A New Mexico

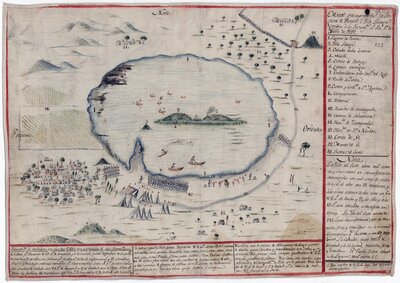

Map of the Yuriria Lagoon and Liceaga Island during the war for Mexican Independence by an unidentified artist, 1812. Royalist troops surrounded the lagoon and overtook the insurgents that occupied the island.

In 1808, the army of French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte occupied the Spanish kingdoms of Navarre and Catalonia. The invasion was precisely what Spaniards feared when Charles IV, the King of Spain, let French troops cross Spain to attack Portugal in the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1807). By this point, the Spanish nobility—particularly Prince Ferdinand—had come to resent Charles IV’s ineptitude and the authority of prime minister Manuel Godoy, who had ascended to power from humble origins.

Exacerbated by the ongoing economic trade crisis that resulted from the loss of the Spanish navy in the Battle of Trafalgar (1804), the town of Aranjuez rose up against the king and Godoy March 17-19. Siding with the rebels, the Spanish Royal Council forced Charles IV to abdicate and made his son Ferdinand VII king. Each seeking acknowledgement as the legitimate ruler of Spain, the father and son soon turned to Napoleon, who in turn dethroned them both on May 5.

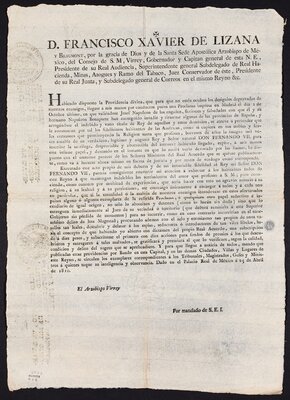

The following month, Bonaparte installed his brother Joseph as king, bringing Spain into the French fold. Attempting to address the resulting power vacuum and counter the French invasion, former and new regional governing councils emerged throughout Spain, eventually coalescing under the authority of the Supreme Council at Aranjuez in September 25. In New Spain, Archbishop-Viceroy Lizana y Beaumont and other officials made public proclamations like the ones shown here against the French usurpation.

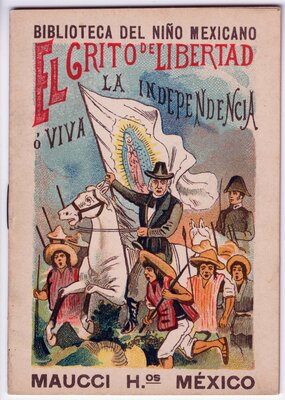

Drought, economic inflation, and the devastating effect on the laboring Indigenous class led to Father Miguel Hidalgo’s Grito, or the yell for independence. While Hidalgo, Doña Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez, and other members of a local literary club in the town of Dolores (in present-day Hidalgo, Guanajuato) advocated loyalty for Ferdinand VII, they argued that many gachupines, or peninsulares, served Napoleon; thus, these traitors had to be arrested and their wealth confiscated for the good of the people. After planning an insurrection, Hidalgo rang the church bells on September 16, 1810, and called upon the local Indigenous people and mestizos to rebel. The insurgent movement-turned-mob soon overtook Atotonilco—where Father Hidalgo presumably picked up the banner of Guadalupe—San Miguel, and Celaya, encountering its first significant opposition from the Spanish army in Guanajuato.

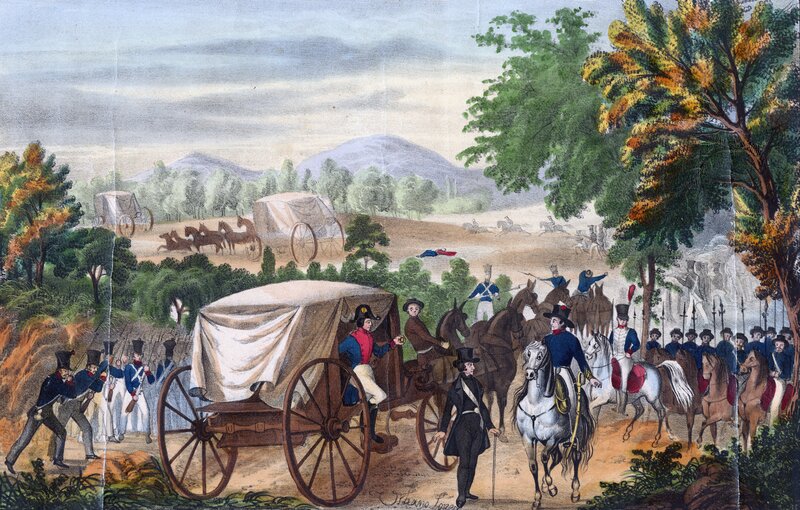

Depictions of royal forces capturing, imprisoning, and executing Father Hidalgo and Colonel Ignacio Allende by lithographer Urbano López, circa 1811. In March 1811, royal forces overtook Hidalgo, Allende, and his rebel army in Monclova, Coahuila. Governor Manuel Salcedo took the insurgents to Chihuahua, where Allende and the other rebels were summarily executed as traitors. Protected by ecclesiastical immunity, Hidalgo underwent an Inquisition trial, which found him guilty of heresy and treason. The Church defrocked Hidalgo and released him to civil authorities, who executed him on July 31.

José María Morelos took the reins after Hidalgo and Allende, leading four campaigns against the royalist forces. The concepts of liberalism and nationalism were critical in uniting the Indigenous, Black, and Mestizo people with the Spanish under the common goal of independence. Thus, Morelos at one point ordered all provincial intendants and magistrates to free any slaves in their territories and limit Indigenous servitude in Spanish estates.

Royal forces eventually captured and executed Morelos in 1815. Seeing this as an opportunity to quell the territory-wide rebellion, Viceroy Juan Ruiz de Apodaca, instituted the following year the indulto, or a pardon for insurgent leaders, which led to a couple of years of relative peace in New Spain. However, pro-independence groups throughout New Spain continued to repel Spanish authority. In this 1816 letter, Antonio López de Santa Anna reports on such rebellion in Veracruz.

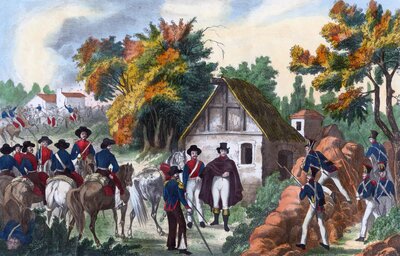

Depiction of the battle at the Hill of Barrabas near Zirandaro, Guerrero, by an unidentified artist, circa 1818. The insurgents, led by the General Chief of the Southern Troops, Vicente Guerrero, defeated General Jose Gabriel de Armijo's royalist forces.

On January 1820, Colonel Rafael de Riego rebelled in Andalucia, Spain, and demanded that Ferdinand VII swear on the Cadiz Constitution of 1812. Viceroy Juan Ruiz de Apodaca followed suit a few months later, surprising novohispanos; they feared that the viceroy’s proclamation suggested an incoming wave of liberalism, which would inevitably remove ecclesiastical and military privileges.

Viceroy Apodaca and Inquisitor General Matias de Monteagudo, eventually formed a conspiracy to make New Spain independent. When insurgent leader Vicente Guerrero learned of this, he attempted twice to recruit José Gabriel de Armijo, general of the royalist forces. This would be to no avail as Armijo later resigned due to differences with the viceroy.

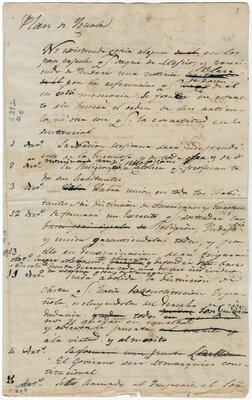

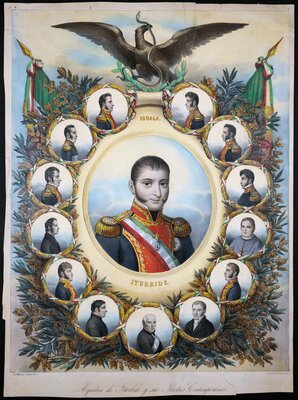

On November 1820, Viceroy Apodaca named Agustin Iturbide as Armijo’s replacement. Iturbide’s first assaults against Guerrero’s armies were not successful. He eventually acknowledged that independence could only be achieved if the royalists joined the insurgents. In February 1821, Iturbide met with Guerrero and drafted the Plan of Iguala, which Armijo later joined to lead one of the factions in the Army of the Three Guarantees.

Soon after forces coalesced, Spanish military leaders deposed Viceroy Apodaca, who was replaced by Juan O’Donoju. However, the inevitable finally occurred on August 1821: Iturbide met O’Donoju and convinced him that the Spanish attempt to control the insurgents was futile. The new viceroy signed the Treaty of Cordoba, which ended the War of Independence and recognized the sovereignty of Mexico.

Bibliography

UTEP Archival Collection: Escajeda family papers, MS556