Transoceanic Crusades

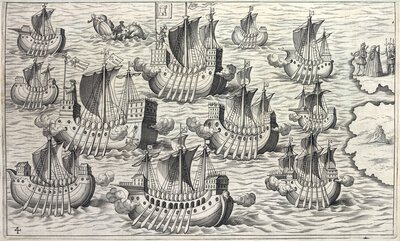

Engraved image of a Spanish Catholic flotilla leaving the Iberian Peninsula by an unidentified artist, 1621. A Catholic bishop holding the papal banner (crossed keys under the papal hat) seemingly leads the flotilla, which are mostly bearing the same standard. A conquistador holding Castile's banner (a castle tower) on the top-center galleon appears to follow the cleric, signifying that the voyage was a Christian crusade. Notice the Spanish Catholic monarchs, Ferdinand V and Isabella I, on the top-right bidding the ships farewell.

Europeans initially set their sights across the Atlantic Ocean in search for Asia's spice trade. Betting on the projections of an Italian explorer, Christopher Columbus, the Spanish Catholic monarchs, Ferdinand V and Isabella I, financed his expedition into uncharted waters in 1492. As the story goes, he would not find what he proposed. Instead of locating a sea passage to the East Indies, or lands in and around the Indian Ocean, Columbus encountered a whole "New World" of resources for the Europeans.

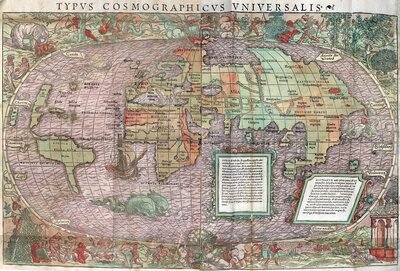

Based on the information Columbus and other European explorers and conquistadors relayed back, cartographers started to graphically invent the idea of what lied beyond the Atlantic Ocean. Slowly, the "Americas"—named after another Italian navigator, Amerigo Vespucci—started taking form in maps that emerged during the early sixteenth century. These imaginings served as instruments and symbols power: cartographic depictions of lands beyond the oceans enabled European sovereigns, or rulers, to stake out and represent "global" empires.

Colored map of of the world depicting an early understanding of the Americas to the left by an unidentified artist, 1537.

These cartographic images were a European "creative enterprise" that invented the idea of the "Indies", or lands across the Atlantic Ocean the Spanish Crown claimed (Padrón, 27-28). Despite the depiction of entire islands, continents, and oceans being part of the Spanish Empire, the reality was different. Royal representatives and Spanish vassals occupied key geographic nodes and claimed the transportation conduits, or "corridors of legal authority", that connected them to establish a network of spaces that would represent Spanish sovereignty. This resulted in an imperial "fabric that was full of holes, stitched together out of pieces, a tangle of strings" (Benton, 2).

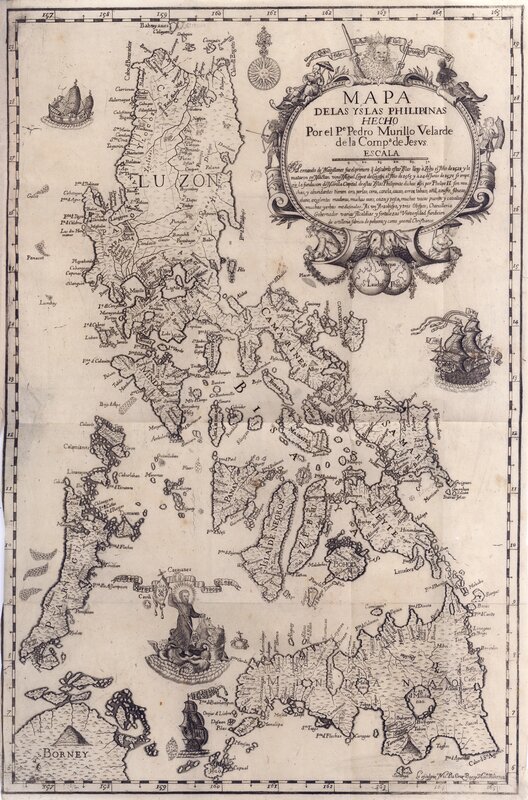

While oceans could never really belong to anyone, the lands that lied beyond them always could in sovereigns' minds. Coming full circle, the Spanish Crown finally managed to reach the East Indies trade when they crossed the Pacific Ocean and landed on what would be called the Philippines in 1565. Prior to Spanish domination, the archipelago already had strong economic relationships with China and other nation-states in the mainland and South Asia. Thus, it quickly became the nexus of trade between Spain and the Orient. To formally mark its presence, the Spanish established Manila in 1571 and made the Philippines the empire's bastion in Asia.

Besides influencing the Asian market, the Spanish Crown also sought to impart its culture and religion. By the 1540s, Jesuits, among them Saint Francis Xavier, had already established missions in Southeast Asia and Japan. Throughout the second half of the century, Catholic priests collected information about Asian spiritual beliefs and practices, such as Confucianism and ancestor worship, to devise proselytizing approaches. However, Christian ideologies and antagonism towards Japanese rulers and customs eventually led to their prosecution in the late 1560s. This came to a climax in 1597 when twenty-six Jesuit fathers, among them Philip of Jesus—who would be come the first novohispano saint—were martyred.

-

"Map of the Philippine Islands"

Map of the Philippines, indicating the names of the islands and their settlements, bays, ports, rivers, and lakes. Along the island coasts, the cartographer depicted sailing ships and Saint Francis Xavier on a chariot being pulled by seahorses and mermen. The frame around the map title depicts indigenous and Asian men and women with babies, umbrellas, bows, and shields. —— Mapa de las Filipinas, que indica los nombres de las islas y sus asentamientos, bahías, puertos, ríos y lagos. A lo largo de las costas de las islas, el cartógrafo representó buques y San Francisco Javier en un carro tirado por caballitos de mar y tritones. El marco alrededor del título del mapa muestra a hombres y mujeres indígenas y asiáticos con bebés, paraguas, arcos y escudos.

-

"Treatise...to prohibit Chinese Christians from doing certain ceremonies... in veneration of...

In three parts, the treatise discusses the structure and composition of the Mandarin language, the teachings of Confucius, and spiritual practices and customs related to the veneration of the ancestors. —— En tres partes, el tratado analiza la estructura y composición del idioma mandarín, las enseñanzas de Confucio y las prácticas y costumbres espirituales relacionadas con la veneración de los antepasados.

-

"San Felipe de Jesús Martyr of Japan and Patron of Mexico City, his Homeland"

Illustration of Philip of Jesus tied at the cross and pierced with spears. Vignettes of his journey to and martyrdom in Japan are on each corner of the composition. —— Ilustración de Felipe de Jesús atado a la cruz y atravesado con lanzas. En cada esquina de la composición hay viñetas de su viaje y martirio en Japón.

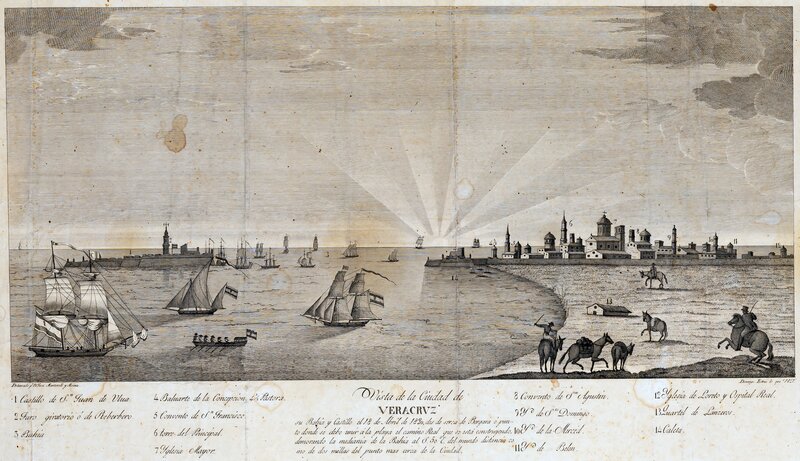

Connecting the metropole to its far-flung territories, New Spain's ports were perhaps the most guarded nodes in the imperial network. The Spanish Crown channeled licensed transoceanic trade through these coastal towns to maintain a firm grasp on the economy, especially its revenues. Annually, American silver exited the continent through novohispano ports to fuel global economies and wars in Asia and Europe. In the Pacific Coast, Acapulco equipped the Manila Galleon with silver destined to the Philippines and beyond to bring back Chinese goods, such as silk, spices, and porcelain. On the opposite coast, Veracruz sent silver across the Atlantic to refill the Spanish Empire's coffers.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Benton, Lauren A. A Search for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400--1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Flynn, Dennis O, Arturo Giráldez, James Sobredo, Dennis O Flynn, and Arturo Giraldez. European Entry into the Pacific: Spain and the Acapulco-Manila Galleons. 1st ed. Vol. 4. Florence: Routledge, 2001.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Padrón, Ricardo. The Spacious Word : Cartography, Literature, and Empire in Early Modern Spain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.