Enforcing the Status Quo

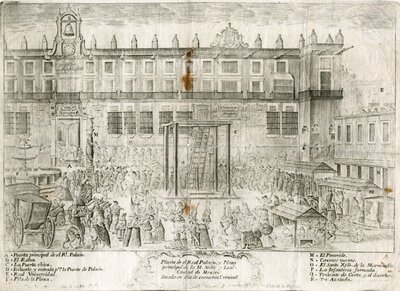

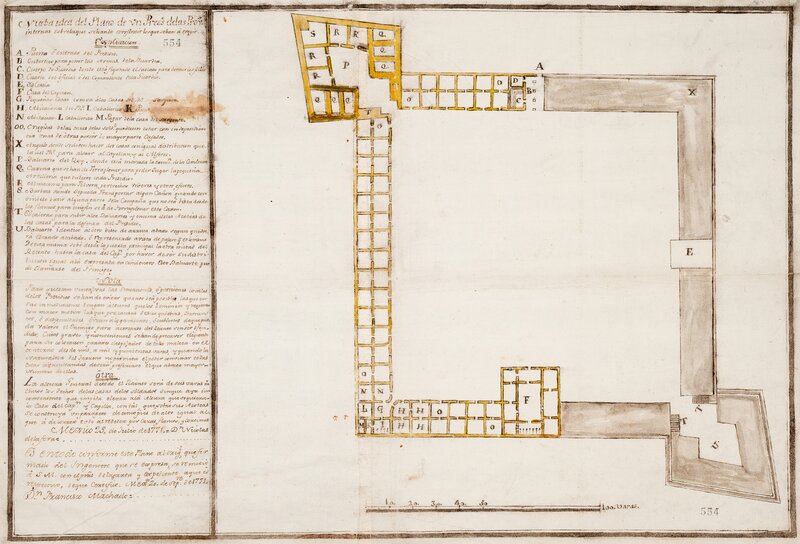

"Plan of the Royal Palace and Main Plaza of the Very Noble y Loyal Mexico City taken on the day of criminal execution" by an unidentified artist, 1780.

A Bureaucratic Society

The Spanish Crown installed a complex bureaucracy throughout its territories to maintain and enforce the status quo. Considering the extraordinary documentation it produced, scholars have argued that the empire essentially "ran" on paper. Besides regulating these bureaucratic processes, the Crown also sought to profit from them. From 1636 onward, it required the use of stamped government paper, or papel sellado, for all transactions and royal communication taking place in its overseas possessions. Depending on its use, the price for stamped government paper ranged from one-quarter real to twenty-four reales—all revenue that would feed royal coffers. The C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department of the University of Texas at El Paso Library preserves numerous examples of papel sellado in several of its collections.

Internal & External Threats

Even though the Spanish had conquered much of central Mexico by the mid-sixteenth century, the periphery proved to be an ongoing battle until the end of the colonial period. Many Indigenous communities in the northern region of New Spain continued to repel Spanish dominance. Among these were the nomadic and semi-nomadic groups collectively identified as the "Chichimec" (1554-1591), the Tepehuán, Pima, Seri in New Biscay (1687-1695), and the Pueblo people in New Mexico (1680-1694).

In the late seventeenth and throughout the eighteenth century, Spain also had to increasingly defend its territorial claims from other empires. The French were perhaps the most adamant in their incursion of New Spain, starting with French corsairs attacking in Veracruz (1683), Campeche (1685), and Yucatan (1689-1699). However, the French Crown's official and perhaps most threatening move was when it sought to establish settlements in New Spain's northern borderlands (1685-1686 & 1693-1719). The English also sought to penetrate the viceroyalty, but in the southern frontier, seeking to occupy points in Nicaragua (1673-1675, 1780), Campeche (1703-1719) and Belize (1722-1737).

To quell internal rebellion and keep foreign incursion at bay, the viceregal government erected forts throughout the periphery and financed a military force.

Policing the Urban Centers

The viceroyalty's urban centers, especially those with strong ties to the mineral extraction industry, experienced their fair share of lawlessness and rebellious behavior. In 1716, royal authorities created a law enforcement agency, the Tribunal of the Acordada, to address rural banditry. Seeing a rise in crime in the cities, municipal authorities started to reform and expand antiquated policing measures. However, it was not until mid-century that the Spanish Crown allowed the acordada force to assist in the cities' law enforcement.

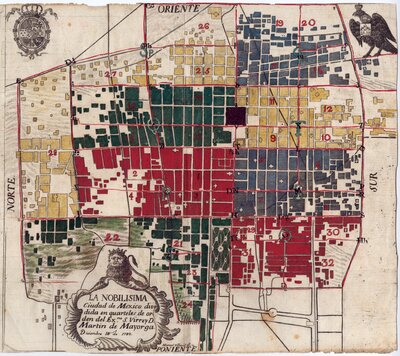

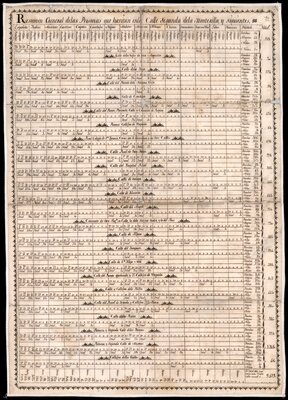

In an attempt to make policing of cities more efficient and keep a closer eye on urban grumblings, metropolitan officials started implementing the cuartel, or quarter, system in 1783 as another element of the vast Bourbon Reform program. This system divided cities into neighborhoods and placed a royal authority at its helm to maintain law and order. As seen in this map, authorities divided Mexico City into eight main cuarteles, dividing these further into thirty-two subunits. Alcaldes de barrio, or neighborhood mayors, not only maintained order in their assigned area, but also social control by keeping a detailed census of who lived in the smaller cuartel, similar to the one seen here.

Expulsion of the Jesuit Order

The Bourbon Crown also sought to reign in the power the religious orders held in New Spain and throughout the empire. Since the sixteenth century, these institutions had forged strong financial, educational, and familial bonds that afforded them significant influence over novohispano society. Feeling threatened, these religious fraternities, particularly the Jesuits, pushed back against Bourbon Reforms aimed at subordinating the Spanish Catholic Church under royal authority. When urbane rebellions erupted as a result of other reforms, the Bourbon Crown saw it as an opportunity to frame the Jesuit Order as inciter, expelling its members from the empire in 1767.

Novohispano society was shocked when they learned of the order's expulsion, to say the least. Around 1773, someone memorialized the "incredible" act by documenting the events. Many in New Spain still lamented the loss of the Society into the nineteenth century. In 1816, Manuel Quiros y Camposagrado composed a collection of poems yearning for the restauration of the religious order and dedicated it to Ferdinand VII.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Haslip-Viera, Gabriel. Crime and Punishment in Late Colonial Mexico City, 1692-1810. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Kuethe, Allan J., and Kenneth J. Andrien. The Spanish Atlantic World in the Eighteenth Century: War and the Bourbon Reforms, 1713-1796. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | MacLachlan, Colin M. Criminal Justice in Eighteenth Century Mexico; a Study of the Tribunal of the Acordada. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.