Education in Revolutionary Latin America

Education became a critical avenue through which Latin American governments experimented with creating democratic polities that fostered inclusion and equality after gaining independence from Spanish monarchical rule. This collection of documents from mid to late 19th century México and Bolivia contains a speech transcription, a letter, a report, and a circular. Collectively, these documents detail the ways in which revolutionary governments utilized education to propagate ideas that characterized the progressive regimes such as nationalist ideologies, moral Catholicism, and nominal gender equality. In doing so, these sources also reveal the selectivity with which such ideas were applied. For example, these documents outline the progress made in expanding educational access to women, even though universal suffrage would not be realized until the 20th century. Analysis of these documents underscores that governments expanded rights when convenient, while actively withholding rights when necessary.

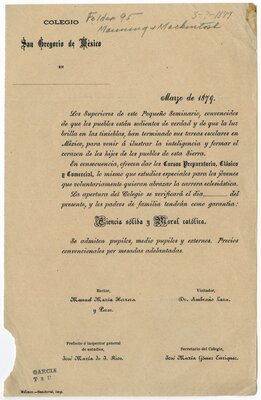

Circular from the College of San Gregorio of Mexico advertising its course enrollment period

In bold cursive letters of the circular sent out by Colegio San Gregorio de Mexico in 1879 are the words “Ciencia sólida y Moral Católica” which puts emphasis students will receive solid scientific studies as well as a moral Catholic Education. This object was produced at the intersection of church and state under the Porfiriato and clears up misconceptions that the church and Mexican government have always been united. Porfirio Diaz’s predecessor, Benito Juarez was committed to removal of the clergy from predominance in education. In contrast, looking at the Porfiriato, the state becomes more interconnected with the Catholic church, and Diaz promotes a catholic education combined with a commercial and scientific education.

"Exhibition presented by the Ministry of State in the Departments of Worship and Public Instruction to the Legislative Chambers of the Bolivian Republic," title page

This original, elaborately printed government report—complete with a seal—describes the state of religious and secular education in Bolivia in 1850. Education systems were critical for nation- building post-independence in Latin America. This report, written by minister José Agustín de la Tapia, engages with the Bolivian history curriculum and recommends emphasizing the “grand history” of Bolivia with its “democratic renovation” to spread the ideology of Latin America’s political modernity. At this time, Latin American nations like Bolivia asserted the political modernity of their progressive democracies—in contrast to European monarchies. Close reading of this report together with other documents in this exhibit illustrates how deeply woven into 19th Century Latin American history was this ideal of political modernity.

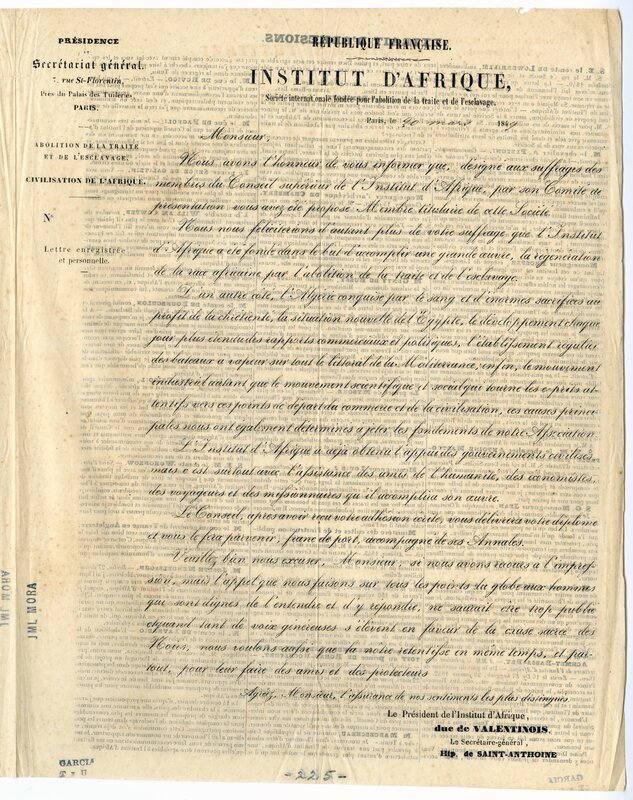

Letter from the African Institute to its readership regarding state of affairs in worldwide manumission efforts

José María Luis Mora’s letter from the Insitut D’Afrique, as part of his Correspondence, demonstrates the remarkable lengths he went through to remodel the education system in Mexico. The letter comes from Secretary General Jarisarlloire, the head of the institute, and was sent in 1849. The Insitut D’Afrique is a French cultural and scientific institute stationed in Africa. After taking notice of Mora’s efforts to crack down on segregation in schools, they request to become one of his members. They believed that joining with Mora would work towards abolishing the slave trade. The letter can tie into other works about either education, racism, or reshaping general society in Mexico. It shows the significance of Mora’s reformation efforts to change the educational system and inspire better experiences for students, as seen in works like Harold Benjamin’s Revolutionary Education in Mexico.