Spiritual Conquest

Map of Guaxtepec by an unidentified Indigenous artist, 1580. Central to the composition is the village's St. Dominic convent and church. The painter placed the building just above the Indigenous community's logograph, which comprises a huaxin, or Mexican calabash tree, on a hill.

Catholic priests came at the heels of the European invaders to start the religious conversion of the Indigenous. The first clerics to arrive in Mexico belonged to the Catholic religious orders, which were spiritual fraternities governed by specific rules, such as the Franciscan, Dominican, and Augustinian Order. Members of these communities took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience and initially lived a life of seclusion for religious contemplation. However, the Spanish colonial enterprise soon thrusted some of these mendicants into the "New World".

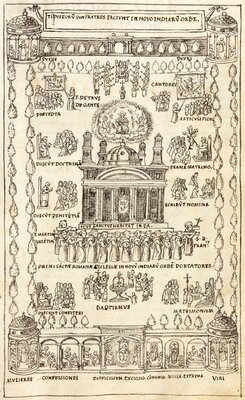

The Catholic Church and the Spanish Crown tasked the mendicant friars-turned-missionaries with the Hispanicization of the Indigenous. The primary challenge was in translating Christian concepts and beliefs. Initially, the friars communicated with images that illustrated biblical stories and dogma, along the lines of what this hand-drawn scene depicts: At the bottom of the composition, a Franciscan friar uses a stick to point at elements of the crucifixion scene in the background to teach the Indigenous catechumens sitting before him.

Missionaries typically divided families in their conversion activities to "conquer" souls. Friars segregated adults from children and women from men when they preached and administered Catholic sacraments, or religious ceremonies imparting spiritual grace onto individuals. Upending parent-child relationships, the priests made boys into altar assistants and encouraged children to tell on their parents if they witnessed "idolatrous" behavior at home.

This diagram demonstrates the spiritual work missionaries did in New Spain among the Indigenous. Foremost was catechism, or the teaching of Christian doctrine, as seen in the top-left corner of this illustration: Franciscan Fr. Pedro de Gante points at images to communicate Christian concepts. It also depicts the missionaries' administration of sacramental rites, including baptism, communion, confession, penance, and matrimony. This last ritual was perhaps the most damaging cultural change friars implemented; Christianity imposed monogamy on a polygamous culture, destroying established marriage and hereditary lines.

Through these ceremonies and rituals, the friars were also instituting Western European concepts of time. The sacramental rites set a Christian life course on the Indigenous that started with baptism soon after birth and ended with extreme unction, or the last rites. They also imposed on them the yearly Christian calendar through public feasts during saints' days.

Missionaries also attempted to regulate the daily lives of catechumens. They hung a bell at the highest point of their conventual churches, which were centrally located, so that its toll could be heard across the town and its vicinity. For example, the Augustinians at Quatlatlauca erected a bell tower as seen in this map. Throughout the day, the friars and their assistants rung it to signal the hours of the day and enforce a Western European schedule.

Indigenous groups did not always comply with the mandates of the religious colonizers. Some communities found parallels between the Christian and Nahua belief system and practiced the latter under the guise of the former. Other groups, such as those in the northern frontiers of central Mexico, vehemently rebuffed missionaries well into the seventeenth century.

The illustrations framing this vow of profession to the Order of St. Augustin reference the perceived danger of missionary work. Among the depictions of mythical, devil-like creatures and nude figures, there is a scene at the top-right corner of presumably an Indigenous person hanging a friar. At the bottom of the frame, another scene shows two friars kneeling towards angels holding a burning heart—the Augustinian emblem—as two arrows whirl towards them, with Jesus Christ and Saint Augustine witnessing the event from either corner.

However, the threat and potential martyrdom did not deter religiously inclined men from joining the mendicant orders to partake in the colonial enterprise. The map below indicates the birthplaces of friars admitted to the Augustinian Order in New Spain's convents during the 16th century. To learn more about this religious order, visit The Augustinian Order in Sixteenth-Century Mexico digital project.

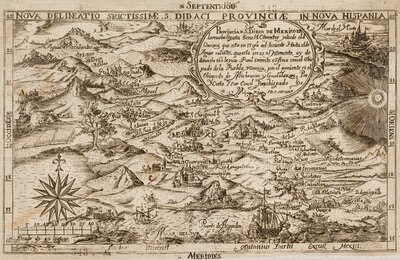

Throughout the sixteenth century, the religious orders grew and started to establish convents throughout New Spain. As they spread, they started to carve out provinces (administrative territories) with head convents in major urban centers such as Mexico City, Oaxaca, and Valladolid (present-day Morelia, Michoacan). The map below delineates the Discalced Franciscan Province of San Diego of Mexico in 1682, which at that time contained fourteen convents across the region between Aguascalientes and Oaxaca.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Melvin, Karen. Building Colonial Cities of God: Mendicant Orders and Urban Culture in New Spain. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2012.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Mundy, Barbara E. The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Wade, Maria de Fátima. Missions, Missionaries, and Native Americans: Long-Term Processes and Daily Practices. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008.

Additional Resources