Mexican National Identity

Together these three documents reveal how the Mexican struggle to secure independence from monarchies – from 1810-1824 against Spain, and from 1862-1867 against the French-imposed emperor Maximilian - produced a distinctly Mexican identity linked to upholding democracy. This nascent national identity was utilized both as a source of political authority and as a foundation for a Mexican nationalism rooted in pride for democratic values. Jose Maria Heredia’s commemoration of Mexican Independence in an 1836 speech blends historical accounts of independence against the Spanish Monarchy with poetic license and language to define a distinctly Mexican history. Historical heroes like Padre Hidalgo stood for values of democracy and liberty that became a source of Mexican national pride. By 1910, Hidalgo was used in an effort to legitimize Porfirio Diaz’s floundering claim to the Mexican presidency after over three decades of rule. Díaz’s supporters also drew on a more recent struggle for independence to support Porfirio’s election. Diaz’s nephew, Felix Diaz, appealed to national pride in values of voting and celebration of the national holiday of Cinco de Mayo - a victory over French forces in Puebla, Mexico which brought Porfirio, merely a young army officer at the time, to national fame. Felix’s status as a general reflected Porfirio’s military history in Mexico and garnered a sense of unity that came from fending off invasions.

"Speech given at the civic festival of Toluca," title page

This circular of a speech delivered by Jose Maria Heredia during an 1836 Independence Day celebration in Toluca, Mexico was bound by a collector between religious pamphlets and political proclamations. Heredia’s speech reveals how notions of national identity and history were established in Latin American through commemoration. Public festivals for religious and governmental events were an important part of life in colonial Latin America. After independence, festivals became a way for political and intellectual elites to promote public introspection through commemorative speeches. Heredia, a Cuban-born poet who settled in Mexico in the 1820’s, was one such intellectual. In his speech, Heredia mythologizes key figures of Mexican independence like Padre Hidalgo and Agustín de Iturbide into national martyrs for Mexico. Heredia accomplishes this through poetic language – likening the cry (grito) for independence to “...the cry that shook Anáhuac (Azetc Mexico) from a three-hundred-year slumber”. By repeating these narratives at regular celebrations, speakers like Heredia promoted a collective national memory for what Mexican history needed to mean.

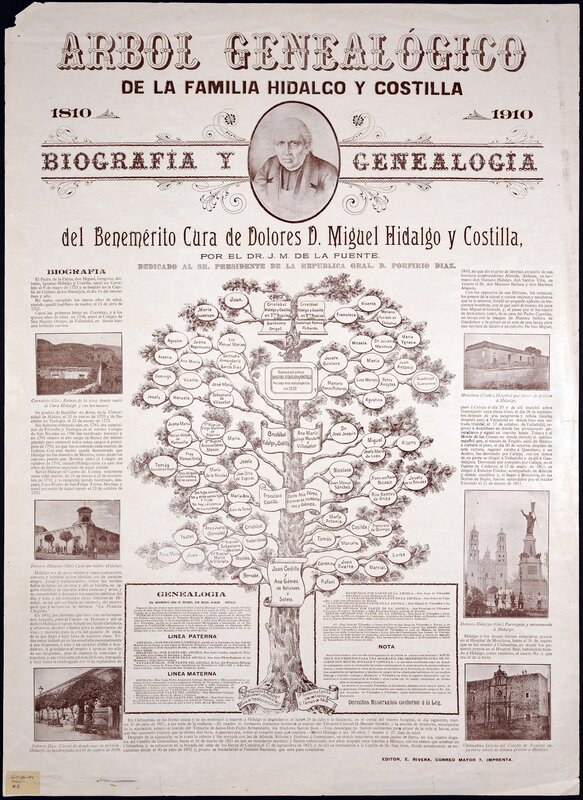

"Genealogical Tree of the Hidalgo y Costilla Family, 1810-1910"

Centered are the parallel names of Miguel Hidalgo and President Porfirio Diaz standing side by side in direct comparison surrounded by descendants of the founding missionary-turned-freedom fighter of Mexico, Miguel Hidalgo. In 1910 on the eve of the centennial of Mexico’s independence from Spain and with a surging no-reelection campaign, long time incumbent Diaz inaugurated celebrations while drawing comparisons with the mythologized hero of Mexico. Hidalgo holds a special place in the hearts of Mexicans as the formerly peaceful missionary underwent a politicization and militarization to pursue a dream of a Mexico free from imperial Spain. Diaz hoped to benefit from this fond remembrance and use it for political power. Sources from this period gave a glimpse into how national celebrations are used to create a sense of nationalism, legitimate a fragile grip on power, and exploit memory for political gain.

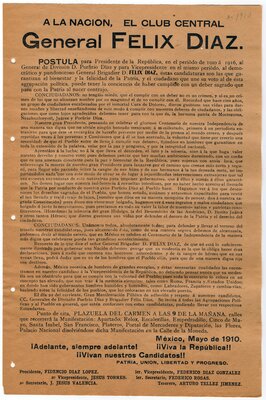

"To the Nation, the Central Club, General Felix Diaz"

A unique, modern font proclaiming the name “General Felix Diaz” -- the nephew of Porfirio Diaz, Mexico’s president for over thirty years– drew the eyes of passing citizens to this broadside. Not immediately visible then but made clear through a deeper understanding of Mexican politics is why Porfirio used the military in his advertisement. By reminding citizens not only of military officials sharing his name, but also of Cinco de Mayo, Diaz invoked a sense of national identity and unity. Although not a victory that prevented the French conquering Mexico, Cinco de Mayo stood to remind the citizens of the greatness that came from working together for a common goal. Another such victory to be shared by Mexican citizens? Democracy. What better way to celebrate than voting? Specifically, voting for Porfirio Diaz, who embodied these values. This broadside made one message clear: Mexican citizens who fought for independence and democracy vote for Diaz.