Spatial Colonization

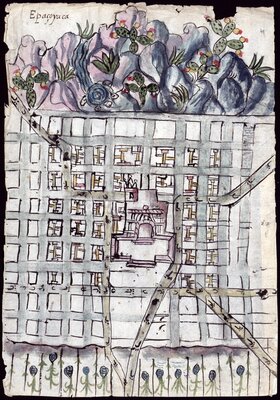

Map of Cholula and its neighborhoods by an unidentified Indigenous artist, 1581. The Indigenous council hall, the Franciscan missionary complex—the San Gabriel convent, church, and Indigenous chapel—and the royal administrator’s house enclosed Cholula’s plaza, where the tianguis, or open-air market, would take place.

The Crown considered the Americas a tabula rasa, or a clean slate, on which they could reconceive Spanish society through spatial planning. Hoping to avoid the organic development of European towns, colonial authorities implemented a grid plan based on Renaissance principles to “order” space. At the center was a plaza, which served as the principal social, economic, and religious space.

Buildings representing the colony’s three forces—the Crown, the Catholic Church, and the economy—defined the main square. The convent or parish church would typically line the east side of the plaza. It would also dominate the town's architectural landscape, as seen in the sixteenth-century painting of Epazoyucan (in the modern state of Hidalgo, Mexico): the artist only drew the Augustinian Church of San Andrés Apóstol, centering it on the composition.

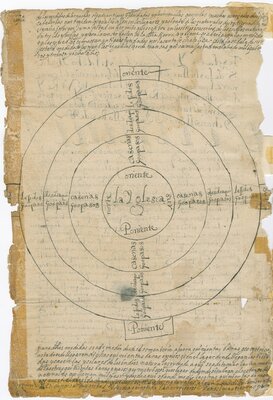

Counterbalancing the Catholic Church and representing the royal government, the municipal hall would typically make up the west face of the plaza. Lining the other sides of the square were structures for commercial activities. The houses of the Spanish and Indigenous elite, as well as any secondary churches or shrines, would then complete and radiate from this architectural core. Lastly, housing for those who did not belong to the elite classes, larger estates, and agricultural land formed the town’s periphery, as seen in this diagram.

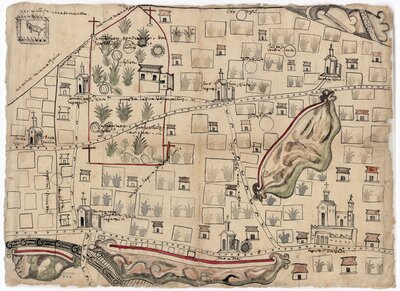

Map of "the most noble, and very loyal City of Angels", or Puebla, Mexico, by an unidentified cartographer, 1754. As towns turned into cities through the centuries, the colonial grid plan continued to define the urban sprawl.

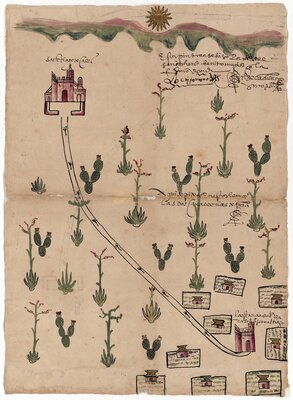

Beyond the grid plan, the Spanish also implemented regional spatial hierarchies. They subjugated smaller settlements under the authority of larger towns known as cabeceras, or district heads, to coordinate colonial rule and extraction, as this painting of Acapistla illustrates. As they restructured or reinforced existing spatial relationships, they also colonized the communal identity of Native city-states: They prefixed the Indigenous names of towns with Catholic saints' names, giving these preference in official documentation. As art historian Barbara Mundy noted, “renaming was even more violent by being alphabetical instead of visual as the Aztec had accommodated” (Mundy, 166-167).

The land in between these settlements was eventually also colonized. Initially, few conquistadors pursued land grants, focusing their petitions on obtaining control over Indigenous labor. During the first half of the sixteenth century, the Crown had adopted and encoded into law the philosophical and legalistic understanding that the Spanish could not dispossess the Indigenous of the lands they occupied. However, as epidemics ravaged the population and labor became scarce, encomenderos and Spaniards who were not able to secure encomiendas set their sights on communal landholdings that lied fallow (Owensby, 16). Considering them "vacant" and unowned, the colonizers started to claim them as agricultural or grazing lands for livestock.

To prevent the encroachment and expropriation of Native territory, the royal government attempted to regulate the land grant process and set spatial limits, as seen in this diagram. First, royal officials would make a proclamation of newly presented land petitions. An investigation to ascertain that requested land grants would not dispossess nor affect nearby Indigenous communities would then follow. During this time, Natives could oppose and negotiate with Spanish and Indigenous land petitioners to protect their fields and water sources, with both parties creating painted maps as evidence of their claims (Pulido, 79-83).

Hand-painted maps of the Tepexi de la Seda province by an unidentified Indigenous artist, 1584. The Native leaders of Tepexi (present-day Tepexi, Puebla, Mexico) commissioned this paintings to include in legal proceedings they submitted against the grant of two sites and two caballerias Doña Alonsa de Sande requested. To learn more about this case, and to contribute to its transcription, please visit the University of Texas Libraries' FromThePage platform.

As colonizers propagated northward (present-day northern Mexico and the American Southwest), they mostly encountered semi-nomadic or nomadic nations who typically did not welcome the Spanish encroachment. Their first colonizing act was to forcefully congregate them in specific areas to "pacify" them in formally established towns. In this report to the viceroy, Lieutenant Colonel Diego Ortiz Parrilla described his efforts to settle and "extinguish" the rebellions of the Seri, Tiburon, Salinero, and Tepoca nations in present-day Sonora, Mexico. By geographically anchoring these Native communities, the Spanish sought to facilitate indoctrination and the extraction of Indigenous labor and resources.

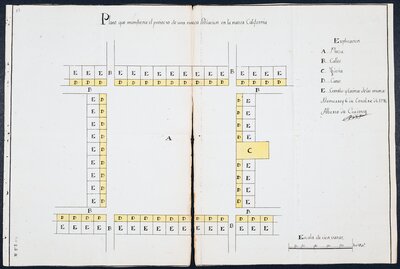

Much like they had done in the Valley of Mexico, the Spanish would then implement a grid plan in these newly formed settlements to represent colonial power spatially. As this schematic diagram of a proposed settlement in California demonstrates, the Spanish continued to underscore the importance of the plaza in colonial society, placing it at the heart of frontier communities. The church would again punctuate the space with houses marking the boundaries of the plaza. Roads would then radiate out from the square's corners to perpetuate the established grid plan.

Claiming territory and marking out land ownership around these town cores was equally important in the frontier. The C. L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department at The University of Texas at El Paso preserves a rare land deed petition that clearly evidences the Spanish desire to possess land. In this document, Juan Andrés de Ávalos, a resident of the Our Lady of Guadalupe pueblo at the pass of the River of the North (present-day Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico), requested an official deed of land ownership.

According to the record, Domingo Misquía, captain at the royal Presidio of Our Lady of the Pillar, had gifted Ávalos a plot of land on the occasion of his marriage to the former's niece, Ascensión Jurada de Gracia y de la Rosa Misquía. In the petition, Ávalos provided detailed measurements of the plot and the names of neighbors to clearly demarcate the his property. To learn more about this document, and to contribute to its transcription, please visit the University of Texas Libraries' FromThePage platform.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008.

UT Catalog | Lindsay, Mark. “Urban Planning Characteristics In 16th Century Yucatan: ‘Regular’ Grids For Idealized Repúblicas.” The Latin Americanist (Orlando, Fla.) 48, no. 1 (2004): 45–58.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Mundy, Barbara E. The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Nemser, Daniel. Infrastructures of Race: Concentration and Biopolitics in Colonial Mexico. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2018.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Owensby, Brian Philip. Empire of Law and Indian Justice in Colonial Mexico. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Worldcat | Pulido Rull, Ana. Mapping Indigenous Land: Native Land Grants in Colonial New Spain. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2020.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Wagner, Logan, Hal Box, and Susan Kline Morehead. Ancient Origins of the Mexican Plaza: from Primordial Sea to Public Space. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013.

!["Registro y posesión de [tierra de] Juan Andrés de Ávalos", página 1](https://exhibits.lib.utexas.edu/images/1300/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)