U.S.-Mexican War and Remembering the Forgotten Actors

During the two decades preceding the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), Indian raids decimated northern Mexican territories, making them easily susceptible to conquest by the U.S. Army. At the same time, European powers tried to reassert their control over the region, and, on the eve of the war, attempted to prevent the conflict from happening to avoid a major shift in the balance of power in the Western Hemisphere. Even though Indian raids and foreign powers influenced the outcome of the Mexican American War, they are often forgotten. Instead, textbooks emphasize that the war was a regional conflict between two neighbors rather than an international conflict with global repercussions. To fully understand the consequences of the war, we must remember forgotten players.

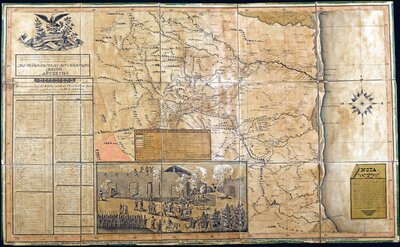

All my life I've lived in the Northeastern Mexican city of Camargo near the Rio Grande River, but strangely enough I've never known about the Indian raids that devastated Northern Mexico in the 19th century. This map displays with unparalleled accuracy the sites of conflict between the Comanche and the Tamaulipas federalist rebels during these raids. It upholds Mexico's claim to its northeastern border being the Nueces River against the claims made by independent Texas settlers who sought an international border at the Rio Grande. Indian raids devastated Northern Mexico, forcing Mexico to negotiate with the United States, believing they could call off the raids. Mexico gave up the Nueces border. Despite the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the United States could do nothing to stop Indian raids that devastated Northern Mexico for decades to come.

Textbooks and general histories often overlook the significance of the Mexican-American War to actors outside the region – in this case, Britain and France. Written in February 1845, this letter (see Figure 2) is a translation of a French newspaper article that explicitly critiques the United States for attempting to annex Texas. Translated by the British Ambassador, it reveals how both France and Great Britain shared the belief that U.S. expansion into Mexican territory posed a dangerous threat to European interests not just in Latin America, but also around the globe. Because they feared unchecked U.S. expansion, Britain and France had a significant stake in the outcome of the Mexican-American War.

The map shows the geographic landscape and movement of American and Mexican troops during the Battle for the Sacramento River, which took place on February 28th, 1847 during the Mexican-American War. Colonel Alexander Doniphan (American) commanded 1200 soldiers against Governor Trias's (Mexican) command over 3700 soldiers. The map isn't able to tell the full story of the battle. Comancheria Indian raids from 1833-1846 weakened Northern Mexico. In their wake, the American army easily defeated Mexican military forces with few losses. The battle had implications that spread further than the US and Mexico; English and French newspapers announced American victories across the Atlantic. The map is a part of the Rare Map Collection at the Benson Library.

Northern Mexico in 1853 was suffering Indian Comanche raids, despite promises by the United States to stop to them after the Mexican-American War ended. In a ploy to win support from Northern Mexico, President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna allowed local populations to keep unlicensed guns to fight off Indian raids. Santa Anna had reason to fear that armed revolution would unseat him from power, and so did not allow northern Mexicans to take unlicensed arms outside of their regions.

The copy of the letter shown here belonged to the Justice of the Peace from Hualahuises. The letter demonstrates a chain of communication that went from Santa Anna to José María Tornel, the Minister of War and Marines, to Pedro de Ampudia, the Governor of Nuevo Leon, and from Ampudia to Northern Mexico’s authorities, including this nameless justice.