From Porfiriato to Mexican Revolution

To understand the Mexican Revolution of 1910, one should examine the quality of life and changes in Mexico in the decades preceding the conflict. Porfirio Diaz’s presidency, colloquially called the Porfiriato, was a period of change and modernization across Mexico spanning 34 years. As Mexico developed its industrial and economic capacities, the day-to-day lives and opinions of ordinary Mexicans began to change. The focus was beyond political change: there was a focus on the social fabric, which included an emphasis on education, technology, and gender-relations. These objects are a testament to these changes. Modern trends are evident in these photographs and objects, which display how Mexico's native populations were at the center of these transformations.

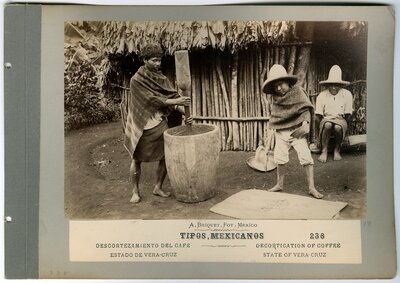

While the bare feet and simple garb of these workers may suggest primitive conditions, the labor they performed contributed quite a lot to Mexican economic productivity. The Mexican state of Veracruz has been among the first and most prolific regions in coffee production in the country. Owing to its tropical climate and abundant fertile land, agriculture thrives in the region. The region's higher altitude permits coffee production. Modernization during the reign of cult-of-personality president Porfirio Diaz, increased coffee's marketability, especially domestically, making the labor cost to refine the raw bean more worthwhile.

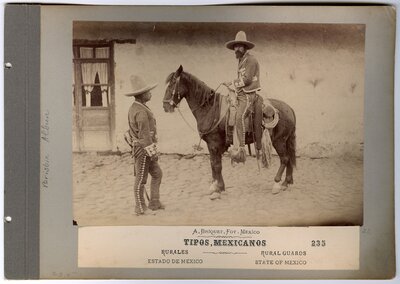

Large sombreros and extravagant clothing evoke images of charros or mariachis, but these men are rurales , the Mexican police force established by President Benito Juárez in 1861. This photo, taken in 1883, depicts two rurales during the regime of dictator Porfirio Diaz. After having been tasked with stopping banditry in the countryside during the Juárez administration, and after helping to oust the Mexican Emperor Maximillian during the French Intervention, Díaz's modernization program transformed the rurlales into a professional auxiliary military force. The rurales soon earned international fame, being likened to the Texas Rangers, for their success in imposing order over some of Mexico's most unruly localities. Defeated after having served alongside those troops loyal to Diaz during the Mexican Revolution in 1910, the rurales were officially disbanded by the revolutionaries in 1914.

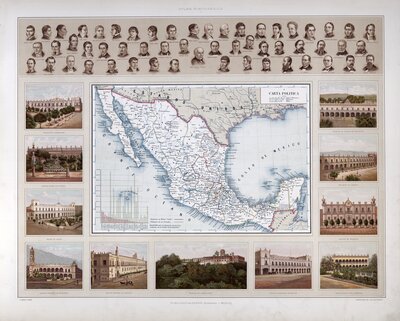

Produced in México (1885), this excerpt from Atlas Pintoresco e Histórico de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos includes a map surrounded by headshots of politicians and buildings of México, as illustrated by Antonio García Cubas. Cubas produced this work during the transition of colonial 19th century Mexico into the 20th century, led by Porfirio Diaz. This page focuses on modernity and national identity, as seen through nineteenth century Mexico's buildings and its political leaders. Other pages contrast these ideas as they contain images of indigenous populations and Mayan ruins, suggesting the diverse makeup of Mexico's population and national identity.

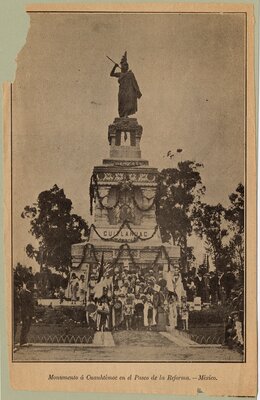

Seen as a representation of the strength and perseverance of the Mexican race, the last Aztec Emperor Cuauhtémoc was meant to be a symbol of the ‘new’ Mexico that would emerge during the Porfiriato. Pictured here towering over the Paseo de laReforma is the Monument to Cuauhtémoc. Cuauhtémoc was seen as a martyr against the Spanish Conquistadors, and similarly, he was a unifying symbol against the French occupation. Built in 1877 to the same specifications as the monuments to the figures from the Mexican War of Independence, the monument is pictured here in 1906 with some indigenous peoples honoring the glorious past of their ancestors at a time when indigenous culture was being stamped out in the name of modernity.

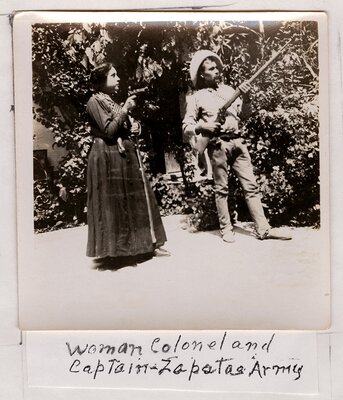

This photograph shows a Coronela, yes, a female officer, and male Capitan serving in Emiliano's Zapata army during the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Notice how the woman and man stand in equal positions, and both hold a gun. Soldaderas, also known as Adelitas, were women who played crucial roles in the Mexican Revolution. More than just care for the male soldiers by providing them with food and medicine, women also lead troops and physically took part in combat. As shown above, some revolutionary women achieved officer status. At first, they resorted to impersonating men and sneaking into the armies. Through their courage, skills, and intelligence in battle, they gained respect and enough support to reveal their real identities. Many also refused to be romantically involved with male soldiers. A famous revolutionary leader, Angela Jimenez, even pledged to her comrades that if anyone tried to allure her, she'd shoot them. Who said women couldn't do what men could?

The sanitary crew depicted in this picture, taken by Mark F. Upson in Cuernavaca, Mexico, was used by the military in the Mexican Revolution as a health measure during an influenza epidemic. Advancements such as medical and public health services during this period have often been overlooked due to the focus on the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution. However, it was during the Mexican Revolution that the health culture of Mexico drastically changed.

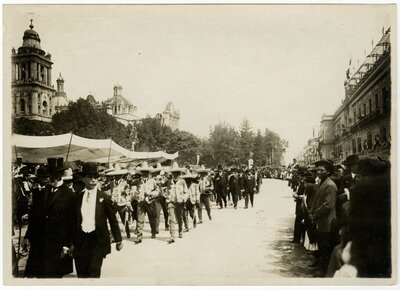

Distinguished by their extravagant uniforms and synchronized, disciplined march, the rurales, in this photograph, put their infamous, elitist image on full display. The rurales are shown taking part in a procession celebrating 100 years of Mexican independence from Spain. The rurales underwent major transformations during the nineteenth century period that closely shadow the developments of Mexico. This photograph, taken in 1910, depicts the rurales as they functioned under the late stages of the regime of Porfirio Díaz. As instruments of the Porfirian regime, the rurales were utilized as a force of repression against the discontented campesinos. Shortly after this picture was taken, the Mexican Revolution would begin and the rurales would join forces with the federales, taking up arms against the revolutionaries.

Produced in México in 1885, this excerpt from Atlas Pintoresco e Histórico de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos includes a topographical map of Mexico surrounded by images of landscapes and artifacts of pre-European Mexico. These images contrast the modernity of colonial Mexico seen throughout the Atlas (specifically in the Carta Politica) and suggest a variable national identity. Also featured is an inset map of the Valley of Mexico as a homage to the indigenous heartland and capital of Mexico.

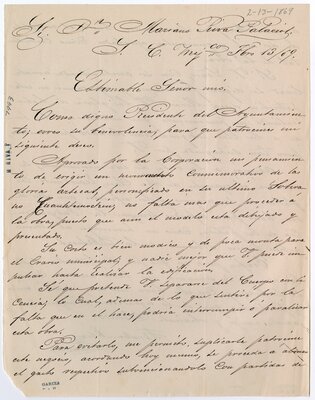

This letter from Abraham Rivera to Mariano Riva Palacio, written on February 13,1869, concerns the construction of the Monument to Cuauhtémoc on the Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City. Rivera wished to complete the statue before Palacio stepped down from his leadership position in the Adjuntamiento, and to celebrate the history of the Aztecs in the hopes that it would ‘revive the spirits of the indigenous peoples.’ Written during the Porfiriato, an era in Mexico where indigenous interests often came at odds to the States’ goal of modernization, this letter paints an importance on Aztec heritage to the new Mexican identity.

This image shows a celebration parade in Cuernavaca, Mexico, in honor of Francisco Madero’s election to presidency on November 6, 1911. The Mexican Revolution of 1910 resulted from the tyranny of President Porfirio Diaz. It was during his reelection that Francisco Madero opposed him. Diaz ruled for 30 years as dictator of Mexico. During his reign the rich prospered while the poor toiled for very low wages and some almost experienced slave-like treatment just to survive. Diaz would be reelected through bribes and by favors of the elites. He controlled the army and the press. When Madero rose up as a candidate for presidency, Diaz arrested him. Madero sparked off a revolution and urban peasants in Mexico rose up and fought for a better life. After countless battles, Diaz was finally made to resign his position of president. Zapata lead the parade in Cuernavaca, Mexico. Viva Mexico! Viva la Revolucion! “The people united, will never be divided.”

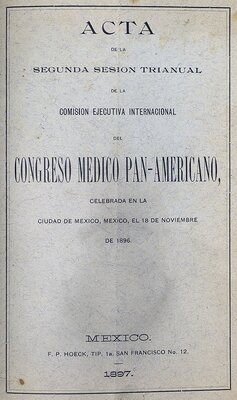

The text shown in this image is the meeting notes of the Pan-American Congress of Doctors in 1896.They assembled in Mexico City, Mexico, to constitute the organization’s role in the Western Hemisphere. This period is marked as the road to the Mexican Revolution, in part because foreign investments and relations flourished. What has been studied, however, is how the growing global relations due to Latin America’s modernity in the nineteenth century played a major role in establishing public health and medical services in the Western Hemisphere.