Financing an Empire

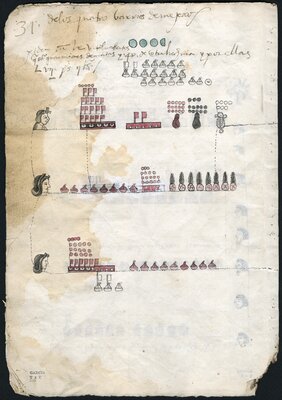

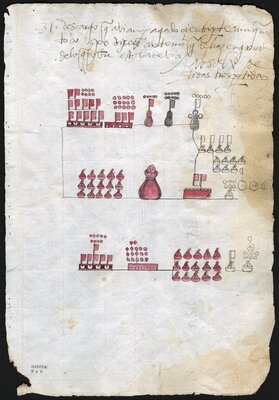

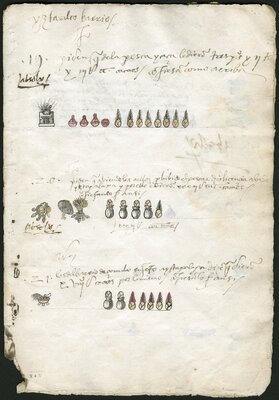

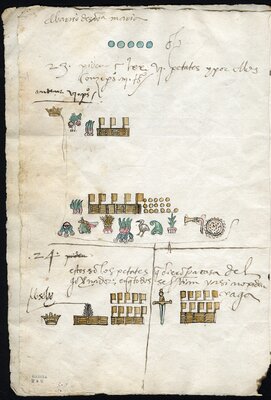

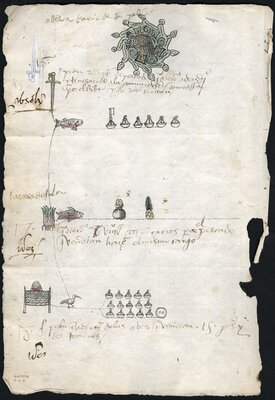

Tribute entries for Indigenous barrios, or neighborhoods, in and around Mexico City by an unidentified Indigenous scribe, circa 1550. The communities of Altlaca (San Pablos), Tula, Santa Maria, and Iztacalco paid tribute with birds, cacao beans, fish, game, and clothing adornments.

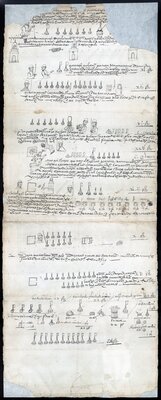

Tribute from the Indigenous communities funded New Spain's colonial power structures. They contributed foodstuffs, textiles, cacao beans, and animals to encomenderos and royal officials, who would then valuate the goods and affix a monetary value. As this payroll document demonstrates, local and regional administrators would claim their salaries from the tribute and channel the rest through the imperial apparatus.

The Catholic Church was not without sin in the colonial extraction. The institution required Spaniards and other non-Indigenous groups to pay tithes, a ten-percent tax on agricultural production, which sustained most of its operational costs and clerical salaries. Encomenderos, who had the responsibility of hiring a parish priest to look after the spiritual well-being of the Indigenous communities they oversaw, transferred the cost onto the Indigenous people by increasing their tribute levels (Schwaller, 19-23, 69). Communities who had friars as their local priests had to support them with food, goods, and labor since mendicants could not benefit from the tithe.

Throughout the sixteenth century and beyond, Indigenous people deftly navigated Spanish judicial systems to counter the exploitative extraction of resources. They had two recourses for justice, the first being the viceregal government. Soon after the conquest, Indigenous communities cultivated and forged a lord-vassal relationship with the "king's living image," the viceroy, that emphasized their need for protection against self-interest (Owensby, 10).

Indigenous people also resorted to ecclesiastical courts to redress Spanish abuses. In this document, a Native scribe listed the instances in which the Tepatepec community felt Mixquiahuala’s corregidor, the district’s royal administrator and judge, defrauded them. They alleged that Corregidor Manuel de Olvera—identified throughout the account with a staff—did not deliver on payment of goods and legal representation regarding tithes and labor conscription.

The Indigenous community appended this claim to a legal case brought forth in an ecclesiastical court by Mixquiahuala’s cleric Juan de Cabrera; the priest accused Olvera of preventing the region’s Natives from attending mass and paying him his salary. Tepatepec’s indigenous leaders saw this as an opportunity to seek possible retribution for monetary and property losses from Olvera, deploying the same discourse of "needing protection" the Spanish used to justify their dominion over them.

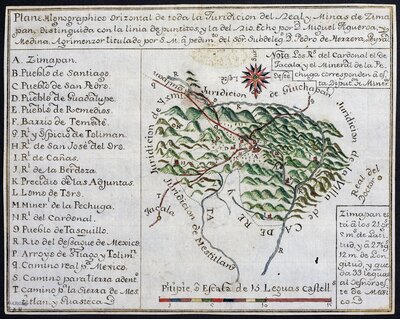

Map of the royal Zimapán mines (present-day Zimapán, Hidalgo, Mexico) by Miguel Figueroa y Medina, 1789. Miners extracted gold, lead, arsenic, sulfur, antimony, saltpeter, and ocher, among other metals, from various sites in the mountainous region. The mines were so important to the Crown that they received the designation of ‘royal’ ('Rl.') before their proper names.

The extraction of silver in the Americas more broadly sustained the Spanish empire, especially in the 18th century. Mine administrators depended heavily on enslaved African, afro-descendants, and Natives—who were drafted with royal permission by sacagentes, or press-gangs—to extract the mineral wealth. In the Zimapán mines, the workforce was drawn from over 700 Otomis and 35 afro-descendants in the region.

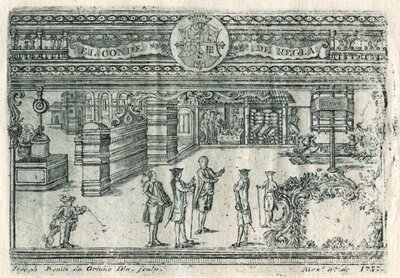

Mine workers did rebel against the conscription and subsequent abuses. Pedro Romero de Terreros, or the Count of Santa María de Regla, dealt with several strikes in his nearby Real del Monte-Pachuca mines a few years prior to purchasing the Zimapán Lomo de Toro mine in 1768, letter 'L' in the map above. He extracted from his numerous mines tin, silver, and magistral, which was used in silver refining. The count would eventually dominate the mining industry and the novohispano economy overall, becoming its wealthiest elite in the 1770s and making New Spain the empire’s richest territorial possession.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Boorstein Couturier, Edith. The Silver King: The Remarkable Life of the Count of Regla in Colonial Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Owensby, Brian Philip. Empire of Law and Indian Justice in Colonial Mexico. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2008.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Schwaller, John Frederick. Origins of Church Wealth in Mexico: Ecclesiastical Revenues and Church Finances, 1523-1600. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1985.

Additional Resources

UTEP Archival Collection: Acosta Solís Vargas family papers, MS560

UTEP Archival Collection: Ian Benton papers relating to Chihuahuan haciendas, MS126