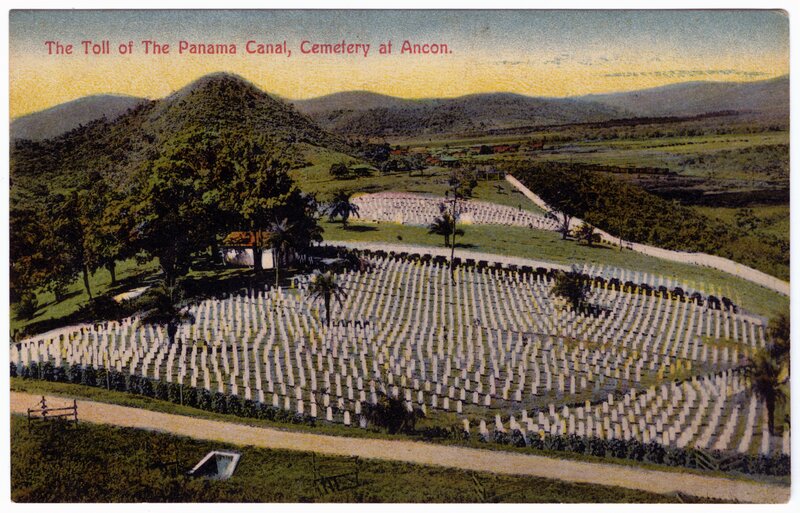

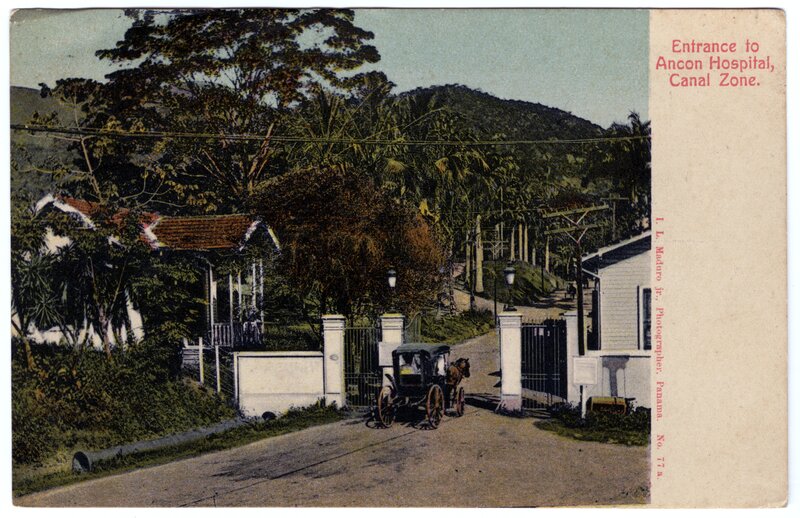

These two postcards from the J.E. Shaw collection begin to illustrate the chilling death toll that claimed the lives of approximately 25,000 people during the construction of the Panama Canal from French efforts in the late 19th century until it was completed in 1914 by the U.S. The first postcard shows the narrow path to the local hospital in the Panama Canal Zone that many canal builders, unfortunately, found themselves traveling down. The second postcard portrays the cemetery that includes hundreds of headstones marking the final resting places of the dead. The number of dead left in the wake of the building of the Panama Canal suggests the high price humans paid to achieve modernization and progress in the 19th and 20th centuries. The diseases that spread during the building of the Panama Canal also contributed to the development of public health initiatives in Latin America. Because so many people died of diseases while building this canal, significant efforts were made to prevent these diseases from spreading, which led to significant advances in public health practices overall.