Marking the Landscape

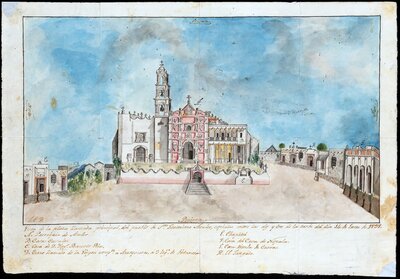

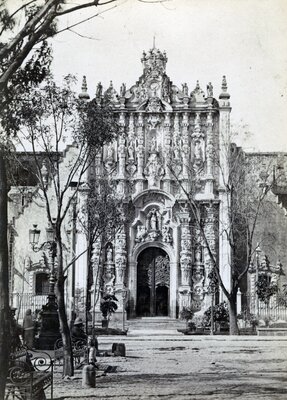

View of the convent and parish church of San Jerónimo Aculco by an unidentified artist, 1838. Established circa 1540, its facade is in the "Tetiqui" style, which was an Indigenous interpretation of sixteenth-century European architectural models.

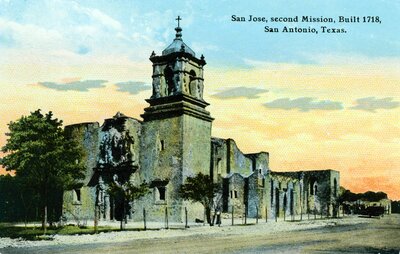

Architecture made the Spanish Empire visible in the Americas. Soon after the conquest in 1521, the invaders dismantled the Indigenous built environment to construct their own and assert power. Among these were the friars from the various religious orders who quickly established missions in the Valley of Mexico to acculturate Spain’s newest vassals. As the sixteenth century progressed, these “spiritual conquerors” continued to spread across the Mexican landscape, marking it with seemingly countless Catholic churches and convents. With the forceful congregation of Indigenous populations and additional Spanish settlement, many of these modest structures became the anchor for sprawling communities by the end of the sixteenth century.

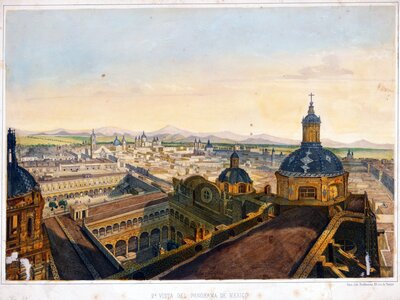

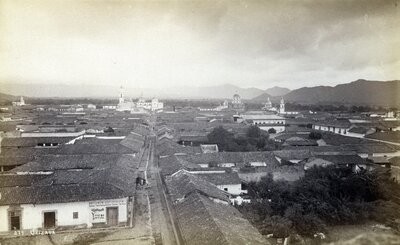

Colored lithograph showing a perspective view of south-east Mexico City from atop the Temple and Convent of Saint Augustine designed by Diego de Valverde and built 1677-1692.

As some of these missions and frontier towns emerged as district or regional seats, the Spanish elite started to finance the replacement of humble religious structures. While patrons offered funds as an act of piety and charity, they also sought to aggrandize their family name and honor by decorating architectural facades with their coats-of-arms. They commissioned architects locally and abroad to erect what would eventually become “colossal symbols of the colonial order.”

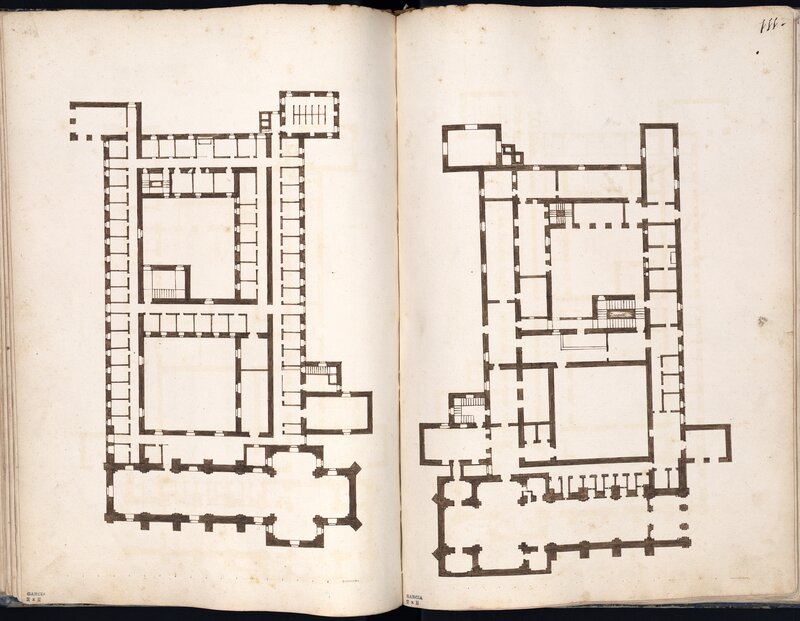

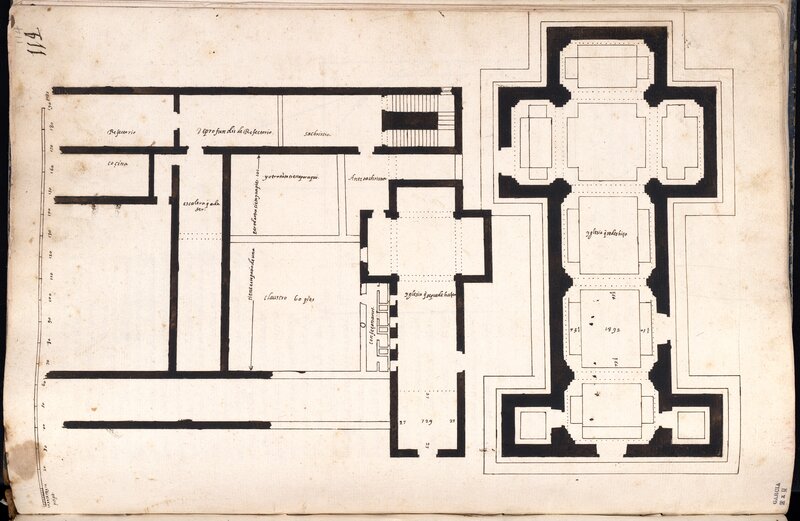

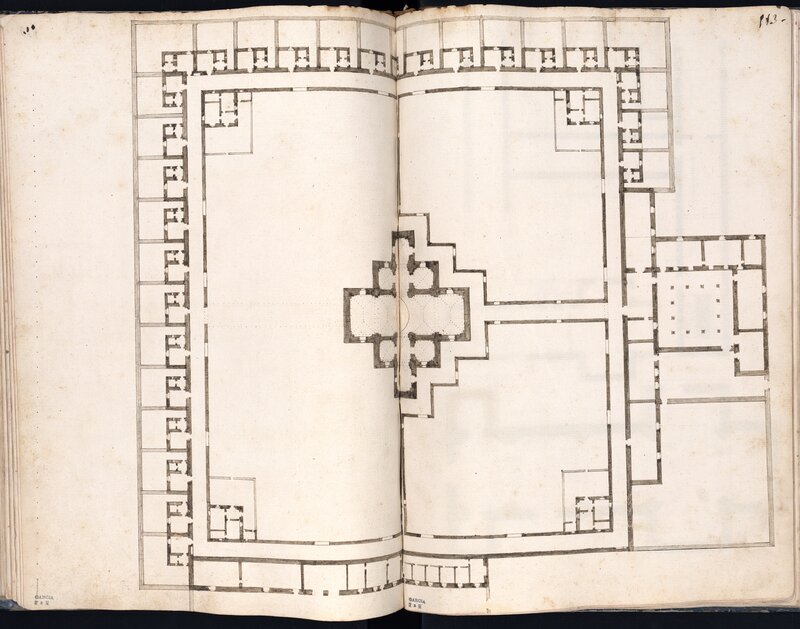

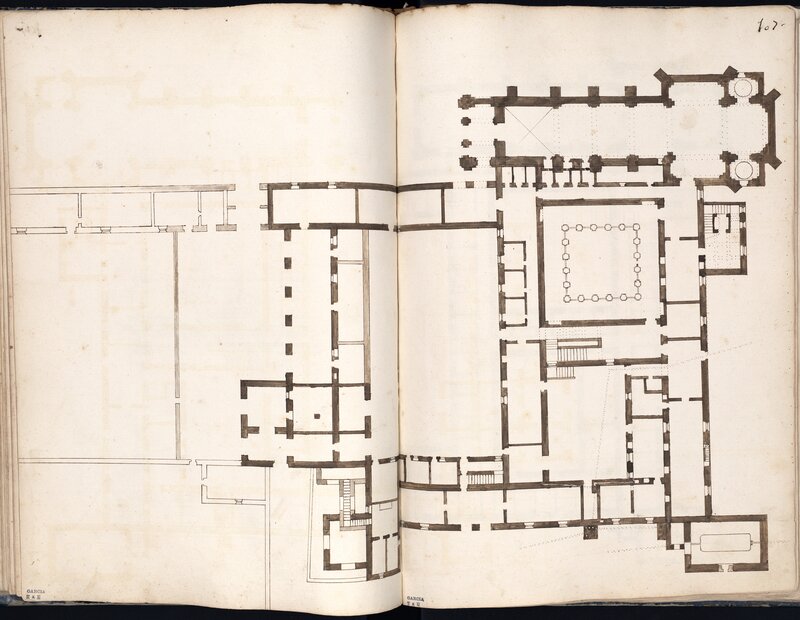

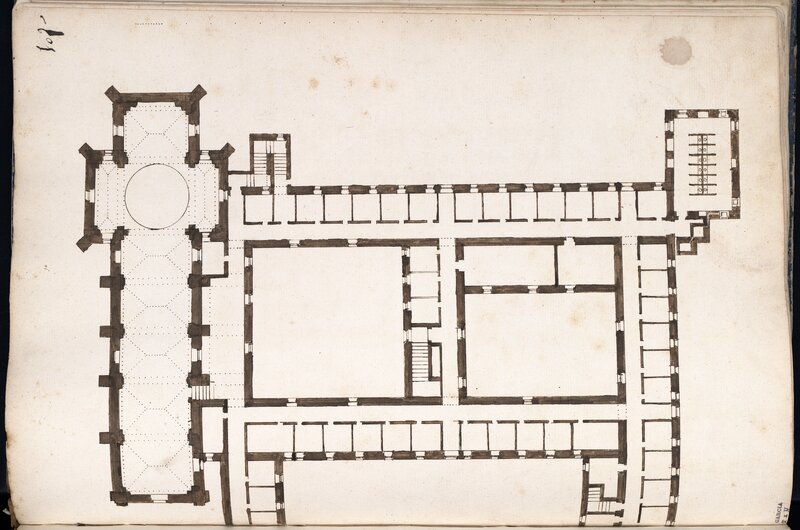

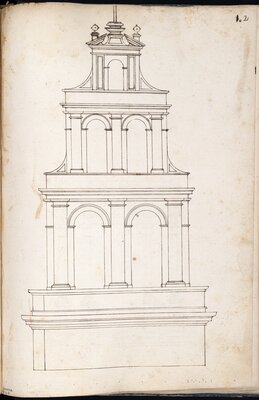

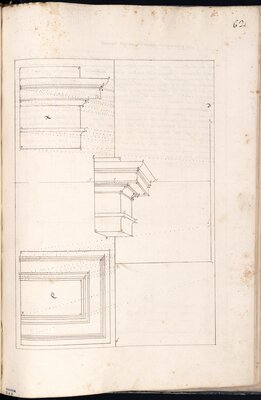

Among these designers was Friar Andrés de San Miguel. Soon after joining the Carmelite Order in 1600, he started contributing to the built landscape of power in New Spain. Throughout his life, he designed and led the construction of convents and churches in Querétaro, Celaya, Valladolid (present-day Morelos), Puebla, Atlixco, Salvatierra, and Mexico City. The floor plans below, one of which materialized, were part of a treatise the friar wrote at the end of his life with the intent to educate the next generation of architects.

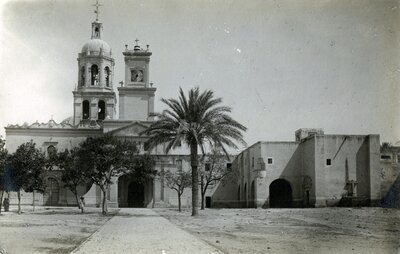

Around the same time, colonial authorities started to relocate the architectural focus away from these mendicant churches and convents. Recasting these structures as supportive actors in the urban theaters of Hispanicization, royal officials constructed municipal halls—or audiencia palaces if new administrative jurisdictions formed—around a new plaza. The formal secular Church, which was attempting to wrench back local religious authority from the mendicant orders, also began to erect its own monumental cathedrals and parishes around these reconceived city centers. Despite the visual representation of both colonizing forces at the center, the Catholic Church reigned supreme. Collectively, the domes, spires, and bell towers of countless colonial churches, temples, and shrines punctuated the architectural panorama of rural and urban New Spain.

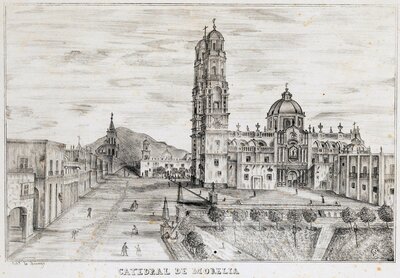

Lithograph perspective of the cathedral and plaza of Morelia, Michoacán (formerly Valladolid) by Arango, circa 1830-1850. So grand were these symbols of power that many of them did not celebrate their completion until the eighteenth century. Named as lead architect by New Spain's viceroy in 1658, Vicencio Barroso de la Escayola designed and led the construction of the imposing structure until his death in 1692. The structure took nearly a century (1660-1744) to complete.

New Spain’s architects referred to European models and principles to develop a unique and diverse architectural style, often piecing together Mannerist, Baroque, Neoclassical, Gothic, Renaissance, Mudejar elements in one structure. Geometry dominated: Novohispano designers considered the forms derived from mathematical application sacred, a common perspective during the Renaissance period. However, aesthetics changed through the centuries. For example, with the ascension of the Bourbon dynasty in 1700, French tastes and styles started influencing architectural design in New Spain.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008.