Exploitation of Indigenous People

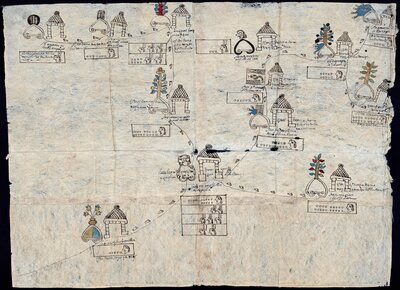

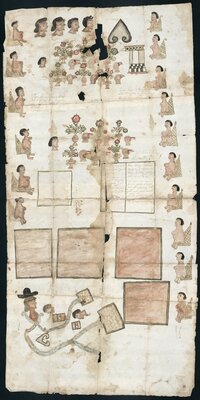

Hand-drawn map of Muchitlan (present-day Mochitlán, Guerrero, Mexico) and its surrounding subject towns by an unidentified Indigenous artist, 1582. The artist represented each community with a town hall drawing and its Indigenous logogram. Near the two symbols, a square indicates the number of tributantes, or Indigenous households paying tribute to encomenderos, residing in the town.

“The Spaniards do not have other ways of profiting nor sustaining themselves in [New Spain] except with the help they receive from the Natives...[without their help] they will not be able to survive...[and] will have to leave the land...[and] Our Lord God and Your Majesty will lose their service." — Letter from Hernán Cortes to Emperor Charles V, 1524

From the onset, the conquistadors sought as their reward control over the Indigenous people to enrich themselves. They implemented in Mexico the encomienda system, a continuation of the pre-conquest tribute and labor system with a redistribution of its benefits to the colonizers (Lockhart, 28). Considering the Natives "free subjects", the Spanish Crown explicitly forbade the conquistadors from establishing the servitude model. However, they managed to exact the "reward" with the veiled threat that they would pack up their bags and abandon the colonial enterprise. Ceding, the monarchy demanded that the encomenderos provide for the indoctrination of the Natives in exchange for their labor and tribute.

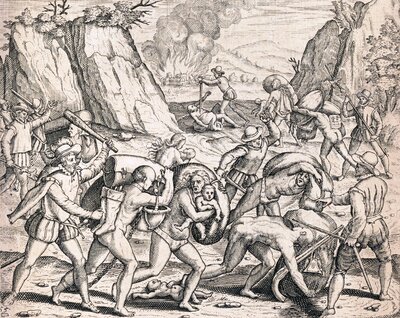

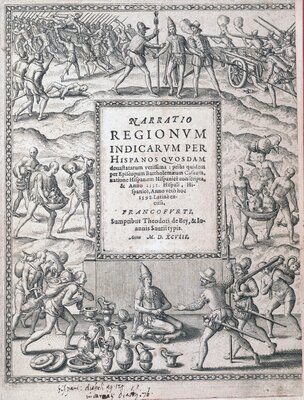

Engraved depiction of enslaved Indigenous people in Dominican Fr. Bartolomé de las Casas' Narratio regionum Indicarum per Hispanos quosdam deuastatarum verissima by Joos van Winghe, 1598. The friar claimed that conquistador and Audiencia of Mexico president Nuño de Guzmán enslaved over four thousand free men, women, and children in Jalisco. According to Fr. Las Casas, "the women, having just given birth, carried loads for the bad Christians; not being able to carry the infants due to the work and weakness from hunger, [the women] left them by the roads, where infinite numbers of [infants] perished."

Spanish exploitation of the Indigenous people ensued, especially after epidemics ravaged communities throughout the sixteenth century. A steep decline in the labor supply and tribute followed the demographic collapse, and the encomenderos sought to exact the same amount of resources from the dwindling population. Expectedly, this led to abuse: according to countless grievances, encomenderos would murder Native laborers by over whipping them or sell them to turn a profit.

Indigenous communities regularly submitted official complaints about the maltreatment they were experiencing. In a letter to the Bishop of Oaxaca, Philip II expressed concern about the Natives in the diocese. Word had reached him that the population was diminishing due to encomendero violence. Apparently, the situation was so dire that women would miscarriage from the loads they had to carry or "kill their children upon birth saying that they would do it to free them from the abuse that they suffered". All the king could really do was exhort the bishop to try to intervene and protect the Indigenous people in Oaxaca.

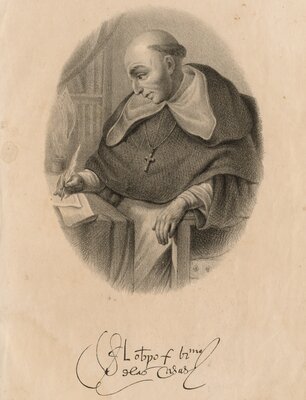

Tasked with the spiritual wellbeing of the Indigenous people, some mendicant friars tried to intercede. Perhaps the most well-known was Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas. An encomendero-turned-Native rights advocate, Fr. Las Casas wrote extensively to denounce the Spanish exploitation.

The Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (1552), a rhetorically graphic history on the Spanish invasion of the Americas, is perhaps Fr. Las Casas most impactful work. The book was published soon after his famous 1550-1551 debates with Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda and other renowned humanist scholars on the rights and treatment of the Indigenous people. Before the empire's intellectual authorities, Fr. Las Casas deftly argued against their prevailing claim that the Natives were subhuman due to their "crimes against nature", i.e. human sacrifice practices, and thus worthy of enslavement.

Fr. Las Casas' treatises and appeals to sovereigns to a certain extent bore fruit throughout his lifetime: influenced by his writings, Catholic Pope Paul III proclaimed the humanity of Native people in 1537. Five years later, Spanish emperor Charles V issued the "New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of the Indians", which sought to replace the encomienda with the repartimiento system, where royal officials allocated Indigenous labor (Himmerich y Valencia, 317). Unfortunately, both proclamations did little to assuage local abuse.

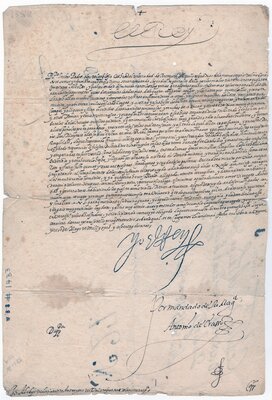

Spanish dependency on the Indigenous body never ceased. As this painting demonstrates, descendants of conquistadors continued to reap from the forced labor system well into the eighteenth century. This illustrated document details the tribute and labor obligations of the town of Tepeojuma towards Don Diego de Ordaz. Apparently, the Indigenous community had to send women and men weekly to work in the estate and deliver flowers, turkeys, and firewood every Sunday.

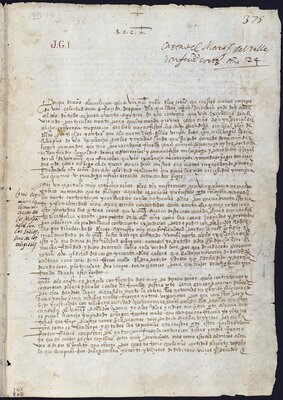

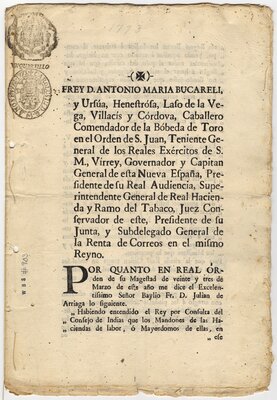

Exploitation also persisted. Continuing to receive pleas from Native communities, the Spanish monarchy repeatedly issued decrees like the one shown here barring violent excesses. In this eighteenth-century printed order, the royal Council of the Indies recounted news it had heard that hacienda superintendents were forcing Indigenous field hands to work from sunrise to sunset without letting them take a mandatory two-hour noon break. The Crown believed that the foremen were "treating [the Natives] as slaves, which [was] strictly forbidden by the laws." However, the council's order would fall on deaf ears for it often relied on the same local administrators perpetrating the abuse to enforce royal mandates.

Collaborative Transcription

Help the Benson Latin American Collection make its archives more accessible! Contribute by transcribing or correcting transcriptions of the documents below:

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Himmerich y Valencia, Robert. The Encomenderos of New Spain, 1521-1555. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Lockhart, James. The Nahuas after the Conquest a Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1992.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Owensby, Brian Philip. Empire of Law and Indian Justice in Colonial Mexico. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2008.