Cultural Identity and Resistance

Set against the example above is the poem “Self (Reconstructed)” by Ofelia Faz-Garza. Here the access to traditional Mexican cuisine shapes her identity: mole, beans, fideo, and taquitos. Whereas Llosa Vite expresses her disconnect from her culture in “Querida Mamita,” Faz-Garza articulates her identity through food. Moreover, while food helps her to construct who she is, it also differentiates her from who she is not: “2.0 colonizers” who appropriate Mexican (American) culture and exotify People of Color. Food becomes an outlet of resistance that “Querida Mamita” cannot replicate.

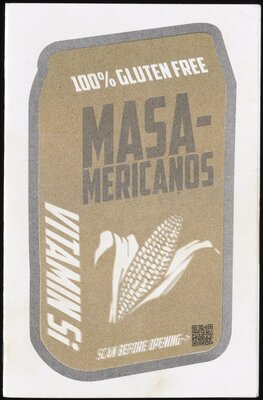

One way to “free" oneself from this struggle is to reclaim Native foods while avoiding processed foods with high amounts of sugar. The mention of maize is intentional. Corn is native to the Americas and frequently referred to as one of the three sisters of Indigenous sustenance (along with beans and squash). Unlike other crops, corn is not found naturally. In other words, it relies on human cultivation. The history of many of the Original Peoples of the Americas is therefore inextricably linked to maize; as Jeffrey Pilcher points out, corn “gradually diffused through much of North America in the first millennium of the Common Era” and with it, the tortilla (2011, p. 4). Subsequently, corn marks Latino and Latin American cuisine today, such as arepas, gorditas, tamales, atole, pupusas, and posole. Mary Agnes Rodriguez’s artwork on corn in Yes Ma’am’s Vegan Issue and Mercado Merch’s cover Masa-mericanos highlights this history. These foods are able to stay relevant in the United States because of renewed immigration and large enclaves across the country (Anderson, p. 203). Rodriguez’s piece privileges the relationship between the crop and the cultivator by placing the hand and corn stalk together. This connection to the land permits people to stay rooted in a sense of place and identity. Valuing that local production, particularly with a vegetable that is a staple of Latino gastronomy, is a way to resist the globalized market.

Masa-mericanos offers a more humorous tone. The drawing of the corn appears as the art on a packaged good that one would find in a grocery. “100% gluten free” alludes to the recent trend of gluten-free diets in the United States. At the same time, it recognizes corn’s healthy attributes: the fact that it is gluten free suggests that anyone can enjoy it. “Masa-mericanos” plays with the words “masa” (dough that can be used to make a tortilla) and “americanos” (Americans). “Americanos” can refer to people living in the Americas broadly, or those specific to the United States. In the former, the title creates a larger, hemispheric sense of solidarity while also warning of the growing Americanization of supermarkets. In the latter, it emphasizes the United States’ eagerness to purchase pre-packaged masa to privilege efficiency. But doing so ignores the traditional way of grinding corn with a metate, usually accompanied by communal and generational storytelling. This type of storytelling maintains cultural values and opens up the possibilities for the sharing of traditional knowledge.

![[Maize]](https://spotlight-prod.lib.utexas.edu/images/571/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)

![[Not knowing how your tia passed a huge smelly fish]](https://spotlight-prod.lib.utexas.edu/images/167/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)