The Power of Indigenous Blood

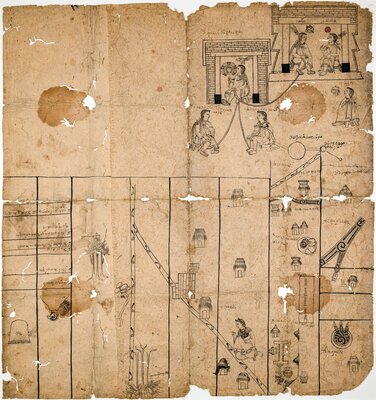

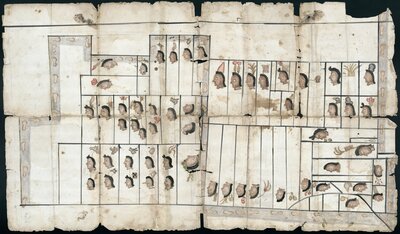

Map of Teozacoalco (present-day San Pedro Teozacoalco, Oaxaca, Mexico) and its subject towns by an unidentified Indigenous artist, 1580. The author included a diagram of the ruling Mixtec elite's lineage on the left side of the painting, which originated at the town of Tilantongo. "Tilantongo (present-day Santiago Tilantongo, Oaxaca, Mexico) was the source of many ruling Mixtec lineages, so the ruling family of Teozacoalco used their Relación Geográfica map to document the connections" (Mundy, 115).

After the European invasion, the Indigenous nobility "continued to occupy an important place in the colonial world” (Benton, 165). Bringing Indigenous power structures under the Spanish fold, the Crown bestowed upon local elite economic privileges, such land holdings and tribute exemptions, and titular rights. To maintain their authority and identity as descendants of pre-conquest rulers, Native elites meticulously documented their ancestry, creating richly illustrated genealogies. Practically, these depicted lineages would serve as key evidence in colonial courts when threats emerged to their wealth and status. Symbolically, these documents embodied a longing of these Indigenous elites to identify themselves as conquerors rather than conquered.

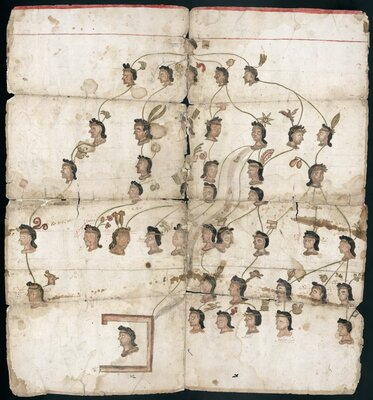

Considering the rights and status that ancestral connections with royal Indigenous blood conferred, genealogical diagrams often surfaced when there was a power vacuum. Such was the case when Apostolic Inquisitor and Bishop of Mexico, Fray Juan de Zumárraga, condemned Acolhua noble Don Carlos Chichimecateuctli to the stake in 1539 for idolatry. This truncated the widely accepted lineage of famed ruler Nezahualcóyotl—the tlatoani of Tetzcoco, one of the three ruling city-states in the Nahua Triple Alliance. The execution of his grandson resulted in the emergence of competing claims to the royal bloodline and throne.

This document represents one of these competing families. In it are three genealogical diagrams that tie back to Nezahualcóyotl, who is identified with a coyote-head glyph throughout. An unidentified wife of his is the focus of the top-left family tree, and his son and heir to the throne, tlatoani Tepiziatzin, is central to the top-right drawing. Both of these connect to the central circular genealogy of Mixtecatzin—the ancestor of the litigating family. To explore this genealogy, visit the annotated version in Pelagios' Recogito.

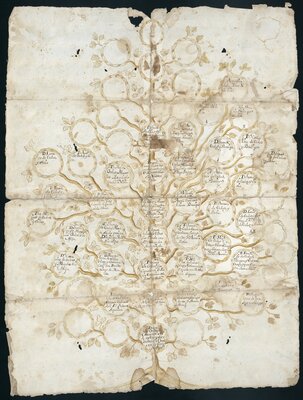

Ancestral ties to Indigenous rulers who fought on the side of the conquistadors continued to be relevant at the end of the colonial period. For example, a distant descendant of Chimalpopoca, the tlatoani of Tacuba, created this family tree in the eighteenth century to prove their nobility. During the conquest, Chimalpopoca sent three hundred warriors with Cortés' faction to subjugate the city-states of Toluca and Tarasquillo. For his service, Philip II awarded the ruler and his descendants with a coat-of-arms and special privileges. Noting their ongoing lawsuit against Don José Cortés Chimalpopoca (top-right tree branch), who was recognized as a legitimate descendant of the king, the author likely diagramed this lineage to claim some of these privileges and noble status.

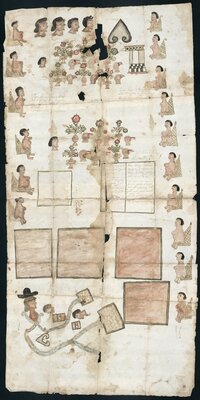

Indigenous elites often presented genealogical diagrams as evidence in viceregal courts to support land claims. They appended them to maps to prove their connection to pre-conquest nobility and thus their right over the territory in question. For example, a litigant presented this schematic map with a lineage that connected them to Tlaxcalteca noble Ocelotzin, who the artist identified with a jaguar head glyph on the top-right.

The importance of parentage originating during the conquest period in land disputes continued well into the eighteenth century. In some instances, nobles claimed descent to both Indigenous rulers and the conquistadors. Such was the case for Doña Sebastiana de Ordaz, the cacica, or Indigenous leader, of Tepejojuma. When the Hospitaller Order of the Brothers of Saint John of God convent requested access and rights over the waters of the Tlayanala and Chalma rivers and a nearby ranching estate, Doña Ordaz took them to court claiming that the territory was part of her cacicazgo. Her husband, Cristóbal Chacón, submitted on her behalf these genealogical and territorial paintings (below) to prove that she was the descendant of Maxixcatzin—the Tlaxcalteca tlatoani of Ocotelolco—and conquistador Don Diego de Ordaz, both of which served the Spanish Crown during the invasion of the Americas.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Benton, Bradley. The Lords of Tetzcoco: The Transformation of Indigenous Rule in Postconquest Central Mexico. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Boone, Elizabeth Hill, and Tom Cummins, eds. “Native Traditions in the Postconquest World: a Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 2nd through 4th October 1992.” Washington, D.C: Dumbarton Oaks, 1998.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Douglas, Eduardo de J. In the Palace of Nezahualcoyotl : Painting Manuscripts, Writing the Pre-Hispanic Past in Early Colonial Period Tetzcoco, Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010.

Resource | Hernández Rodríguez, Sonia Angélica. “Dos Versiones de un documento: Genealogía del Calpulli de Huitznahuac vs. Genealogía de Francisco Cortes”. In Tetlacuilolli. https://www.tetlacuilolli.org.mx/.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Himmerich y Valencia, Robert. The Encomenderos of New Spain, 1521-1555. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Rubio Mañé, J. Ignacio. El virreinato. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, UNAM, 1983.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Mundy, Barbara E. The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.