Mexico's North Star

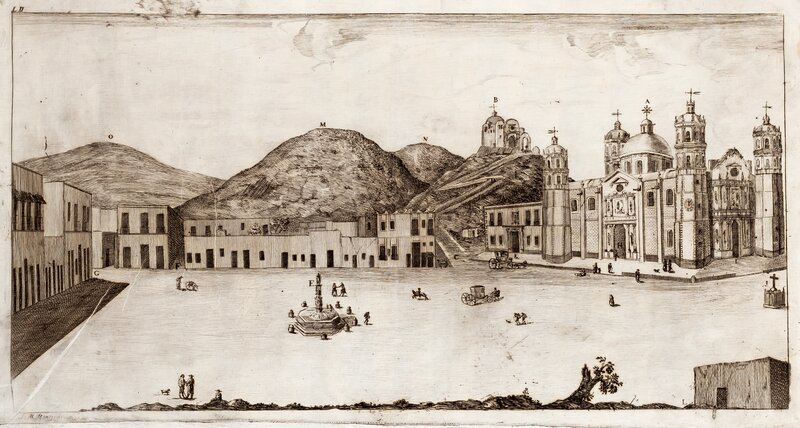

Perspective view of the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the sixteenth-century shrine atop Tepeyac Hill, and its surroundings by Bonnard, undated. Throughout, the artist marked the places where Our Lady of Guadalupe miraculously appeared before Juan Diego in 1531 at Tepeyac Hill. At the top-center of the composition, Bonnard placed an ornate cartouche held by two cherubim that depicts the scene where Juan Diego reveals the miraculous impression of Our Lady of Guadalupe on his cloak to the Bishop of Mexico, Fr. Juan de Zumárraga.

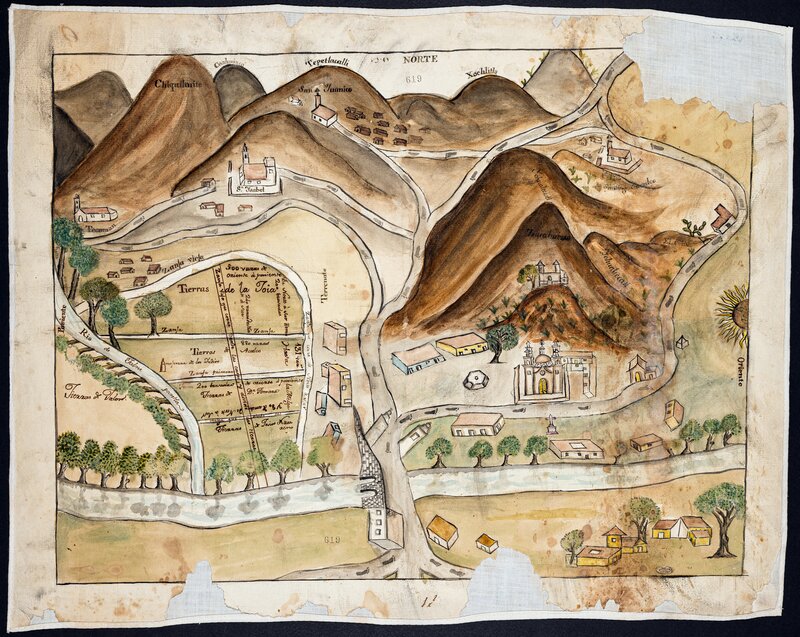

Indigenous pilgrims often referred to Our Lady of Guadalupe as Tonantzin, the mother of the Nahua pantheon, in the second half of the 16th century. For many natives, this reference made Christianity more understandable and relatable. However, this association was problematic for Franciscan friars, claiming that it promoted idolatry. Despite the pushback, many mendicant friars and clergy embraced the symbol as a potent Christianizing force.

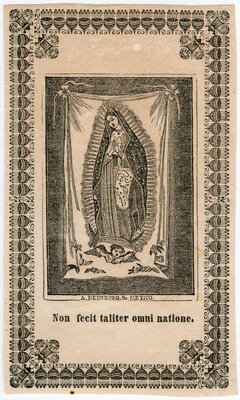

Most of what is known about the origins of the Virgin of Guadalupe story is preserved within the pages of two books published in the 17th century. Miguel Sánchez authored the earliest account of Juan Diego and the apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe in 1648 in the Imagen de la Virgen María, Madre de Dios de Guadalupe. Some have argued that creoles promoted the rise of the Virgin of Guadalupe cult, framing it as a uniquely American symbol that gave fuel to Mexican patriotism. Until this day, the Virgin of Guadalupe continues to be the “Morning” or “North Star” that unites Mexicans under a shared identity.

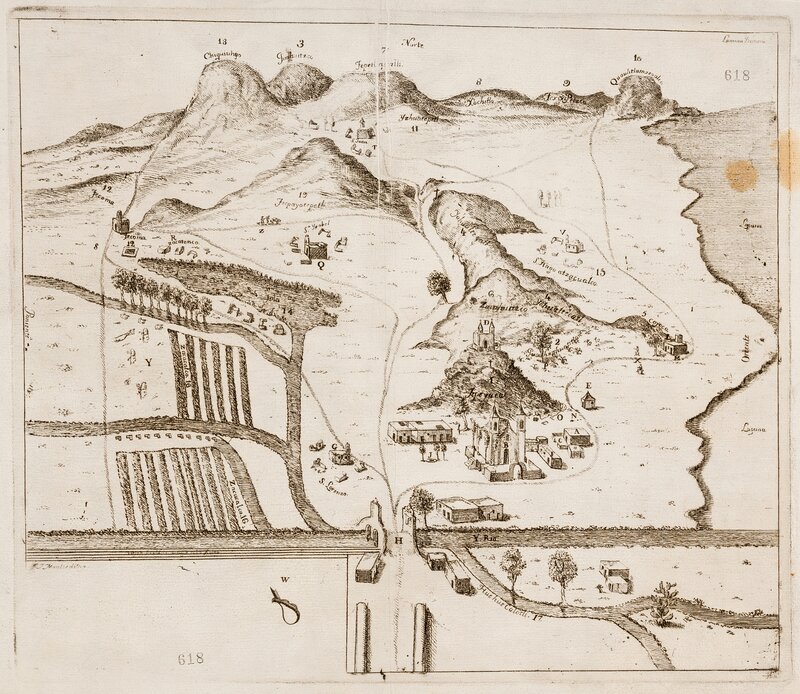

The original shrine, constructed as early as 1568, sits at the top of the Tepeyac Hill. Unlike most churches, the shrine was not razed to create a new structure. A second building was erected at the bottom of the hill in 1622. When the devotion became widespread after Miguel Sanchez’s 1648 retelling of the legend, the shrine became a destination point for a significant inflow of pilgrims. To accommodate the influx, a basilica was constructed next to the 1622 building at the turn of the eighteenth century.

Prints such as this one were created and distributed among the pious to raise funds for the construction. This was a long-standing practice: in 1615, Flemish engraver Samuel Stradanus printed images of Guadalupe’s miracles to solicit donations for the second building completed in 1622. The same was done to construct the Chapel of El Posito, which marked the spring where Juan Diego spoke with Our Lady of Guadalupe.

The chapel was entirely built through donated labor. Fray Juan Antonio Sánchez Alocén, the inaugural Bishop of Linares in Nuevo León and a Descalced Franciscan friar, granted 40 days of indulgence, or a reduction or absolution of punishment one would have to undergo for sin, for any individual who contributed their labor to the construction of the chapel. Dr. Alonso Núñez de Haro y Peralta, the Archbishop of Mexico, also issued 80 days of indulgence for those who labored in the construction. Starting in 1777, the construction for the small structure ended in 1791.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Brading, D. A. Mexican Phoenix : Our Lady of Guadalupe : Image and Tradition Across Five Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.