The Lettered City

Interior perspective of the "Sumptuous Library of the Distinguished Palafoxiana Seminary of Puebla de los Ángeles" by artist Miguel Jerónimo Zendejas (1724-1815) and engraver José de Nava (1735-1815), 1773. This print was made in commemoration of the library's grand opening and dedication.

Although doctrinal and linguistic texts for the "spiritual conquest" dominated the colonial literary output, New Spain's lettered elite also produced and consumed writings on a variety of topics. These included astronomy, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, theology, history, and literature, among others. To see some examples, visit the Primeros Libros de las Américas project.

Through the centuries, manuscript and printed books often served as weapons in ideological battlegrounds. Early on, Europeans authored treatises on the humanity of the Indigenous people as they debated their place in Spanish Catholic society. Seeking to participate in this argumentation, Nahua and mestizo intellectuals, such as Juan Buenaventura Zapata y Mendoza and Juan Bautista Pomar, wrote local Indigenous histories to frame their ethnic identity as a contribution to the empire. Embracing this Indigenous scholarship, Creoles, or American-born Spaniards, used it to counter the prevailing thought that they were less rational than peninsulares, or Iberian-born Spaniards, because of the American climate. Below are a few examples that demonstrate how novohispano cultural unfolded in intellectual productions.

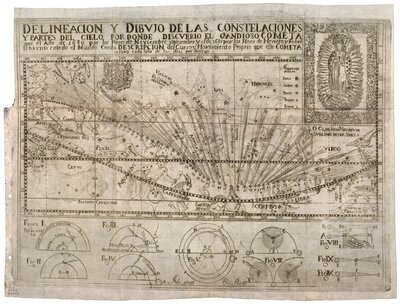

Indigenous and European cultures often looked to the skies to make sense of their place in time and space. A particular star—Kirch's Comet—would divide Mexico’s lettered elite when it crossed the American skies in 1680. Traditional European and Indigenous beliefs alike considered comets bad omens that most often foretold a ruler’s death, war, or famine.

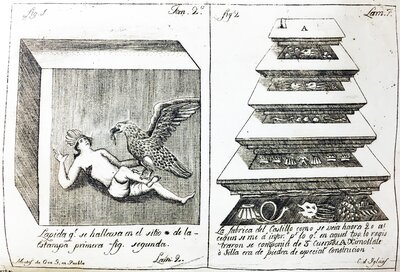

Attempting to appease the masses, creole polymath Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora wrote the polemic Philosophical Manifest against the Comets (1681) to demystify these celestial bodies. In defense of conventional thought, Eusebio Francisco Kino, an Italian Jesuit principally known for his missionary work in California, wrote Astronomical Exposition of the Comet (1681) and illustrated therein the comet’s trajectory seen here. However, underlying this public confrontation was the belief that creoles were intellectually and morally deficient due to their birth or upbringing in the “hot and humid” Americas.

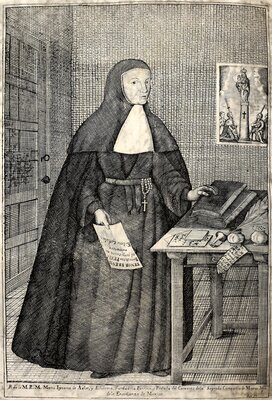

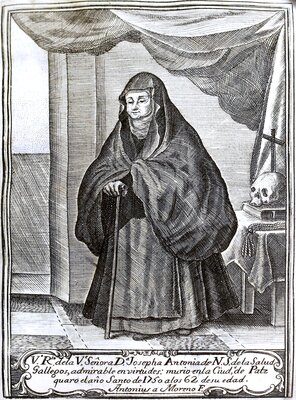

Despite social constraints, nuns contributed greatly to colonial literature. These cloistered women wrote convent chronicles, diaries, poetry, plays, and devotional literature. During the seventeenth century, biographies of "exemplary" nuns, like the ones shown here, emerged as a popular genre. These books highlighted the work of leading women who had mystical experiences, established convents, or educated novohispano youth.

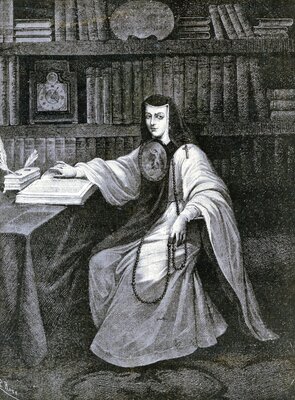

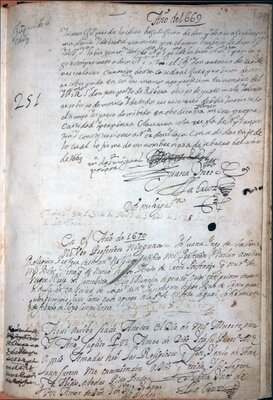

Perhaps the most well known was Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz, a creole. Not quite living up to her 1669 religious vows to live a life in obedience, poverty, and perpetual cloister, she actively participated in New Spain’s intellectual debates. Hailed as the “Tenth Muse” by her contemporaries, she countered—with her life and writings—Europeans’ negative perceptions of American-born Spaniards.

Spanish patriarchy and misogyny would eventually quell Sister Juana’s outspokenness when she critiqued a sermon by Jesuit António Vieyra in 1690. Admonished by the Archbishop of Mexico for trying to engage in a theological debate, she receded from public intellectual discourse and dedicated herself to the care of infirm sisters in her convent. Ever the poet, she renewed her religious vows at the end of her life (seen here) and signed them with her blood, hoping that it would “all spill in defense of the Holy Faith” for she was “the worst in the world.”

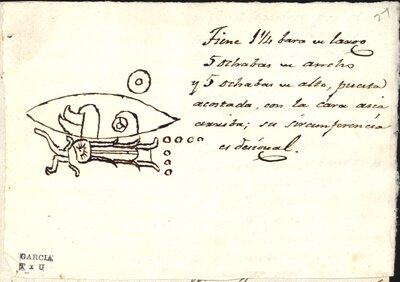

During the eighteenth century, intellectuals started to revisit the colony's pre-conquest history and cultures. Shunning written and oral Indigenous histories, European scholars primarily turned to the artifacts and ruins, or "objective evidence", excavators were uncovering in archaeological sites. A retired military captain, Guillermo Dupaix, was among these early antiquities explorers. With Charles IV's sponsorship, Dupaix surveyed and excavated throughout New Spain from 1805 until 1809. His archaeological descriptions and the drawings of his cavalry escort, José Luciano Castañeda, would garner significant attention from a European audience eager to "rediscover" and reinterpret America's ancient past.

Many of these scholars amassed great collections of books. Among these was Bishop of Puebla and interim Archbishop of Mexico, Juan de Palafox y Mendoza. In 1646, he donated over five thousand volumes to the San Pedro y San Juan seminaries in Puebla, Mexico. This collection would eventually become the Palafoxiana, which is often considered the first ‘public’ library in the Americas. Explore the operations of the Palafox Library at the end of the eighteenth century below or click here to open this project in a separate tab.

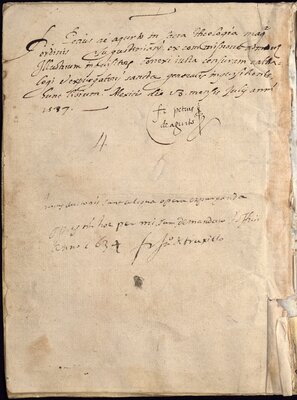

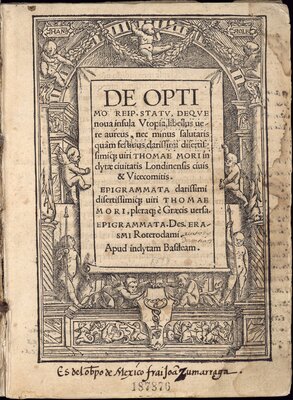

As seen in Sister Juana's case, the colony's intellectual life would not go unchecked. The Spanish Crown established the Holy Office of the Inquisition to surveil and maintain orthodoxy in New Spain. Part of this work entailed the inspection of libraries and books. Inquisition agents scrutinized imported and questionable works, regardless of who authored or owned them. For example, the Inquisition had its book censor, Augustinian friar Pedro de Agurto, examine the first Bishop of Mexico Juan de Zumárraga's copy of Thomas More's De optimo. The mendicant left notes on its margins and struck through numerous parts of the text as part of his review. From these book reviews and those coming from the Iberian Peninsula, the novohispano Holy Office also published indexes of banned books. Inquisition officials would post these lists in public places for all to read with the expectation that those in possession of these prohibited imprints would hand them over for either censorship or destruction.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Arias, Santa, and Raúl Marrero-Fente. Coloniality, Religion, and the Law in the Early Iberian World. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2014.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Cañizares-Esguerra, Jorge. How to Write the History of the New World: Histories, Epistemologies, and Identities in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2001.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Chowning, Margaret. Rebellious Nuns: The Troubled History of a Mexican Convent, 1752-1863. London: Oxford University Press, 2006.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Lavrin, Asuncion. Brides of Christ: Conventual Life in Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | McDonough, Kelly S. The Learned Ones : Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. Tuczon, Arizona: The University of Arizona Press, 2014.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Sampson Vera Tudela, Elisa. Colonial Angels : Narratives of Gender and Spirituality in Mexico, 1580-1750. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Sánchez Prado, Ignacio M., Anna M. Nogar, and José Ramón Ruisánchez Serra. A History of Mexican Literature. New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Socolow, Susan Migden. The Women of Colonial Latin America. West Nyack: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Villella, Peter B. Indigenous Elites and Creole Identity in Colonial Mexico, 1500–1800. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.