The "Relaciones Geográficas"

The manuscript documents and accompanying maps known as the Relaciones Geográficas are responses to a questionnaire issued by the king of Spain in 1577 to survey the territories of the Spanish American colonies. The questionnaire, distributed to officials in the viceroyalties of New Spain (now Mexico) and Peru, requested basic information about the nature and characteristics of their lands and the lives of their peoples.

The replies were completed by local colonial officials and indigenous notaries and scribes, and they offer historical, cultural, and geographical details of communities in New Spain in the sixteenth century and before the conquest. Many of the written responses included hand-drawn and painted maps, called pinturas. These maps were the work of indigenous artists, many of whom were educated by the Spanish, but were also trained in pre-Hispanic writing and artistic practices. The artists’ use of both traditions of visual representation in the pinturas of the Relaciones Geográficas make these maps rich sources of information about the many-layered cultures of early colonial communities in New Spain.

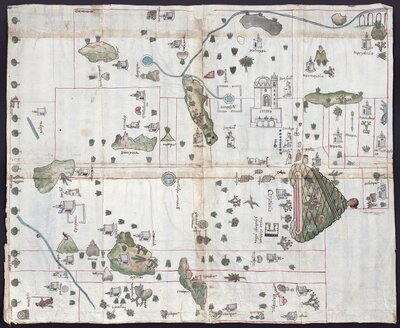

The pintura of Cempoala is particularly rich in indigenous iconography marking places, people, and topography. The large hill topped by the head of a Totonac (indigenous group native to Cempoala) is a perfect example of the hill symbol—tepetl in Nahua—that represents place. Atl, water, seen here in the waterway and aqueduct at left, is another frequent visual feature of indigenous maps, and the Nahua word altepetl, akin to city-state, comes from these two words, atl and tepetl, because a water source and a defensive hill were integral to the founding of a settlement.

Pictographs on the map also represent the complexity of Cempoala’s colonial social and political order. Local Nahua rulers in noble tilmahtli(cloaks) and headgear and Otomi natives wearing hides are easily distinguished by their dress, as is the Spanish official seated at bottom right in his colonial folding chair. The grid that underlays all of these figures suggests the division of lands that pertain to Cempoala’s altepetls and the smaller communities they each contained.

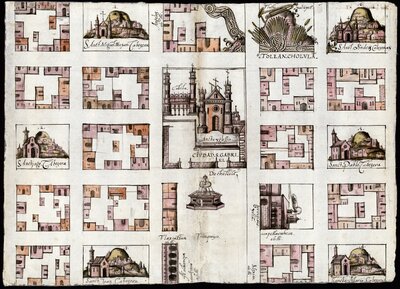

The Cholula map’s orderly grid plan and refined architectural details offer a Europeanized vision of the city influenced by Renaissance aesthetic ideals. Yet Mesoamerican elements are still very much present in this view of Cholula. Each of the six churches numbered and labeled around the perimeter of the map traces the location of a pre-Hispanic calpolli (district), and the traditional tianguis (marketplace) still takes pride of place in the plaza that fronts the cathedral. At top right, the city’s ancient pyramid, a site of violent conflict during the conquest, seems to explode from the well-ordered bounds of the map, labeling Cholula “Tollan,” a reference to a mythical pre-Hispanic civilization.

Like many of the Relaciones Geográficas maps, the Cholula map is colored with a mix of European pigments and indigenous ones such as cochineal. The paper here is European, but some of the other pinturas were done on indigenous amate paper.

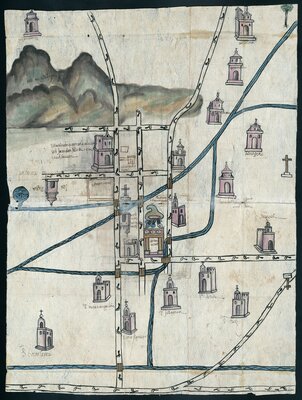

Most of the Relaciones maps give no indication of their artists’ identities. But the creator of the Culhuacán pintura, Pedro de San Agustín, is named on the back of the map. Painting was the occupation of an educated native elite, and San Agustín was part of Culhuacán’s political leadership, serving as an indigenous official of the city during the 1580s. He very likely studied at the Augustinian monastery school in Culhuacán, the large building pictured just under the hill at the map’s left. His inclusion of the town’s paper mill, adjacent to the monastery, further indicates his ties to elite forms of colonial cultural production.

Alongside the many markers of San Agustín’s Spanish training, his pintura is rich with indigenous visual elements. He features at center the distinctive place-name symbol of the city—a hill with a colli (curve) at top that refers by the word’s sound to the native Culhua people. He paints the running water of the main ojo de agua (water source) and its streams, and he marks the roads that cross Culhuacán and connect it to other communities with a footstep pattern found in centuries of native painting.