Illustrating Nobility

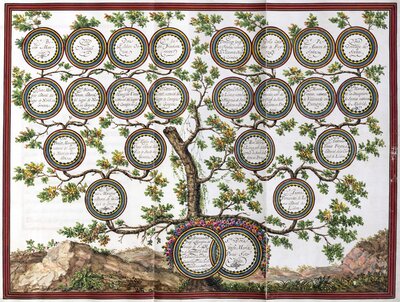

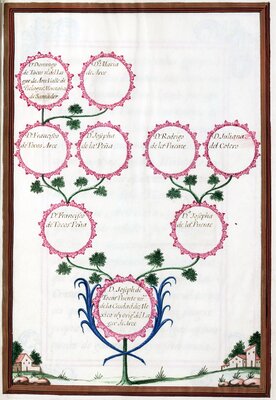

Don Fernando Jose Mangino’s family tree by an unidentified artist, 1793. The diagram illustrates his descendants and their place of origin as branches of a tree, culminating with him and his wife, Doña Josefa Maria Panes Soto Aviles. Don Mangino quickly ascended the ranks and held several titles in New Spain, ultimately returning to Spain in 1788 to serve on the Council of the Indies, the highest court overseeing the American territories. This family tree, along with a narrative description of the lineage, was created the year he ended his service on the Council.

Military service carried great weight when Spaniards and Indigenous rulers petitioned for nobility in Spanish colonial society. Heraldry, the system that governed the issuance and design of coat-of-arms for nobles, had military origins. Although the practice can be traced back to the Greco-Roman world (550-330 BCE), it became established custom in Europe during the Middle Ages (1300-1500 CE) as a way to recognize Christian knights for their military prowess during the Crusades: feudal lords bestowed onto knights heraldic designs that they could display publicly to denote their allegiance, honor, and noble rank in medieval society.

In early modern Spanish society (1500-1800 CE), a family’s contribution to the Reconquista, or the Catholic expulsion of Muslim rule from the Iberian Peninsula in the late fifteenth century, would often form the basis of many petitions for titular rights. After the invasion of the Americas, participation in the conquest would also emerge as another justification for obtaining the noble rank. In essence, colonial subjects proved their worthiness for obtaining social status and coats-of-arms to the Spanish Crown by underscoring their active role in the violence against non-Christian communities.

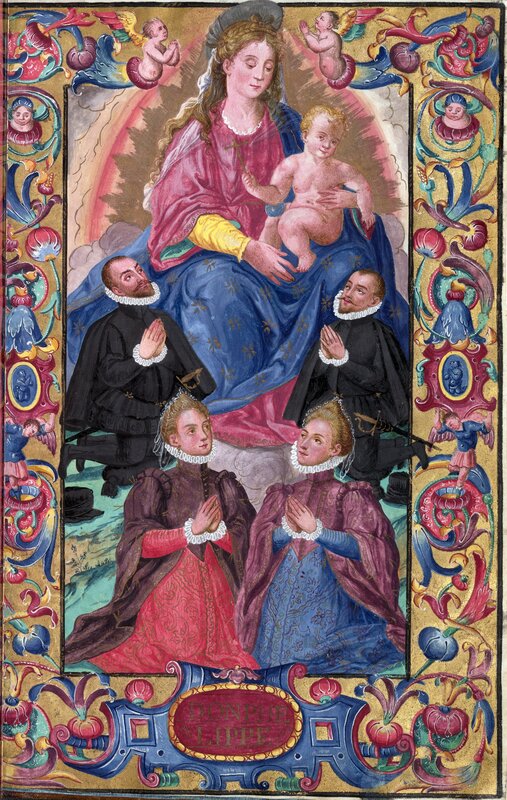

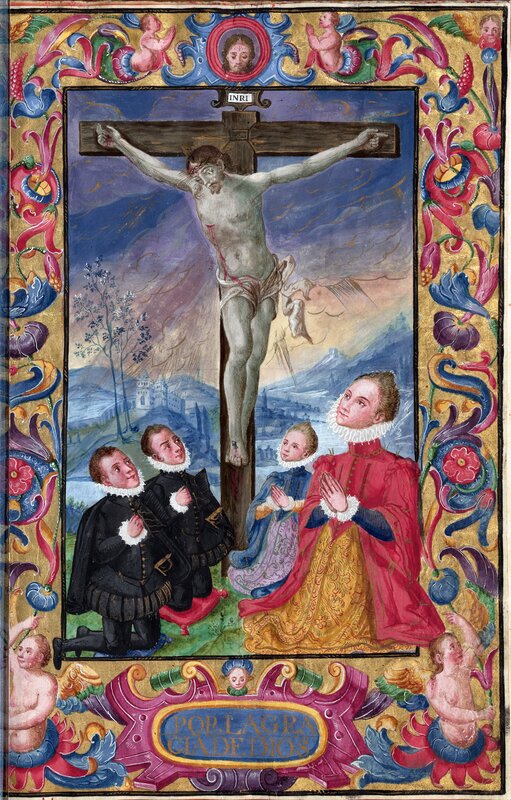

Framed paintings of Saint James, Madonna and Child, Christ on the Cross, and a coat-of-arms appended to the “legitimacy and blood purity” file of Ramón González Becerra by an unidentified artist, 1775. Spaniards had to prove “blood purity”—or the absence of Jewish, Muslim, and African ancestry in their lineage—to not only qualify for nobility, but also for religious and civic offices in New Spain.

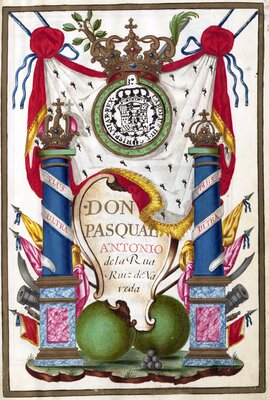

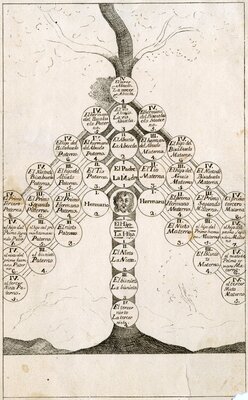

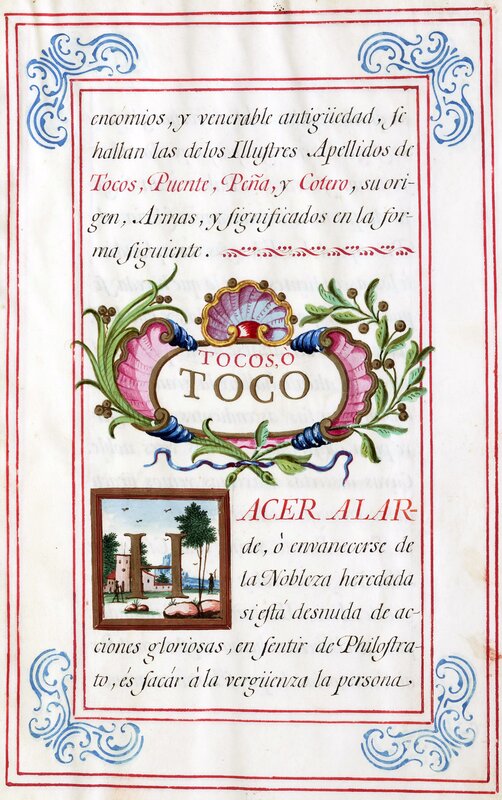

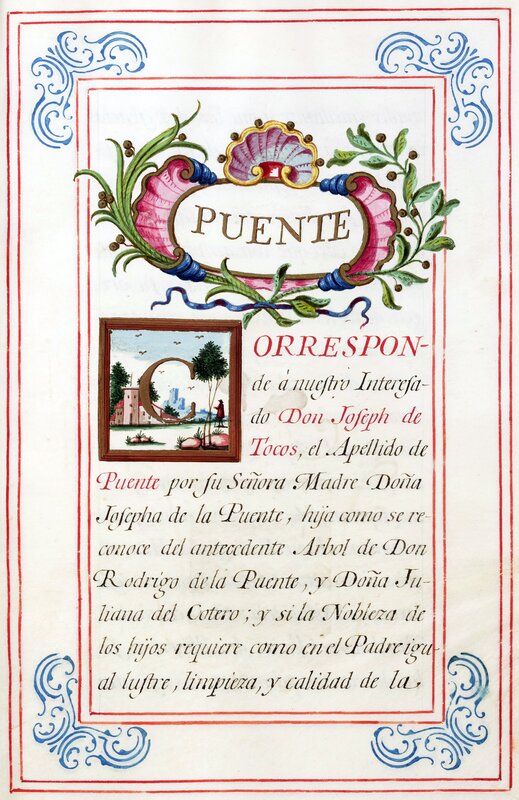

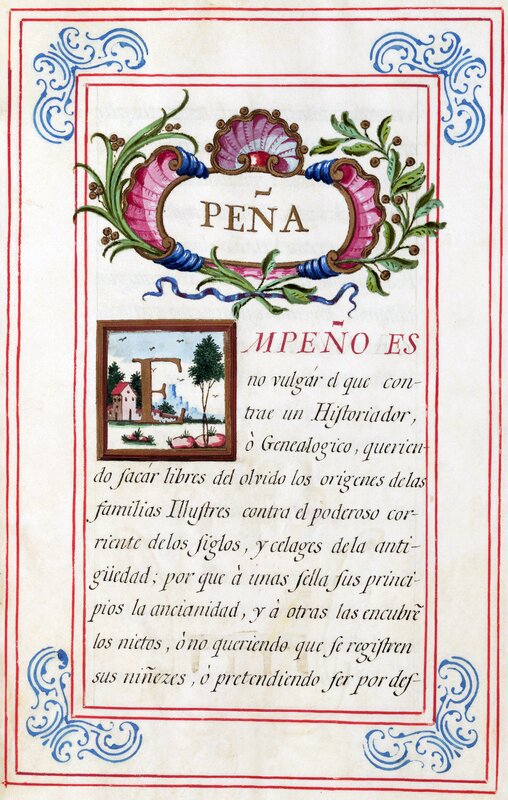

The influx of petitions from those involved in the Iberian Reconquista and American conquest led to the regulation of the practice to maintain the exclusivity of the noble class. To curb the unauthorized and “excessive” issuance of the rank throughout the empire, the Spanish Crown centralized the authority on “Chronicler and King of Arms” officials and codified the application process. Individuals who sought nobility had to submit a fully designed coat-of-arms, a genealogical tracing of the represented family names, a listing of their titles, and a justification for obtaining the rank.

Genealogy was central to the petition. The Chronicler and King of Arms would conduct genealogical research to scrutinize the family trees, confirm noble lineage(s), and certify the corresponding heraldic designs. Highly illustrated family trees, usually appended to the final certification of arms, communicated family alliances through marriage, lineage antiquity, royal favor, and implied wealth.

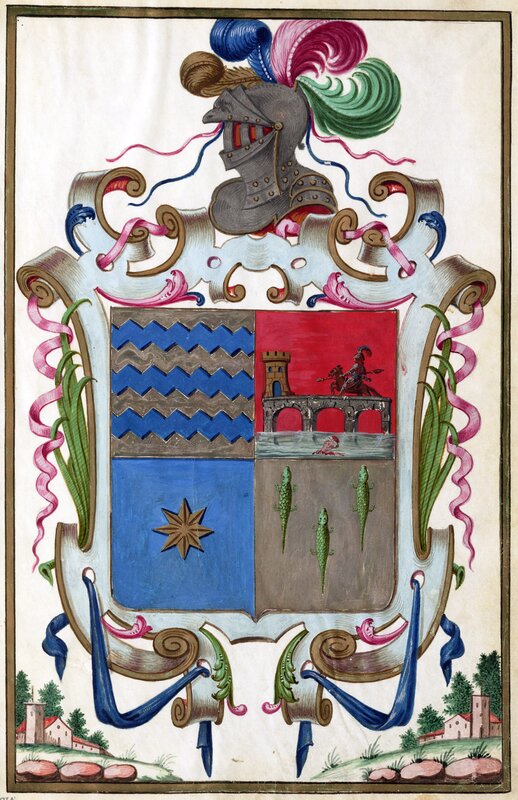

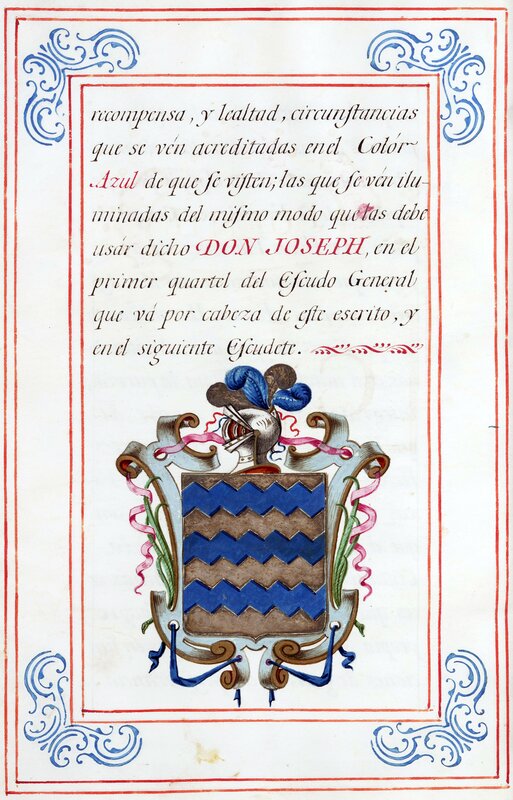

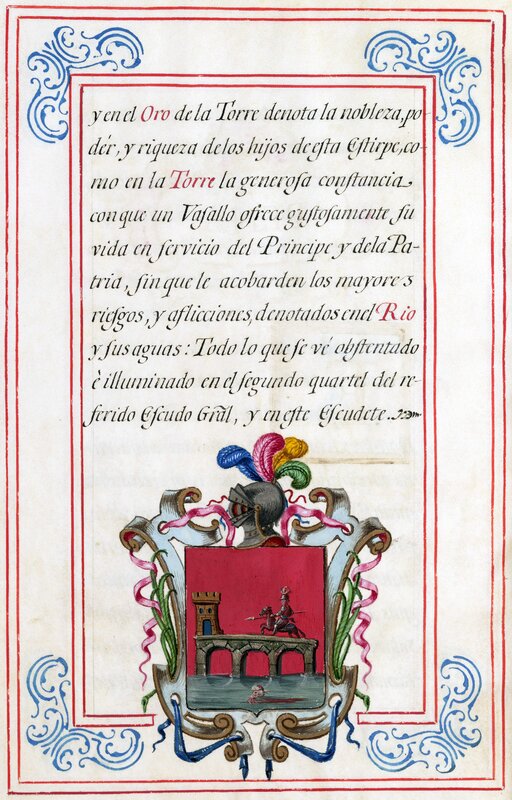

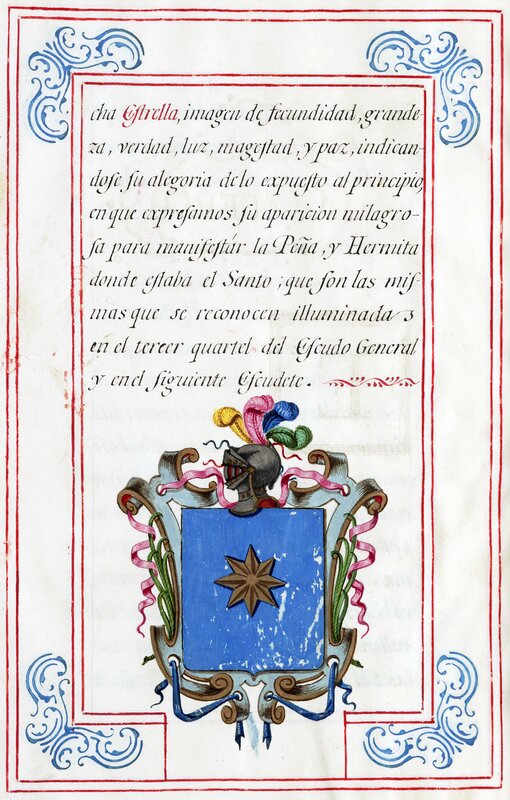

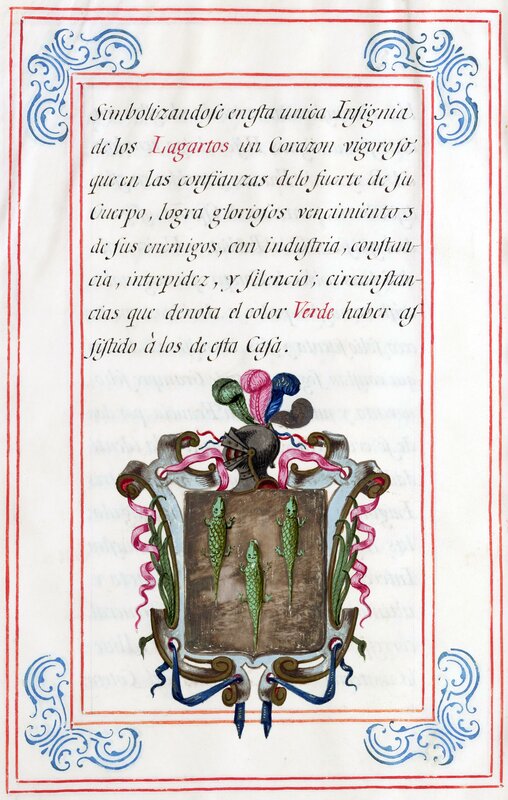

Coats-of-arms represented these complex genealogies succinctly. Tinctures, or colors, figurative representations, and the overall composition of each quadrant symbolized the historical lineages that converged in the individual’s family tree. Coats-of-arms conveyed the crafting of an identity that would aid in the negotiation of power, privilege, and status in Spanish society.

While the shield’s interior pointed to the past, the exterior referenced the present. Insignia surrounding the frame represented the individual’s current service to the Spanish Crown, such as their ecclesiastical, political, or military ranks. With all its intricate pieces, the symbol-laden graphic not only communicated an individual’s identity, but also—and perhaps most importantly—a perception of their power in the highly competitive Spanish colonial society. Colonial elites deployed these heraldic designs in architecture, paintings, books, and other objects to make their royally-recognized honor and power publicly known in New Spain and beyond.

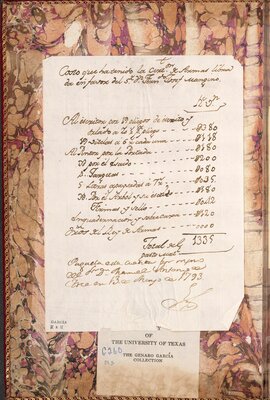

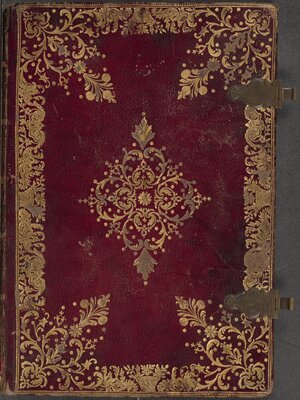

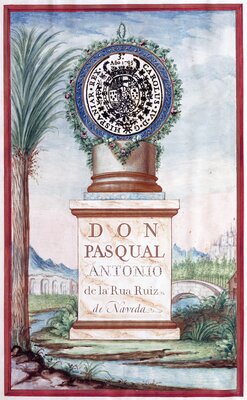

In the eighteenth century, artisans would regularly create presentation copies of Certifications of Arms. The invoice appended to Don Fernando Josef Mangino’s certification lists the various costs for the production of the bound documentation. Fees included the commission of a scribe with calligraphy skills to make a presentation copy of the legal records; an artist to design, draw, and illuminate the volume’s title page, coat-of-arms, initials, and genealogy tree; and a book binder who would add gold-tooled decoration to the covers and add metal clasps. Noble families treasured these bound, richly illustrated copies of their Certification of Arms.

Bibliography

Worldcat | Aldazábal y Murguía, Pedro José. Compendio heráldico: arte de escudos de armas segun el methodo más arreglado del blasón y autores españoles. Pamplona: Viuda de Martin Joseph de Rada, 1775.

UT Catalog | Lobato, Arturo R. “A General Survey of Heraldry.” Artes de México, no. 126 (January 1, 1970): 33–74.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Martínez, María Elena. Genealogical Fictions : Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2008.

UT Catalog | Torres, Mónica Domínguez. “Claiming Ancestry and Lordship: Heraldic Language and Indigenous Identity in Post‐Conquest Mexico.” Bulletin of Latin American Research, no. 30, 1 (March 2011): 70–86.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Twinam, Ann. Public Lives, Private Secrets : Gender, Honor, Sexuality, and Illegitimacy in Colonial Spanish America. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Resource | Zabala, Margarita. "Los Reyes de Armas en España." Hidalguía, no. 372 (2016): 483-554.