Hänsel and Gretel

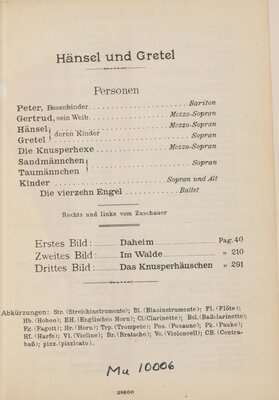

Following Wagner’s last opera, Parsifal (1883), and his death a year later, composers were unsure how to move the art forward from his epic musical dramas. Some composers, such as Engelbert Humperdinck, decided it was best to work backwards, composing rich scores, incorporating simple folk melodies for fairy-tale adaptations. Humperdinck and his sister, Adelaide Wette’s opera Hansel Unt Gretel (1893) draws inspiration from the Brothers’ Grimm Hansel and Gretel. Their three-act opera cultivated a universal music style, cementing a romantic philosophy that children are divinely scared. One of Wette’s key adaptational changes to the beloved fairy tale is the inclusion of angels. In the original story, Hansel and Gretel learn to save themselves through trickery, but in the opera, the children sing a lullaby, “Evening Prayer,” to call upon fourteen angels for protection as they sleep alone in the woods. This act of musical innocence saves the children, not themselves. Under these alterations, Wette keeps the children naive and does not allow them to mature organically, for them to transcend their own nature via maturity and self-reliance. In spite of these changes, or because of them, Hansel Unt Gretel remains a delightful opera that continues to be performed for children.

For an in-depth examination of the score and critical reception, I recommend reading T.F. Coombes, “(Trans)National Fairy Tale and Romantic Childhood: Humperdinck’s Hänsel Und Gretel through Its Parisian Reception,” Cambridge Opera Journal 33 (2021): 50-70.